It’s been a hard month for space telescopes. First we learned that Kepler is running out of fuel, signaling the end of its second life as an exoplanet hunter. Then we got word that the much-anticipated James Webb Space Telescope faces yet another delay.

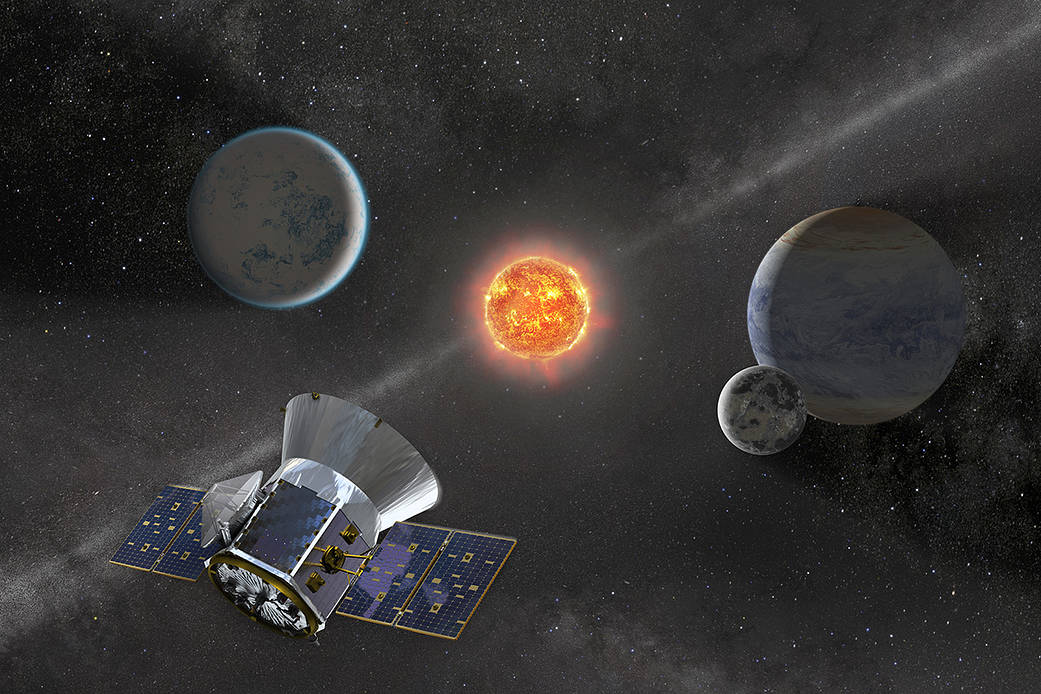

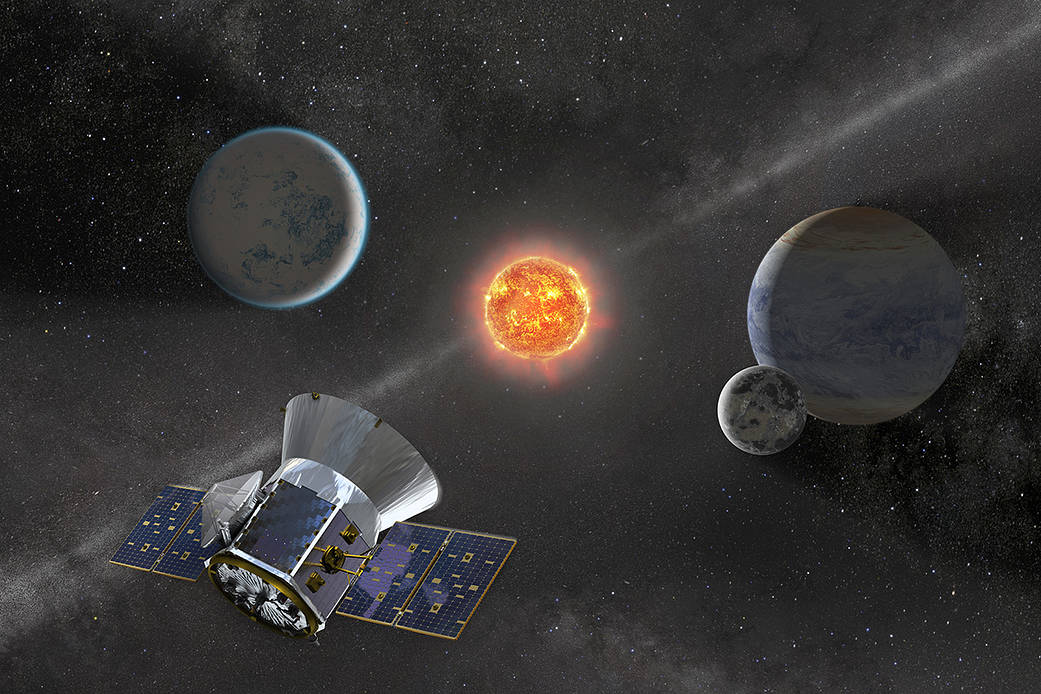

But there is some good news on the horizon for astronomers, astrophysicists, planetary geologists, and people who just like learning neat things about far-away worlds. It’s TESS—short for the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. If all goes well*, the new telescope will launch this week aboard a Falcon 9 rocket. It’s a relatively small satellite, but researchers have giant hopes for what it might discover. It has the potential to identify thousands of new planets, hundreds of rocky worlds like Earth, and dozens of planets hanging out in their star’s habitable zone (where liquid water could exist on the surface), all within our own little corner of the galaxy.

How it works

“Kepler was amazing, and Kepler’s legacy is that we now know that there is a huge diversity of planets out there,” says Lisa Kaltenegger, Director of the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell and a member of the TESS science team. Kaltenegger and her colleagues want to build on the knowledge gained from Kepler and take a closer look at some exoplanets that are hanging out around stars a little closer to home.

TESS will systematically examine 85 percent of the sky seen from Earth, focusing on the stars visible in the northern hemisphere for one year, and the southern hemisphere for the next year. It will keep its peeping within 300 light years away from Earth. That might seem like a large distance, but to an astronomer, it’s right in our neighborhood. To put it in perspective, our galaxy is about 100,000 light years across.

”If you think about it, the closest star, Proxima Centauri, is about 4 light years away. We are looking at everything that is bright and close out to 300 light years, so about 100 times that distance, and there’s a huge number of stars that we can look at,” Kaltenegger says.

Within that range, TESS will watch over 200,000 stars for evidence of planets over the course of a two-year mission, taking pictures of a segment of the sky every 30 minutes for 27 days. As with Kepler, researchers will use TESS to watch for moments when stars dim, which happens when a planet passes between the star and TESS. The dips in light can tell us a lot about a planet’s size, shape, and what it’s made of.

“We don’t have any ships or vehicles yet to get there, but light travels the universe for free,” Kaltenegger says. “So we can do this exploration even though we don’t yet have any physical way to actually get there.”

TESS will particularly look for planets around bright stars, much brighter than those Kepler studied. The brightness of the targets means that other, more powerful telescopes—like the forthcoming James Webb Space Telescope and ground-based instruments—will be able to look for even finer details of those planets, including their potential for life.

Looking for life

With TESS, researchers will find thousands of planets, take the measure of their masses, and observe strange stars. Some researchers, like Kaltenegger, hope that they will point toward a planet other than our own that might have life.

“My passion is trying to figure out if we are alone in the universe, and what we need for that is planets where we can explore the air, where we get enough light to look at the atmosphere of those planets. [That means] we need planets that are close by, and that’s what TESS affords us,” Kaltenegger says.

Kaltenegger and her colleagues can search for signs of life by watching for worlds with large amounts of unstable compounds in their atmospheres, including oxygen. Oxygen makes up a disproportionate amount of our atmosphere because it is a byproduct of many living organisms. A similar atmospheric imbalance on another world, and especially the presence of multiple gasses that don’t belong together, could indicate the presence of life.

Scientists can tell the composition of another planet’s atmosphere by looking for parts of light that vanish as the globe passes in front of its host star, and reappear when the planet has moved on. Those missing pieces correspond to particular molecules (water, oxygen, and methane, for example) in the planet’s atmosphere that absorb specific parts of the light.

TESS wouldn’t be taking those measurements, but it would point to promising candidates for more stringent examination by JWST or ground-based telescopes.

“It will be the first time in human history that we have the technological means to answer the question ‘are we alone?’” Kaltenegger says.

When does it launch again?

Barring technical glitches, bad weather, or other strange and unfortunate events, TESS will launch on Monday, April 16, at 6:32 p.m. eastern.*

- UPDATE: Looks like the technical glitch wins. SpaceX scrubbed the Monday launch so that their team could conduct additional analysis on the guidance, navigation and control systems. They are aiming for another launch attempt on Wednesday, April 18.