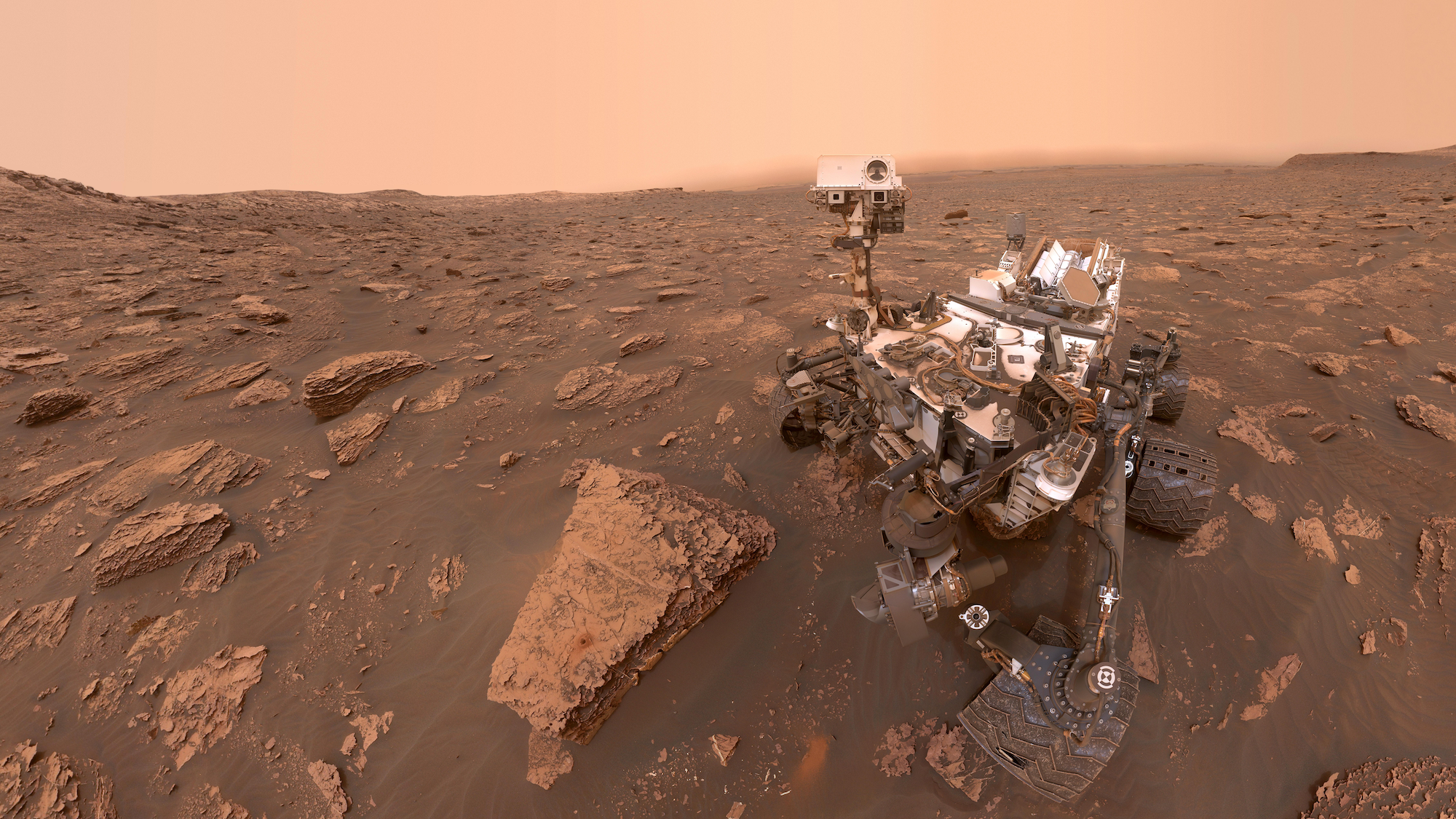

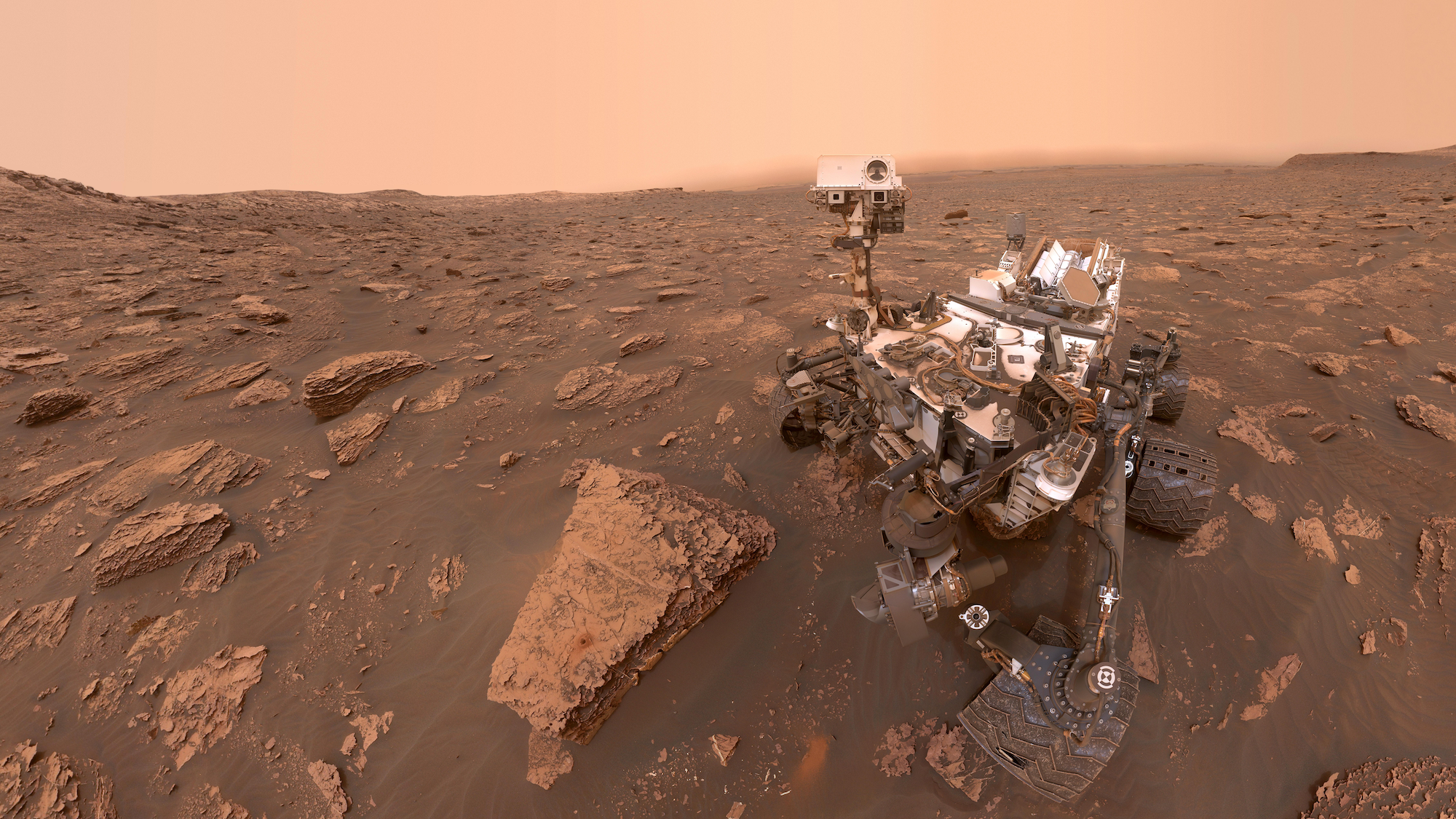

It’s been a big month for Martian winds. Last week, audio recordings revealed the sounds of an actual dust devil traveling across the Red Planet’s surface. On Monday, a team of researchers released a study in Nature Astronomy detailing how some of these very same breezes could help provide energy to future human settlements at a rate far higher than previously believed.

As also reported in earlier rundowns courtesy of New Scientist and Motherboard, past assessments once deemed the winds of Mars too weak to provide a reliable, major source of power production, especially when measured against alternatives like solar and nuclear energy. This stems from the planet’s relatively thin atmosphere—just 1 percent of the density of Earth’s—which generally results in low force winds capable of moving flecks of dust and rock, but not much else.

[Related: For the first time, humans can hear a dust devil roar across Mars.]

However, a team led by Victoria Hartwick, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA Ames Research Center, used a state-of-the-art Mars climate model adapted from a similar, Earth-focused program to factor in the planet’s landscape, dust levels, solar radiation, and heat energy. After simulating years’ worth of weather and storm patterns, the group found substantial evidence that multiple regions of Mars could provide reliable wind alongside other sources like solar panel arrays. Not only that, but certain areas could generate enough power from wind alone to keep a base up and running.

Particularly suitable locations include crater rims and volcanic highlands, while winds blowing off ice deposits during the northern hemisphere’s winter produce essentially a “sea breeze” effect on the surrounding areas that could also be harvested for energy. In certain locations, average wind power production even came in as much as 3.4 times higher than solar, according to the study. In their findings, Hartwick’s team propose the construction of 160-foot tall turbines in seasonally icy northern regions of places such as Deuteronilus Mensae and Protonilus Mensae, along with similar structures around crater edges and volcano slopes.

[Related: NASA could build a future lunar base from 3D-printed moon-dust bricks.]

Unfortunately, because of traditional turbines’ weight, the additional rocket storage bulk could pose logistical and financial barriers. As such, the group’s paper encourages additional explorations into new construction designs, such as low-volume, lightweight balloon turbines and building from materials harvested on Mars itself—a concept that is already being explored for NASA’s upcoming return to the Moon in anticipation of an eventual permanent lunar base.