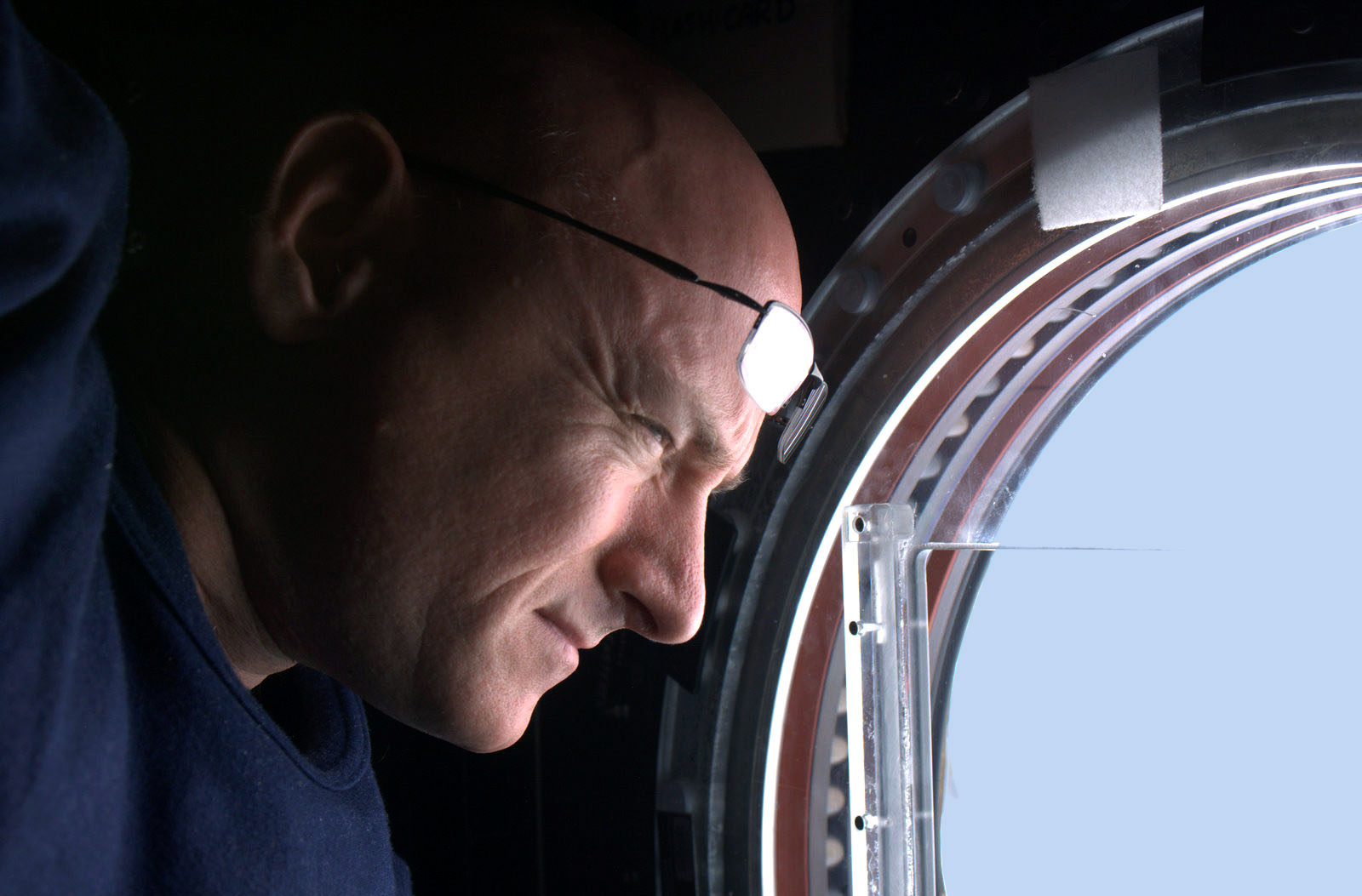

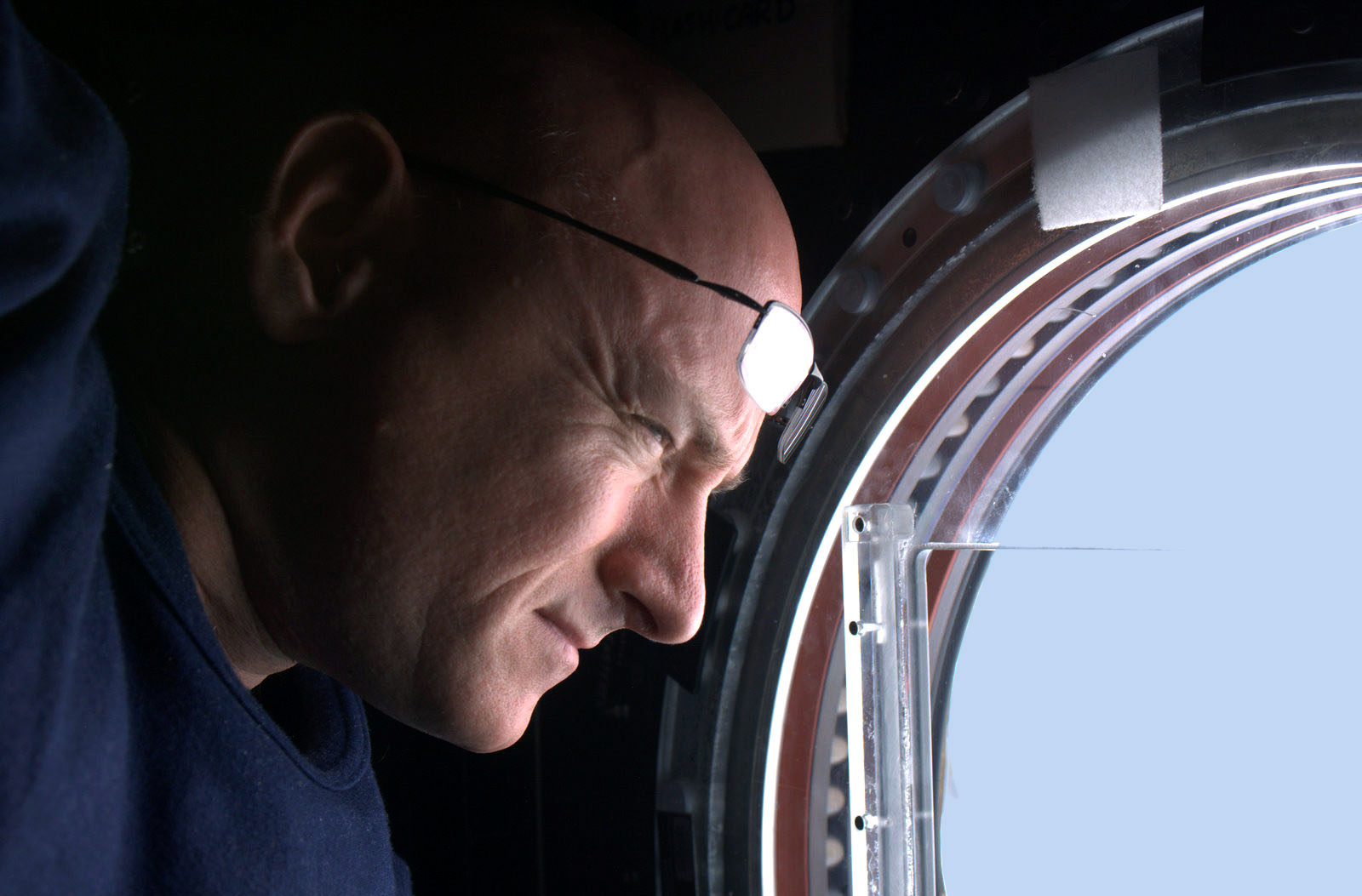

This afternoon, astronaut Scott Kelly will say goodbye to the International Space Station. It’s a smelly tin can in low Earth orbit, but it’s been Kelly’s home for 340 days.

To help NASA predict how going to Mars will affect human health, Kelly lived on the ISS for just shy of an entire year–double the length of a normal space station stay. He and his twin brother, Mark, who remained back on Earth, have been subjecting themselves to blood tests and other measurements to determine how long-term spaceflight alters the immune system, microbiome, mental health, and more.

Although Kelly will return to Earth this week, NASA’s “Year In Space” isn’t over quite yet.

Testing

Almost as soon as Scott Kelly gets out of the Soyuz capsule, he and his Russian counterpart, Mikhail Kornienko, will be submitted to a slew of tests.

“They’ll be going through a variety of different tasks that look a lot like what you might have to do if you had just landed on the surface of Mars,” said International Space Station Chief Scientist Julie Robinson in a NASA video. Like going through an obstacle course, they’ll try climbing ladders, opening hatches, connecting valves and tubing, and getting back up after falling–tasks that are relatively easy for most of us, but which can be tough after you’ve been living in microgravity for a year.

During these tests, Kelly will be wearing motion sensors on his arms, legs, and chest, says Stevan Gilmore, the lead flight surgeon on the mission. The motion sensors help measure how well Kelly can perform the tasks compared to before he left Earth. They’ll also be comparing his performance to that of past astronauts.

Over the course of Kelly’s mission, NASA has been testing techniques to try to combat some of the health risks of living in space. For example, in space, the body fluids seem to concentrate in the upper body, which not only causes a permanently stuffy nose, but could be related to the vision problems that some astronauts develop. During Scott Kelly’s mission, the team has been testing Chibis–basically a pair of vacuum pants meant to suck the fluids down into the legs.

Similarly, NASA’s ARED device is an exercise machine that simulates the resistance of gravity with the intent of helping astronauts combat muscle loss.

Once the astronauts get back on the ground, their performance in the landing tests will reveal whether countermeasures such as these helped, and/or would be useful during a trip to Mars.

More testing

In the first few days after landing, NASA doctors and scientists will need to take more samples from the Kelly twins. Then there will be more data collection at 30 days, 45 days, 60 days, and up to 9 months out for some genetic tests. Plus, many of the biological samples taken Scott Kelly on the space station are still up there, waiting for the next SpaceX capsule to carry them to Earth in April.

John Charles, the chief scientist of NASA’s Human Research Program, says he expects the bulk of the study results to be published about a year from now.

Other tests could go further out than 9 months. NASA scientists will probably want to review the twins’ annual physical exams and bone loss measurements, the latter of which can go out for several years.

“If they lost bone, it can take up to three years to recover,” says Robinson.

Rehabilitation, and more testing

After the Soyuz capsule lands in Kazakhstan, Scott Kelly and his doctors will get on a 20-hour flight to Houston. After that is when the reconditioning begins. The space station exposes astronauts to gravity that’s 10 percent weaker than that of Earth, and despite exercising for a few hours a day, Kelly will likely have lost some muscle mass.

Astronauts coming back from a six-month stay on the ISS usually get rehab, with daily workouts and targeted exercises, for 45 days. And even though Kelly has been up there for twice as long, lead flight surgeon Stevan Gilmore thinks he’ll require the same 45 days to readjust to life back on Earth.