While touting space as the next great frontier, we tend to forget that our oceans encompass domains that might as well exist on other planets. Like outer space, the deep sea isn’t an easy place to access, but explorers reared on Jules Verne and tales of the giant squid couldn’t resist the challenge of mapping Earth’s most alien habitat. To that end, innovators like aqua-lung inventor Jacques Cousteau, Swiss physicist Auguste Piccard, and aviation pioneer Edwin Link built submersibles fit for the long and treacherous task. As Piccard once said, “Exploration is the sport of the scientist.”

Click to launch the photo gallery.

By definition, submersibles lack the autonomy, power, and size of submarines. Most of the vehicles covered in this gallery couldn’t function unless they were tethered to a surface ship. While Edwin Link dreamed of using submersible to facilitate week-long “camp outs” under the sea, these vehicles were barely equipped for comfortable living. But for the purposes of exploration, leisure, and even undersea farming, they were perfect (well, as perfect as technology back then would allow).

Appearance-wise, early submersibles shared more in common with land vehicles than military submarines. Early diving cars were squarish, had four wheels, and lacked windows. One even came with a large crane for harvesting sea sponges. This all changed in 1928 when Otis Barton convinced naturalist William Beebe that a small spherical vessel was best suited for resisting the ocean’s crushing pressure. Six years later, Beebe and Barton set a diving record when their Bathysphere descended 3,028 feet, making Beebe the first marine biologist to study deep-sea wildlife in its natural surroundings.

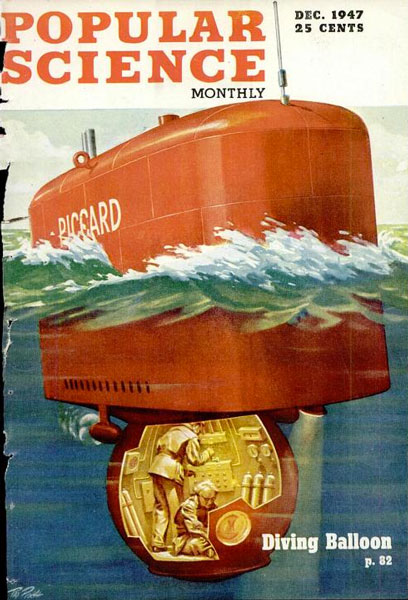

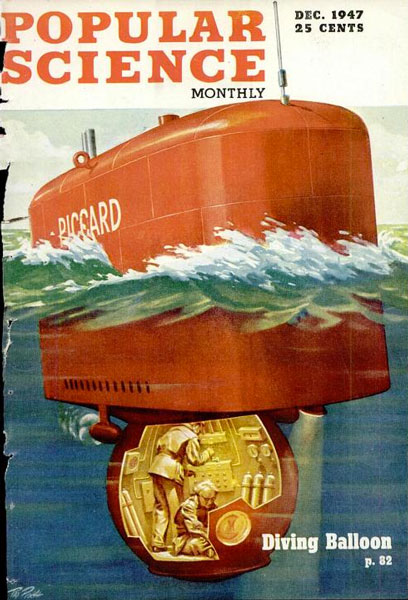

Naturally, the Bathysphere’s renown drove Beebe’s peers to emulate his success. Auguste Piccard, who had previously set an altitude record while ballooning, developed an interest in adapting balloon technology for undersea vehicles. The result? A spherical cabin suspended from an enormous buoyancy device containing 10,000 gallons of aviation gasoline. Piccard’s work reaped an incredible reward just two decades later, when his son Jacques Piccard and Lt. Don Walsh became the first (and so far, only) men to reach Challenger Deep, the deepest known point in the world’s oceans.

Click through our gallery to read about the Bathysphere, the “U-Drive U-Boat,” and other submersibles from decades past.