Humans have a bad habit of leaving a trace wherever they go. The moon is no exception. Sure, we left some ceremonial flags held aloft by wire in lieu of a brisk wind to blow them, but the most telling things we’ve left aren’t what you see in commemorative photos.

The official NASA Catalogue of Manmade Material on the Moon lists 796 items, 765 of which are from American missions. Some as small as a pair of nail clippers, others consist of entire lunar rovers and probes that long ago crashed into the surface. We’re not totally sure where all these items are, but they’re definitely up there, cluttering the otherwise barren lunar landscape.

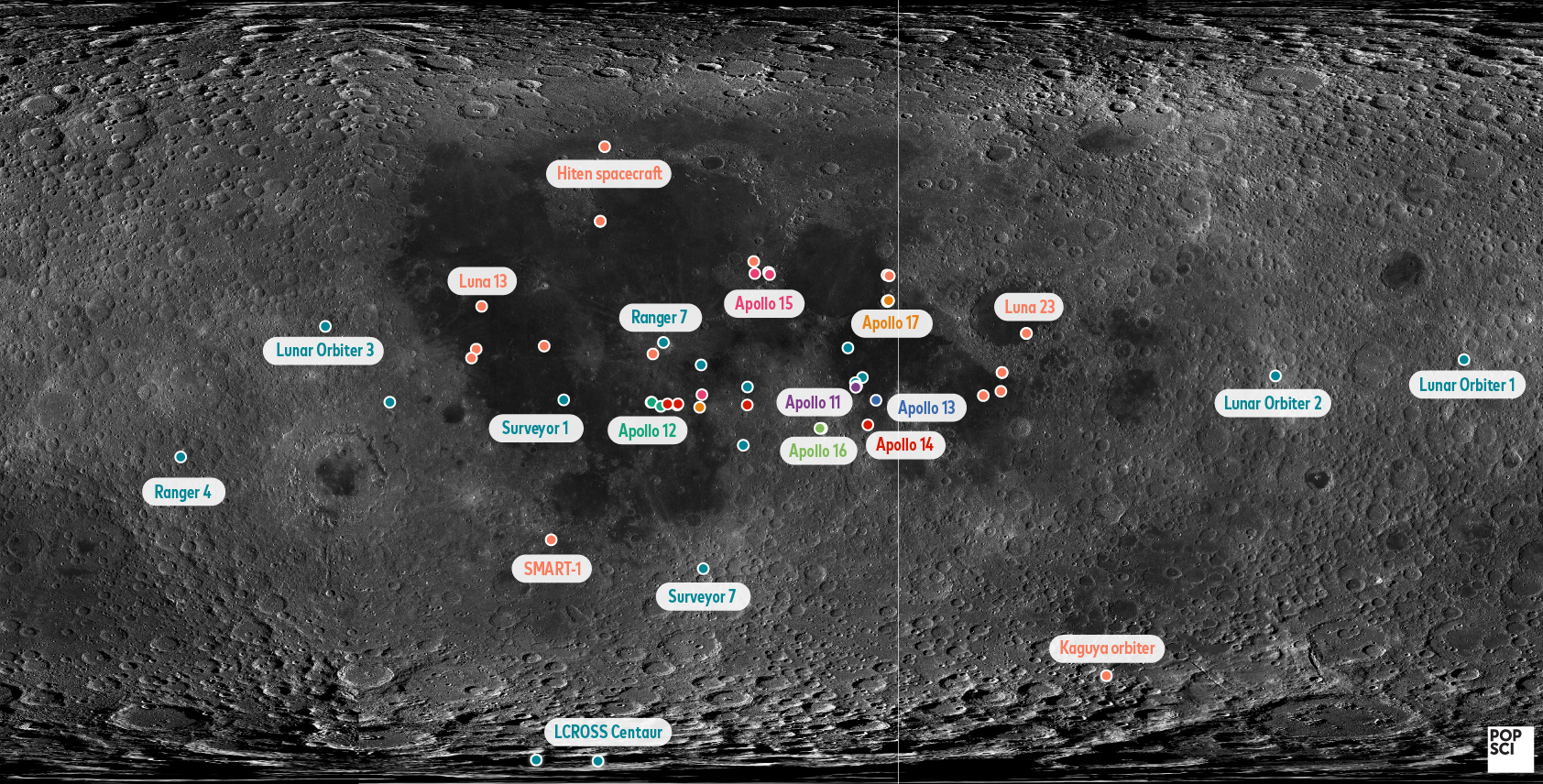

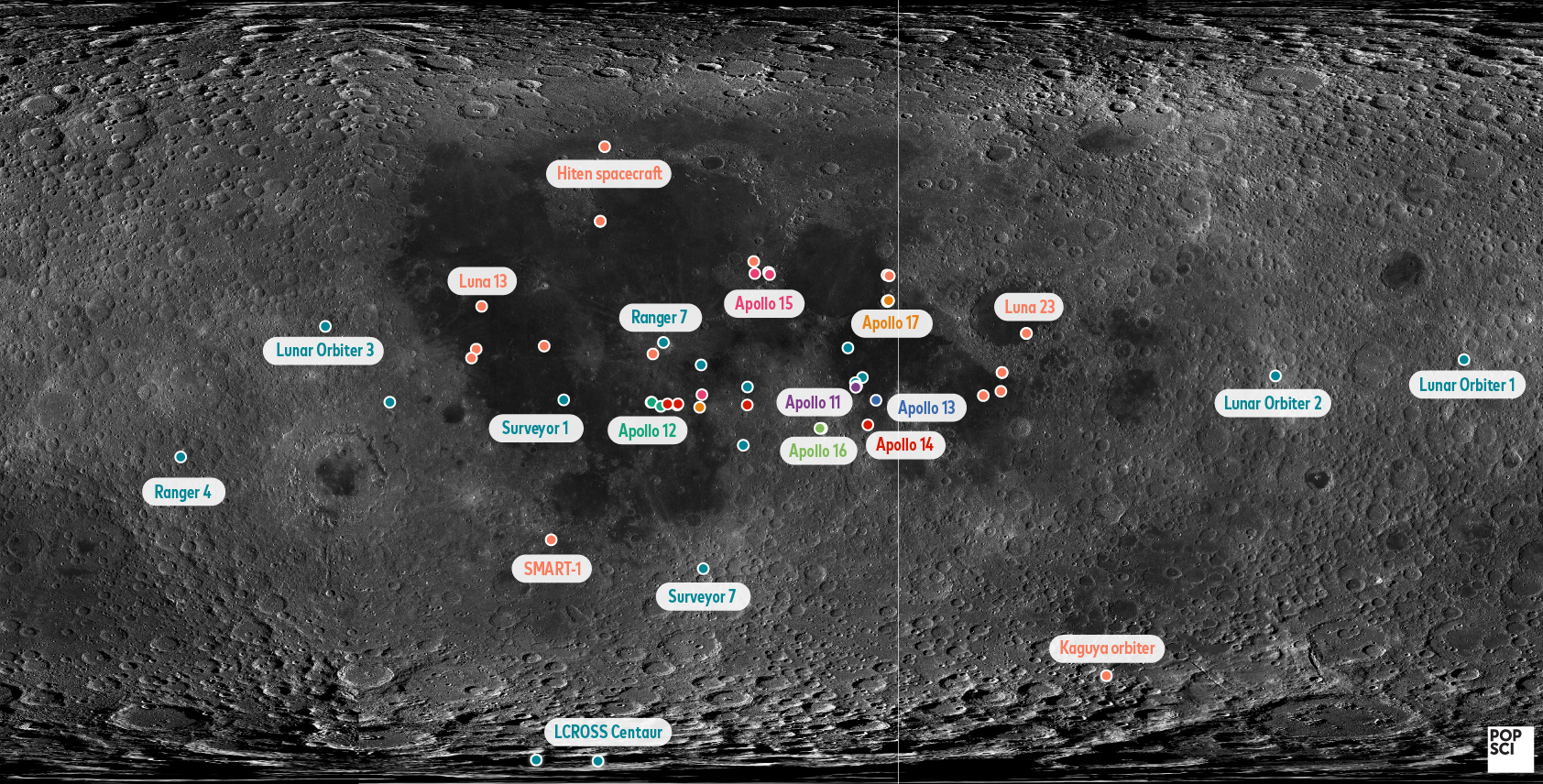

Yet somehow maps of the artifacts left on the moon never look that cluttered.

Most of the dots you can see are fairly large items. The Ranger spacecraft, for instance, were a series of uncrewed missions in the 1960s to get images of the moon. Not all of them made it (Ranger 3 missed the surface entirely), but 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9 all crashed into the surface. Similarly the Lunar Orbiters, well, orbited. They took photos in part to scope out potential landing sites for the first crewed missions, then came tumbling down once they were done.

The Surveyor program was actually designed to land on the moon. The craft launched in the late ’60s and demonstrated that we could make a soft landing, which would be crucial for the Apollo missions, plus started gathering some data about the lunar landscape.

Those dots near the southern pole are the LCROSS components. LCROSS, or Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, was a robotic craft sent in 2009 to explore the water ice present at the poles. One part of LCROSS, the Centaur stage, intentionally slammed into the surface to create a giant plume of dust so that the Shepherding stage could fly through and collect data to send back to Earth. The data they sent back confirmed the presence of water. Both are still sitting in their own craters near the moon’s south pole.

But far more interesting, at least from a human perspective, are all the other artifacts left in the lunar dust. The crewed Apollo missions only made six landings, but left a trove of trash.

The trouble with many maps of these artifacts—the above map included—is that most of the hundreds of bits and bobs have no specific known location. If you want to map them, you have to give them some default position (in this instance, we assigned them the landing location for their respective Apollo mission). But then all the dots overlap, and you can’t really appreciate just how much stuff there is.

So we expanded them all.

Each dot on these maps represents one item, and they’re not to scale—the landing coordinates are at the center of each array, and the dots certainly take up more space on the lunar backdrop than they should. But it will at least give you a sense of just how much we’ve left behind.

Many if not most of the artifacts were common to all the missions. They nearly all left behind Portable Life Support Systems, which kept astronauts alive inside their spacesuits. Those PLSS’s also had batteries and remote controls and valves associated with them, which all count as separate items in the NASA catalogue. Then there are the cameras, both still and video, used to transmit images back to Earth. And as any upscale camera owner knows, there are many lenses, cables, mounts, triggers, and handles to go along with each device.

Each of the missions also took samples and performed scientific experiments on the surface. That means there are assorted magnetometers, seismic experiments, suprathermal ion detectors, and so on that stayed behind while the data they collected returned home.

And then there’s all the bodily excreta. Though the astronauts often tried their best not to poop or pee much on their journeys, some of them had to go, and they did so in various defecation collection devices and urine collection assemblies. And for emergencies, there were also emesis bags, which we wrote down in the colloquial: vomit bags.

Not all of these little items are just sitting out on the surface. Many of them are probably inside the various spacecraft modules left behind for the sake of having a lighter take-off from the moon.

Here’s a close-up shot of each of the Apollo landing sites showing some of the artifacts still up there.

Some of these are pretty straightforward. Hammers are useful everywhere, even on the moon, and lifelines are pretty handy in low gravity. Others, like the memorial disc and gold olive branch, are obvious when you consider how sentimental humans are. There’s even a plaque on the lunar module descent stage.

The laser range reflector is less clear, but oddly is one of the items that’s not trash—we’re still using it today. Apollo 11, 14, and 15 each brought up one of these special mirrors designed to reflect an incoming laser beam directly back at its source. That means here on Earth, astronomers can point a laser at the mirror (with the aid of high-powered telescopes) and measure the distance to the moon to within three centimeters. These mirrors help us understand the moon’s orbit and how it’s changing over time (it’s getting farther away from us by about 3.8 centimeters a year).

Apollo 12 was a little less wacky—most of the equipment left behind was fairly standard, apart from the earplugs which only appear on this mission (though reportedly the crew snuck in some funny pranks during their time, the evidence isn’t listed in the official catalogue of artifacts). It’s unclear exactly what the lunar module utility towels were for, but the NASA catalogue notes that they came in red and blue.

The color chart is likely referring to the color/shadow chart that astronauts included in photos, much like you might hold up a piece of white paper to ensure you can properly white balance the picture later (you can see one in this photo). You need some kind of reference point within the image—like something entirely black or entirely white—so that when you’re processing the photo, you get the colors right. This is especially crucial on the moon, because all the cameras the astronauts took were designed on Earth for Earthly light. Whatever showed up on the film might look very different because of the different conditions in a vacuum. Some scientists even argued at the time that the Apollo missions shouldn’t have taken color cameras at all, because they thought the resulting images would be too unreliable. Photographers who have worked with images from the moon have said that the variation in hue is huge—some photos are strangely blue, others magenta, even though astronauts report seeing nothing of the sort.

Less scientifically, astronaut Al Bean also left his aviator wings on the surface alongside those of Clifton Curtis “C.C.” Williams, who was going to be the Lunar Module pilot for the mission. He died when his T-38 jet had a mechanical malfunction on his way to visit his father, who was dying of cancer. Bean took over that role after Williams’ death. He is also honored on the Apollo 12 patch, which has four stars to include the three-man crew plus Williams.

There are no electrical outlets on the moon, so to power some of the bigger experimental gadgets the astronauts needed, all the Apollo missions brought along a radioisotope thermal generator fueled by plutonium.

Other gadgets are more straightforward. Extension tools (along with tongs and other grabbers) helped astronauts grip and reach things that were challenging to hold in their puffy gloves. They also had in-suit drinking devices, since you can’t just sip a water bottle in the vacuum of space.

Unfortunately, there weren’t hammocks stretch out on the lunar surface like an otherworldly beach resort. The hammocks left on the moon were intended for use inside the spacecraft—they were where the astronauts could rest at the end of their eight-hour day of work. You can see an extremely tense-looking astronaut lying in one in this Apollo diagram.

As for the golf balls, you’ve probably seen the famous images of Alan Shepard hitting them in the moon’s low gravity environment. Even astronauts need to have fun. The javelin is somewhat more confusing. No one seems to have actually brought a true javelin to the moon, but Ed Mitchell did decide to throw the long handle from a sampling instrument like a javelin (you can sort of see it and a golf ball here), so our best guess is that the NASA archivists included this as a nod to the first and only lunar javelin toss.

Here’s where things get a little weird. We’ve got some standard stuff here—microfilm, inflight coverall garment (ICG) trousers (like these), and a lunar sampling rake. The liquid cooled garment is the layer astronauts wore beneath the marshmallow spacesuits, which had small tubes full of water running through them designed to cool the body. Even the U.S. Marine Corps flag and the wet wipes are pretty understandable (it’s TBD whether they’re still wet). The sleeping restraints are, of course, for sleeping in zero gravity, and the hammer and feather were part of a famous experiment demonstrating how, without air resistance, the two objects with different mass will fall at the same rate.

We have James Irwin to thank for a lot of the other strange items here. The bible is his, left on the dashboard of the lunar module, as is the portrait of himself—it’s a self-portrait, though there’s little to no information available as to what kind of self-portrait it is or why he brought it. He was also in on the plan to stash $2 bills in his personal preference kit (the small box of items you’re allowed to bring as an astronaut that’s not pre-assigned by NASA) in order to later sell them as moon memorabilia. Some of those $2 bills are available to purchase today, but the vast majority still reside on the moon—Irwin and his compatriots forgot them there.

We’re mostly back to normal here. Cosmic ray detectors and far ultraviolet cameras were just two of the many devices that Apollo 16 astronauts used to collect data on their lunar stay. Like so many before them, they also left a commemorative Air Force medal.

They also left behind the lunar roving vehicle, used to travel longer distances than they could easily walk to gather samples from more distant sites. The scoop, of course, was used to get those samples and presumably the map holder was for holding your map in your stumpy spacesuit gloves. Charles Duke also famously left a family photo, encased in protective plastic so that the lunar dust didn’t damage it. As for the tissue dispenser, it’s unclear why only Apollo 16 and 17 seem to have required one, but perhaps all the to-go packs at NASA were taken.

On top of some standard gear and assorted experiments, plus the obligatory roving vehicle, the Apollo 17 astronauts seem to have left a smattering of other personal items behind. The wrist mirror, while perhaps not so useful on Earth, was a handy tool on the moon. You could use it to redirect sunlight into dark spots, like a truly solar-powered flashlight.

Judging by the soap, anti-bacterial ointment, and personal hygiene kit left behind, they were at least a clean bunch. No word on why, for a 12-day journey, the astronauts required nail clippers—but we imagine there’s never been a harder cleanup job than gathering nail clippings in low gravity.