Human bodies can reject organ transplants at any time—sometimes even years after the procedure itself. When this occurs, time is of the essence to potentially save not only the organ’s viability, but the life of a patient. Unfortunately, noticeable symptoms of organ rejection can show up late, but a tiny new medical device is showing immense promise in offering dramatically earlier detection times.

As detailed in a new study published September 8 in the journal Science researchers at Northwestern University have developed an ultra-thin, soft implant that adheres directly to a transplanted organ’s surface to monitor its health. In small animal clinical trials involving kidney transplants, rejection warning signs were identified as much as three weeks earlier than current methods.

[Related: The first successful pig heart transplant into a human was a century in the making.]

“I have noticed many of my patients feel constant anxiety—not knowing if their body is rejecting their transplanted organ or not. They may have waited years for a transplant… [t]hen, they spend the rest of their lives worrying about the health of that organ,” Lorenzo Gallon, a transplant nephrologist at Northwestern Medical who led the study’s clinical portion, said in a statement. “Our new device could offer some protection, and continuous monitoring could provide reassurance and peace of mind.”

According to John A. Rogers, a bioelectronics expert who led device development for the project, identifying rejection earlier can allow physicians to administer various therapies to prevent a patient from losing the organ, or even their lives.

“In worst-case scenarios, if rejection is ignored, it could be life threatening,” Rogers said via Friday’s statement. “The earlier you can catch rejection and engage therapies, the better. We developed this device with that in mind.”

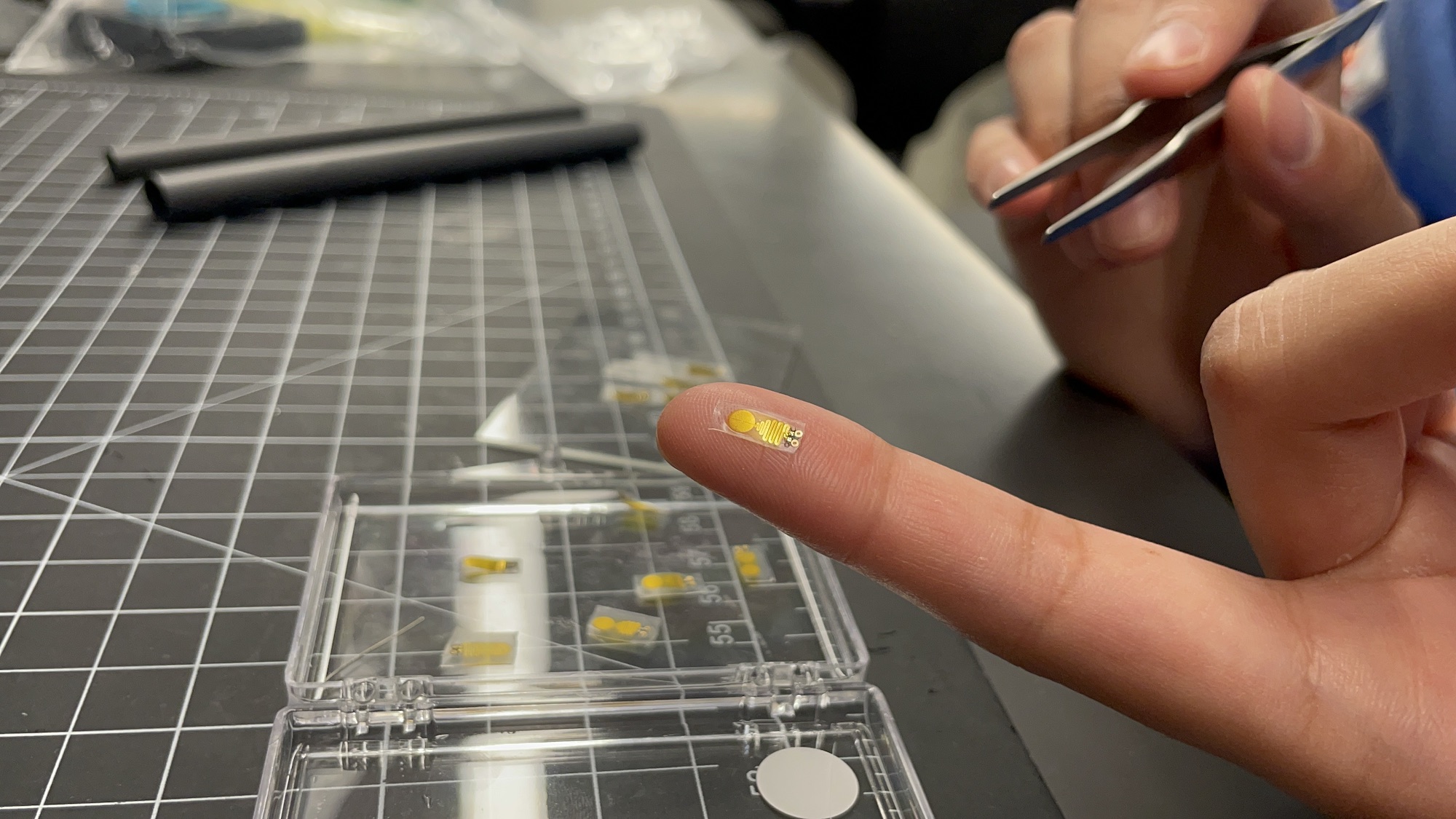

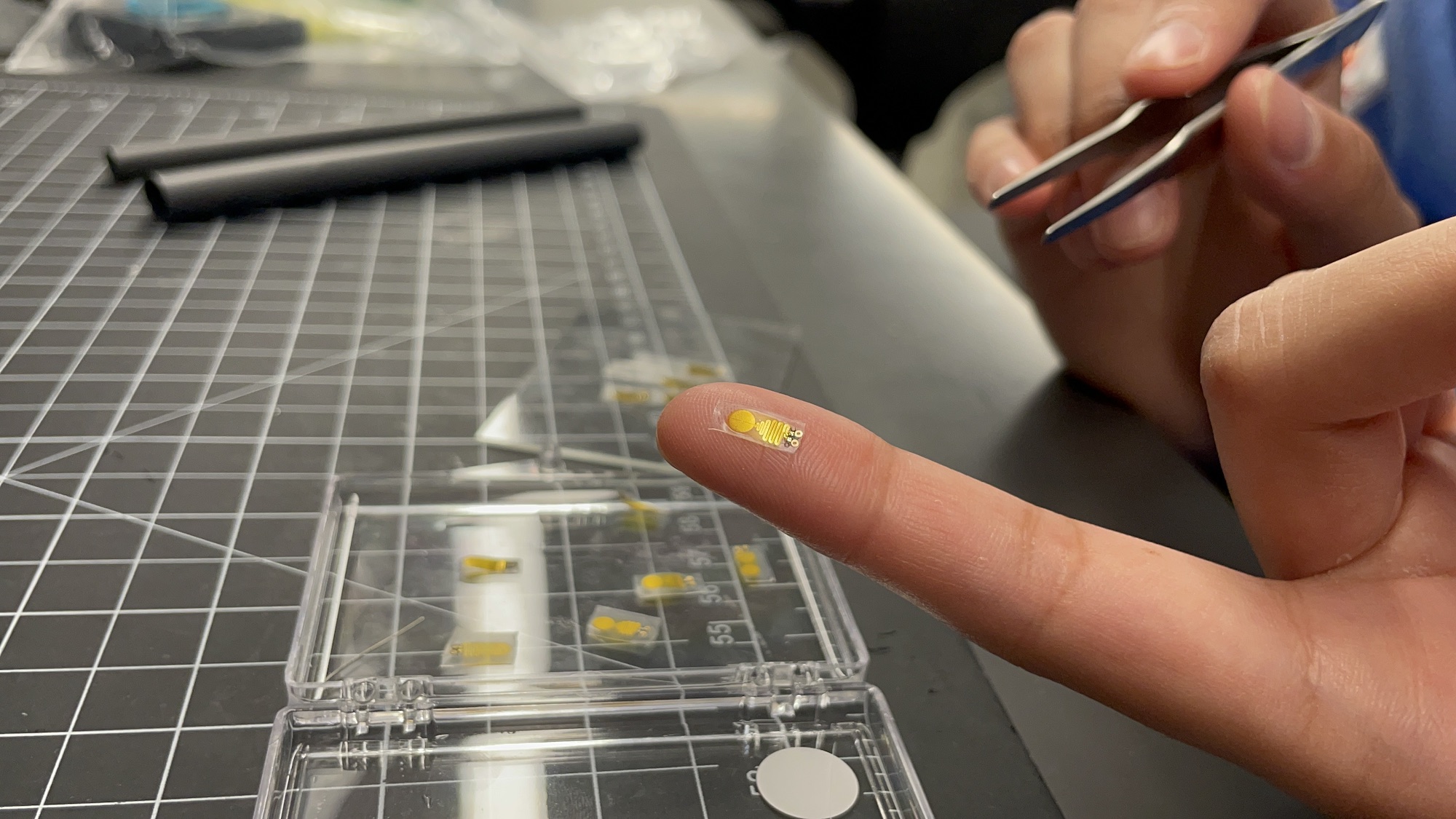

At 0.3 cm wide, 0.7 cm long, and just 220 microns thick, the new sensor is thinner than a single human hair and smaller than your pinky fingernail. The device’s tininess is key to its ability to adhere, slipping beneath a kidney’s fibrous renal capsule layer to rest directly against the organ. Once positioned, the device’s extremely sensitive thermometer measures kidney temperature fluctuations as miniscule as 0.004 degrees Celsius. A miniature coin cell battery currently powers the device alongside Bluetooth capabilities to wireless stream data results to researchers.

Since tissue inflammation is often an early sign of complications, researchers were alerted much faster to potential problems than currently available detection methods like creatine and blood urea monitoring. Due to normal body fluctuations, those existing options are also far less reliable and sensitive than the new device.

“Bodies move, so there is a lot of motion to deal with. Even the kidney itself moves,” Rogers continued, explaining that the organ’s soft tissue isn’t ideal for suturing. “These were daunting engineering challenges, but this device is a gentle, seamless interface that avoids risking damage to the organ.”

Moving forward, the team intends to begin larger animal trials, along with potentially expanding to test on organs such as livers and lungs. They also hope to integrate new power sources capable of externally recharging the device’s battery, thus offering a more permanent monitoring solution.