You’d be hard-pressed to find a consumer tech company that isn’t selling a wearable device, or at least thinking about it. Whether for health or fitness, plenty of people are strapping on sensors to gather data. At South by Southwest this year, Dr. Leslie Saxon, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Body Computing at the University of Southern California spoke about the future of where that biometric data will take us for an IEEE panel. Her vision for it goes beyond a watch or wristband.

Popular Science: How did you start this work?

Leslie Saxon: I started the Center for Body Computing at the University of Southern California eight years ago. I’m an interventional cardiologist and I implant defibrillators, which are devices that are about $30,000, and prevent sudden cardiac death by delivering a shock. The prior paradigm was, you put one of these devices in, you nominally programmed it, the patient came back every four months, and you spent five minutes doing custodial stuff. It was like buying an expensive car and never programming the car radio or using any of the features.

I realized that by checking every day on patients’ status wirelessly, we could make observations not just over my 700 patients with these defibrillators, but over the entire country. So I started this research organization where we were at one point following 400,000 people that were wirelessly transmitting every day. And we made all these important observations and showed that if you did that patients lived longer. And that is when mobile, and digital, and Internet connections and cloud storage and worldwide networks were happening at the same time.

Instead of having these scenarios where you saw the patient .001% of their life, only if they had a symptom, we could use implantable wearable sensors so that we could take care of people continuously and on demand. Not only that but we could have people push information and we could amass these big data clouds, just like companies such as Waze have done with traffic.

What will all this data mean to people?

We’d be able to say okay, you’re going to get this illness, so, go to a doctor. Or, if you know your kid has strep throat, you can know ‘do I stay home from work, what other kids that I have are going to get sick?’ You could suddenly start making these observations. And at the center, I got the idea it should incorporate a social network.

Everybody that’s trying to manage a medical condition has some social community around them, even though they may not be using Facebook. So, why not provide this social community that’s capable of asynchronous communication around the care paradigm. So what we’re working on is, if we build an application or a solution, you let the patient involve their care providers, the daughter, the husband, wherever they are, you involve the doctors, wherever they are, and you have them all communicate asynchronously, and it provides the doctors more autonomy and more accurate continuous information. This way, the patient can share data immediately with everybody so there’s no loss in translation.

What are you hoping to gain from this data sharing?

If we’re going to provide continuous medical therapy all the time, I thought, why don’t we start young? We know when people are healthy–my 11 year old son is healthy. We know when people are sick–my 82-year-old dad is sick. And we know nothing about all of this time in between. So, why don’t we just define this transition from health to disease by monitoring the world all the time.

How is all this monitoring going to happen?

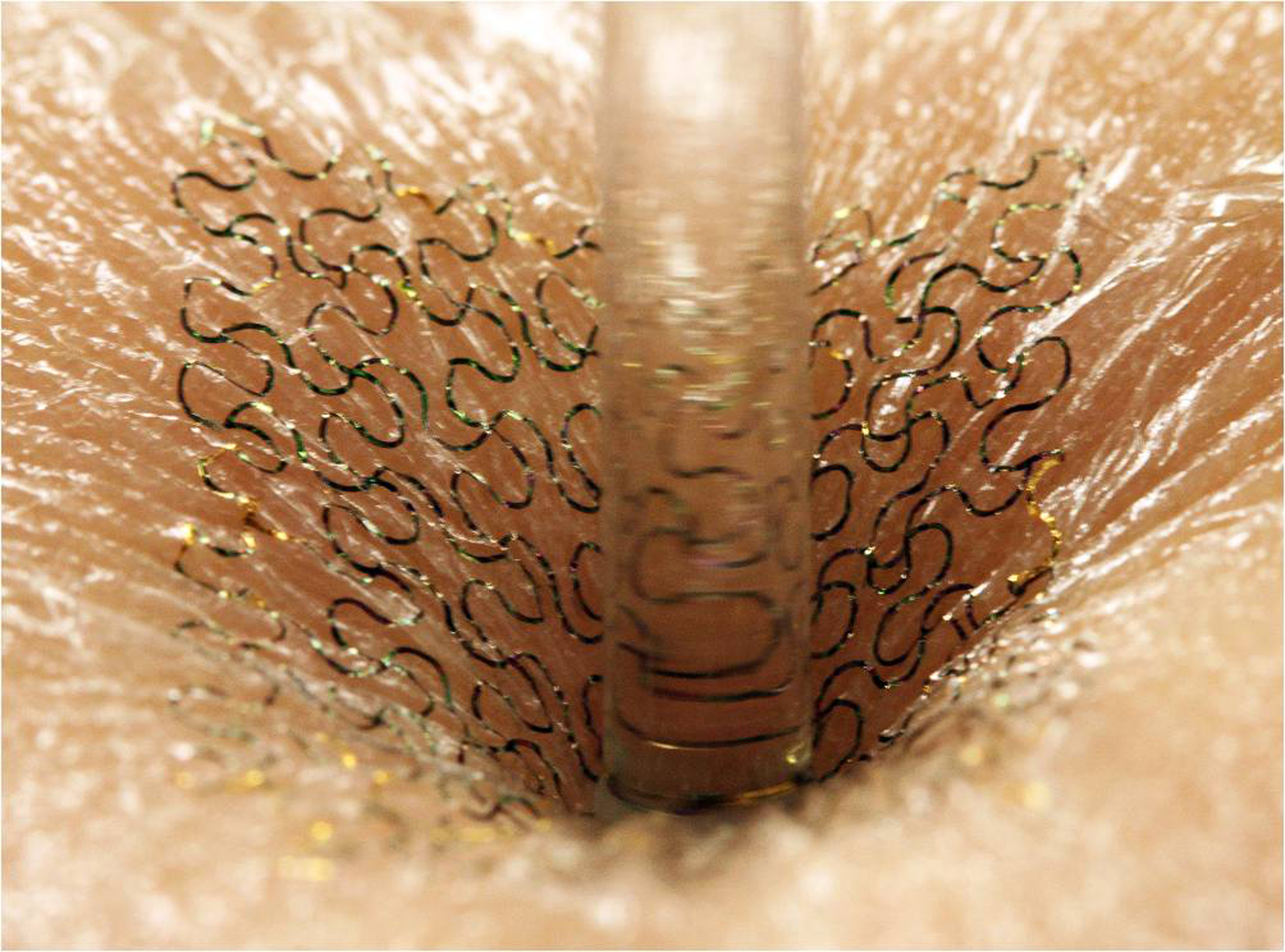

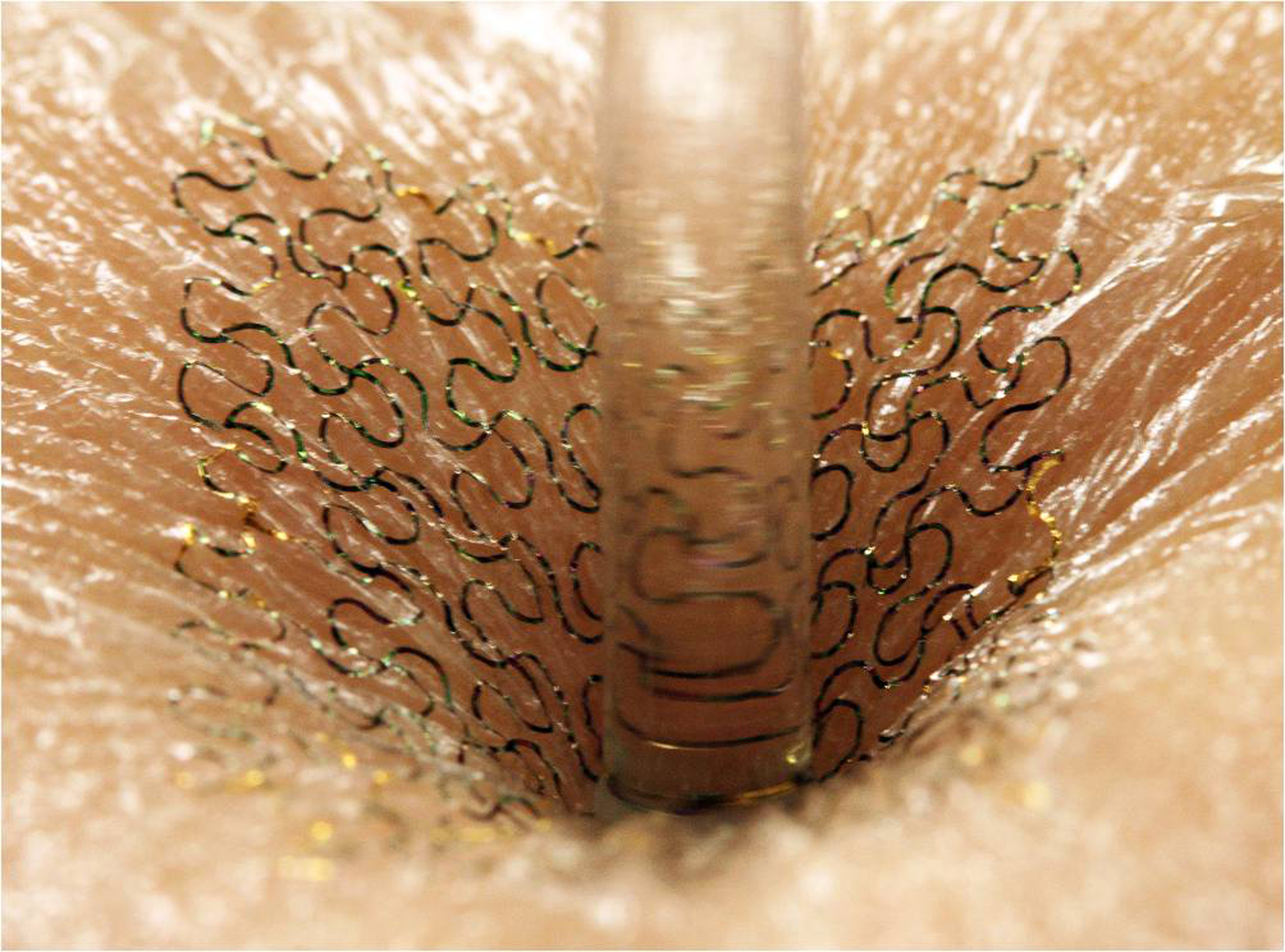

We just built a photo-sharing app called Biogram, which you can download from the app store. It allows you to put this sort of bio tattoo on your photo. So, you can measure your heart rate through any means you want and broadcast it. My kids are photo-sharing all the time. You stamp your heart rate and then you send it, and it’s like a window to your soul. People know how you’re feeling about that moment, and you can find out your friend’s heart rate. But, in doing that, you’re building this huge biometric cloud, so by the time you’re 16, you have more medical data in the cloud than any high-end patient that maybe gets a heart transplant, and it’s all passive.

Imagine: you go to the Apple retail store and get injected.

PS: What about the wearable sensors we have out now?

120 million Americans are using dumb sensors right now. They’re just directional accelerometers. You could carry your phone around and get the same thing. But the sensors are now becoming better,and the integration is becoming better. So, now I’m very interested in building–because I like implanted stuff–an invisible, implantable sensor, that’s just injected. Imagine: you go to the Apple retail store and get injected. What if I told you I could get chipped, and you’d have three years of wireless, unbelievable sensing.

We’re piloting wearables and thinking about implantables in elite athletes, where we’re trying to prevent injury and enhance performance. But you really need more data and you need it all the time. You don’t just need it during the game. You need to know how much they sleep, are they hydrated going in, how do they feel? Are they sore? How do you train them? So, this kind of body computing has taken me from hardcore medicine, to elite athletics, to some military applications, to a lot of popular culture stuff.

How do you get people interested and invested in health tracking if they may not need it like those with chronic conditions?

Part of it is you leverage things they’re already doing. The smartphone’s good because people are already checking it 150 times a day. But what’s the secret sauce to create engagement? One of the things is, you really have to have accurate sensors, you have to have real data you can count on because you’re going to be making predictions. But the other thing is, the social network concept is really powerful because people check their social networks every day.

In this space between the healthy and the sick, what are you hoping the data amount to?

Usually, there’s not one magic bullet that causes cancer or heart disease or depression or obesity. It’s a mashup. So with digital, you can say, imagine if you had maybe a genetic propensity to a certain kind of cancer, or childhood asthma, and you were moving, you were thinking of buying a house and someone could tell you, based on your biometrics and what factories are around you or what waste cleanups have happened: Your odds of getting breast cancer are much higher if you live in Marin County than if you live in Oakland. Or, if you live in Brooklyn versus Long Island.

I would imagine a world where people can actually make those decisions with much more information, or it turns out that your pregnancy could be complicated by hypertension, and this is based on data we’re collecting from you, and everybody like you in the world.

Do we have the technology now to create the implantable sensors you’re talking about?

Yes, we do. It’s a culture thing. I think, if you’re going to stick something under somebody’s skin, even if it’s minimally invasive, you have to offer a value proposition. Things like tattoos are completely acceptable. So, if you’re game for that, this is an even more dynamic thing. But there’s a fear around it that’s legitimate, which is: if I’m chipped, who can access it?

Do you think there’s a perfect privacy balance?

No, I think it’s a tradeoff. I think society now is willing to give away anything for efficiency. With medicine, something so highly personal, you don’t want that. But there’s such an upside. With devices like the Apple Watch, it seems like their philosophy is “okay, you’ll have this experience, it will live on your phone, and the company won’t collect the data.” So if you’re an obese hypertensive diabetic, and you only want your doctor to see your blood sugar is controlled but your weight went up, you can just share your blood sugar.

I don’t really like that. From the global health perspective, unless you have everything, you’re not going to be able to get that full picture. So you really need it all and it has to be accurate. On the other hand, that method highly protects the privacy of each individual. So, what I’d like to see is almost a UN for digital health, some kind of global governance in the interest of the individual. In the future, think about being able to predict an Ebola outbreak so you can prevent kids from dying. But if you’re going to expose somebody’s very private medical data, is it worth it?