An oil-free deep fryer, which its inventor hopes could hit the market later this year, could let health-conscious consumers have their donuts and eat them, too.

Call it an infrared-wave, radiant fryer, or miracle oven — it makes french fries with half the fat, no engineered chemicals like Olestra, and the same crispy, oily goodness we all know and love.

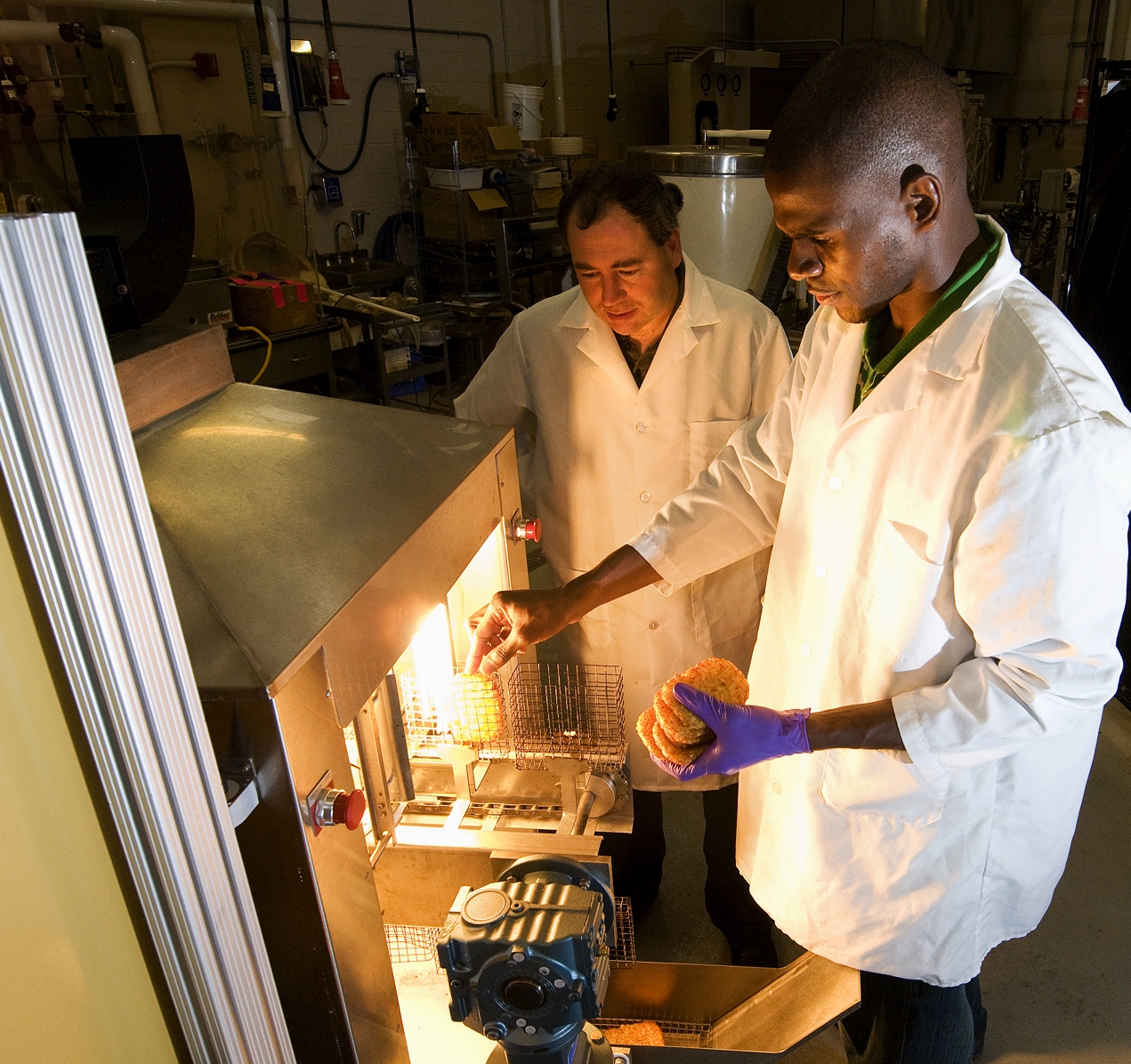

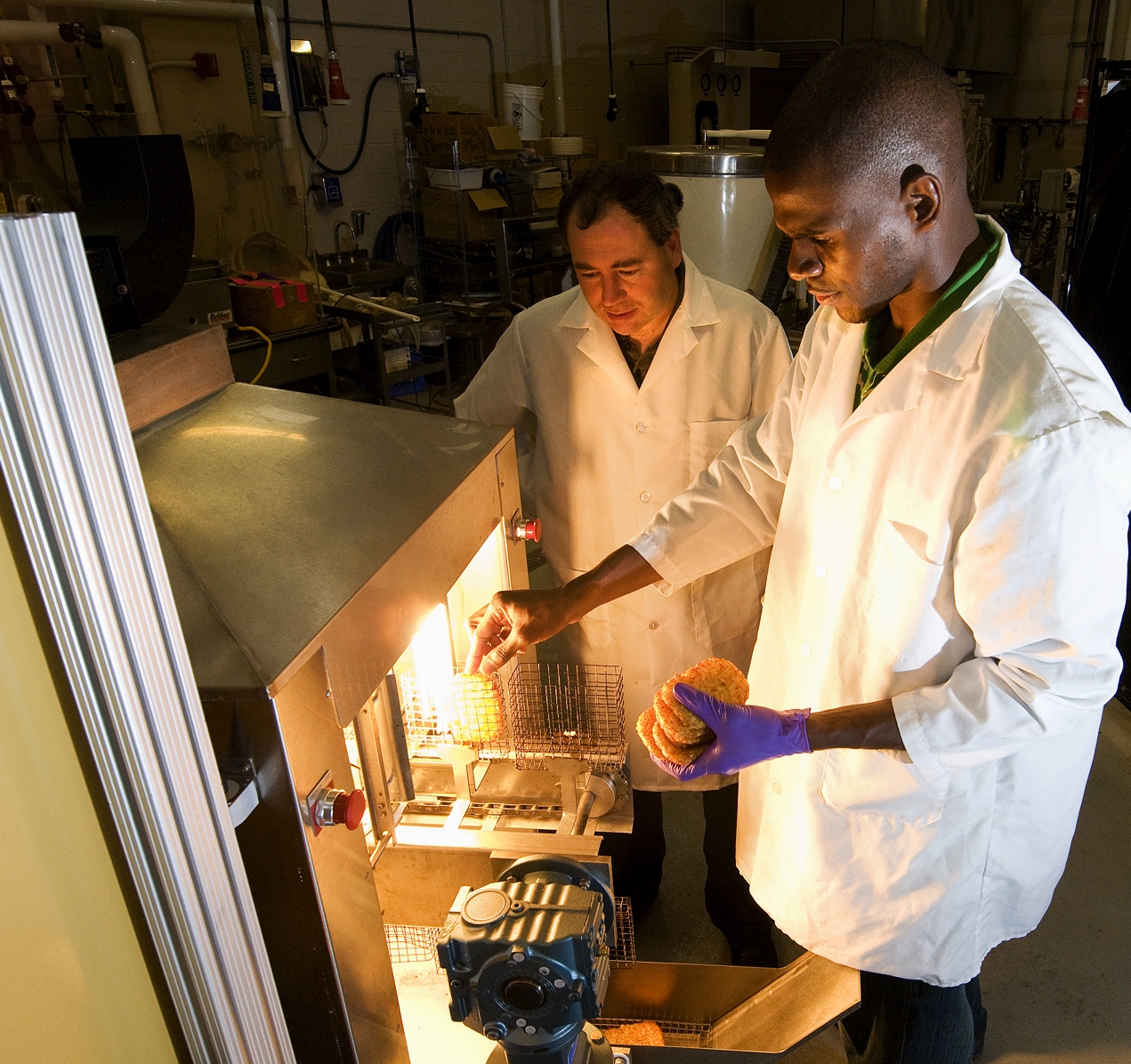

The radiant fryer, developed at Purdue University by food scientist Kevin Keener, is meant for foods with just a little bit of oil on them already, like the par-cooked chicken nuggets, hash browns and french fries you’d find at a fast-food restaurant. And that’s the target, Keener said.

“You can dial in (a heat level) for a certain product. That would allow a restaurateur to provide on-demand products,” he said. “You’d pay your money, and within two minutes, your order is coming out of the fryer hot onto the bun and they are putting it on your plate.”

Though Keener said he’s gotten a few calls from consumers who want one at home, he says the oven would need further refining before it could be built for personal use.

Keener started working on the oil-free fryer seven years ago, while he was at North Carolina State University. He and colleague Brian Farkas thought it would be smart — and profitable — to come up with something that fried food faster, healthier and safer than hot oil.

Farkas had already published a paper on the heat flux of french fries cooking in hot oil — basically, the energy flow required to get the fries hot enough so they would be cooked properly and taste right. He came up with a heat flux of about 30,000 watts per square meter.

Few other methods of heating can achieve those heights. Blowing hot air, for instance, only gets you about 10,000 watts per square meter. Conduction (like using a frying pan) can get very hot, but it’s not as fast, and there are problems creating a uniform crust. Keener and Farkas thought of using radiant energy, like the kind that comes from the sun. They settled on infrared, which doesn’t penetrate food as far as microwaves, but shares some similarities.

Keener moved to Purdue University in 2005, and started work on the prototype oven, which Indiana-based Anderson Tool and Engineering Co. built last fall. The contraption can generate 100,000 watts per square meter and make a tasty chicken nugget. “It would turn anything to a crisp,” Keener said.

It’s essentially a glorified heat lamp, using 10-12 infrared emitters with different wavelengths. Each has a different purpose — some cook the middle, some heat the surface, and so on. Jalapeno poppers work well because the inside can be cooked at a much lower temperature than the exterior, for instance. “We just literally change the dial on our emitter setting,” Keener said.

In a demonstration, Keener cooked hash browns and chicken patties that he claims tasted even better than traditionally cooked ones. “You can taste more of the food and less of the oil,” he said.

It’s also healthier than traditionally fried food, because less oil is used. Various goodies contain 30 to 50 percent less fat than their traditionally cooked counterparts, Keener said. “All you really need to enjoy the fried characteristics is a small amount of oil on the surface,” he said. “All of these foods that are fried at (places like) McDonalds, that’s the second time they have been fried, so they are picking up additional oil. Most of the fat reduction rate we are able to achieve is the result of not frying a second time.”

Several companies have expressed interest, and negotiations are ongoing; Keener said he hopes to have a manufacturing agreement sometime this spring.

One drawback: It won’t fit a turkey.

“There are limitations,” Keener acknowledges. “You can literally throw anything in hot oil — a turkey, a Snickers bar, you name it and it will fry it. WIth this system, it really needs to be a formed product, something that is portion-sized so we have control over the geometry and the composition.”

Lightning in a Bag

In addition to making fried food less fatty, Keener is tackling the safety of our packaged foods.

He’s working with a byproduct of plasma studies done on behalf of the military. The armed forces have been interested in plasmas for everything from propulsion to treatment systems, including biological decontamination. Some plasmas are known to be bactericidal, Keener said. While at North Carolina State, Keener and colleagues built a chamber to test food decontamination, with an eye toward eventually testing larger, military-sized things. But when he went to Purdue, there wasn’t enough money to build another chamber, so he had to improvise.

He and a research assistant, Paul Klockow, built an electrode system that can be used to generate plasma fields inside a sealed container. Two electrodes create enough voltage to ionize the gas inside the container, creating a plasma field.

The first contraption involved a 15,000-volt neon light transformer, some wires, and a plastic bag full of helium. Keener used it to ionize a bag of tomatoes — it looks like a baggie full of purplish lightning.

“It’s something you could build in your garage, if you were mechanically inclined,” Keener said.

The system can be used to eliminate bugs like E. coli or salmonella in food products or for medical applications, Keener said. Treatment could take from several seconds to a few minutes, depending on the items.

“We can ionize any gas that is inside of those (packages),” he said. “When we ionize it, it turns into bacteria-killing molecules.”

Food packages usually include gases designed to increase shelf life or kill bacteria. But the electrode system can use plain air, Keener said. Ionized air creates ozone, which kills bacteria but doesn’t harm the food. The Food and Drug Administration approves the use of ozone to ionize the water that’s used to wash vegetables and fruits, Keener said. But the benefit of his device is that it all happens in one sealed bag, lowering the chances of contamination.

So far, the device can ionize a gallon-sized container using only about 30-40 watts. Keener just bought a 130 kilovolt system, which he hasn’t started testing yet.

Only one problem so far — it turns spinach white. But Keener said it still tasted just fine.