On August 25, Senator John McCain died after a year undergoing treatment for glioblastoma (GBM), a particularly aggressive brain cancer.

But what exactly is this type of cancer, and why is it so deadly? A report by Roche estimates that there are around 240,000 cases of brain and nervous system tumors diagnosed worldwide per year, with GBM being the most common and the most lethal. Even in recent American history, it has claimed the lives of both Senator Edward Kennedy and Beau Biden, son of former Vice President Joe Biden.

Where do these cancers come from?

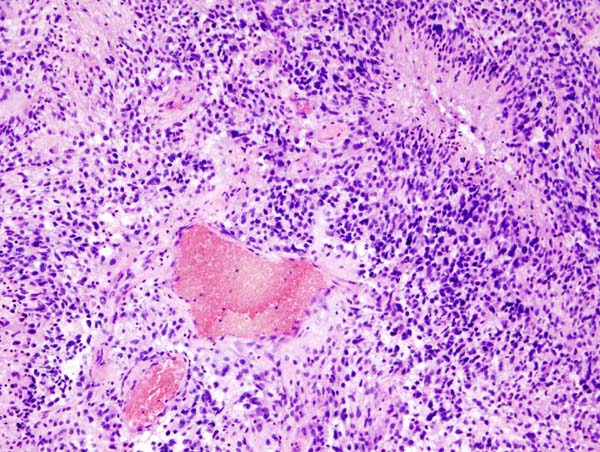

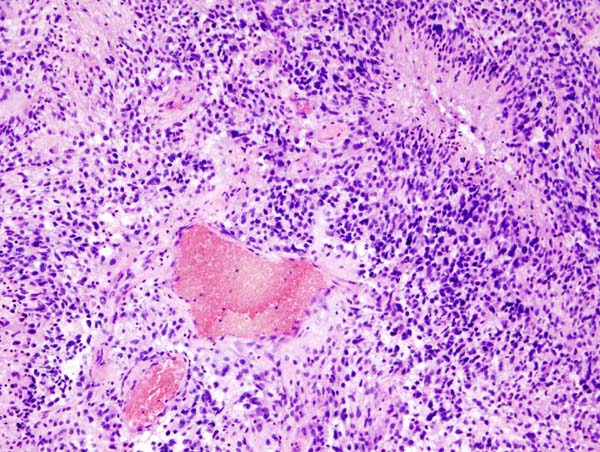

GBM is a very aggressive form, or a Grade IV, type of brain tumor called an astrocytoma. It’s a type of glioma, a brain tumor that begins in the glial cells that surround and support neurons.

“Specifically, it forms in malignant or cancerous astrocytes, which are the star-shaped support cells of the brain,” says Barbara O’Brien, an assistant professor at the University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center. “These cancerous cells multiply, and as they create more and more mass, the pressure in the brain may cause the patient symptoms.”

Those can include anything from general neurologic symptoms, like headaches or seizures, to symptoms that stem from specific areas of the brain, like speech difficulty, weakness on one side of the body, or double vision.

“The symptoms in some patients improve with treatment, and the symptoms may worsen, or new symptoms may develop, if the tumor begins to grow,” O’Brien says.

Who is affected by GBM?

O’Brien estimates that there are around 2 or 3 cases of GBM for every 100,000 people in America. It is the most common form of primary brain tumor (a cancer that begins in brain tissue) and in most cases it does not spread to any part of the body.

There aren’t really any known risk factors, except for that it’s mostly found in people in their fifties, sixties, and older, and it’s slightly more common in men. Very rarely, it can be seen hereditarily in people with certain genetic syndromes such as neurofibromatosis type 1, Turcot syndrome, and Li Fraumeni syndrome.

“Hair dye, living near power plants, manufacturing, cell phones: all of this has been investigated, but none have been identified as risk factors,” O’Brien says.

What happens if you have GBM?

GBM is typically diagnosed through brain imagery and then surgery. O’Brien says that if a patient experiences symptoms of a brain tumor, it’s necessary to see a physician to get the ball rolling on diagnosis through imaging.

“If the brain imaging, such as an MRI, does show or is suspicious for glioblastoma, the next step is for surgery,” she says. “After the surgeon removes the tumor tissue, a pathologist evaluates it and confirms the diagnosis for glioblastoma.”

Treatment includes removing as much of the tumor as possible, and then beginning radiation and chemotherapy. As of right now, O’Brien says, there is no definitive cure for this type of tumor. So doctors focus on maintaining the patient’s quality of life by keeping the mass from growing.

O’Brien says that the term remission isn’t used for GBM, and that the average survival rate post-diagnosis is less than two years. However, a 2009 study showed that around 11 percent of the subjects treated with radiotherapy along with temozolomide survived for five years.

Is there hope for future patients?

With more research, perhaps.

“We need better treatments for glioblastoma. The research is focused on just that: treatment,” O’Brien says. “One area of excitement is immunotherapy: using therapies to ramp up a patient’s own immune system to fight the cancer. This approach has been very successful in other cancers, such as melanoma, even in lung cancer.”

O’Brien says that there are a variety of other potential solutions being explored, like vaccines, viruses, and therapies called checkpoint inhibitors.

“So we are still in the early stages of investigating these techniques, and they are investigated in the form of clinical trials, and before a clinical trial is even established, these approaches are tested in the lab,” she says. “We still have a lot to learn, but these are some of the therapies that we are hopeful about.”

Update: A version of this article was previously published on July 20, 2017. It has been updated. Correction: Due to a typo, a previous version of this post misstated the rate of glioblastomas in the U.S. We regret the error.