The biggest clamors most of us will experience are things like jackhammers and jet engines, but the most ear-shattering noises in existence would do far worse than make you wince. Events on the scale of volcanic eruptions and exploding meteorites register at more than 194 decibels, a level that generates enough force to potentially pierce your eardrums and pop your lungs. At those highs, sound waves are so powerful, they no longer slip through the air but rather shove molecules out of their way. Decibels can’t even accurately measure these bangs; researchers instead quantify them by the amount of energy they release—like they do for bombs or other explosives. Here are some of the most deafening things on Earth, both natural and mechanical, including the absolute biggest kabooms ever recorded.

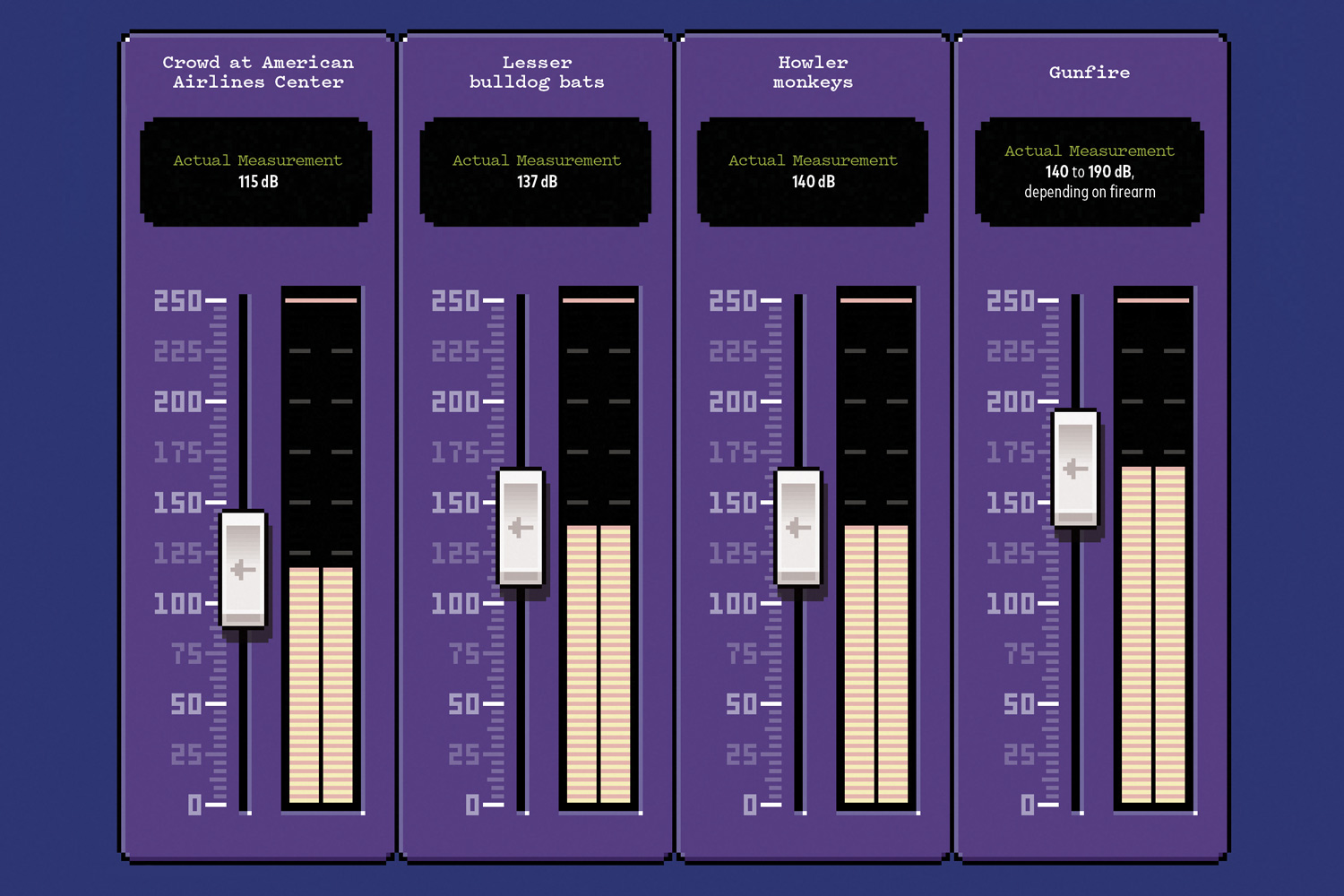

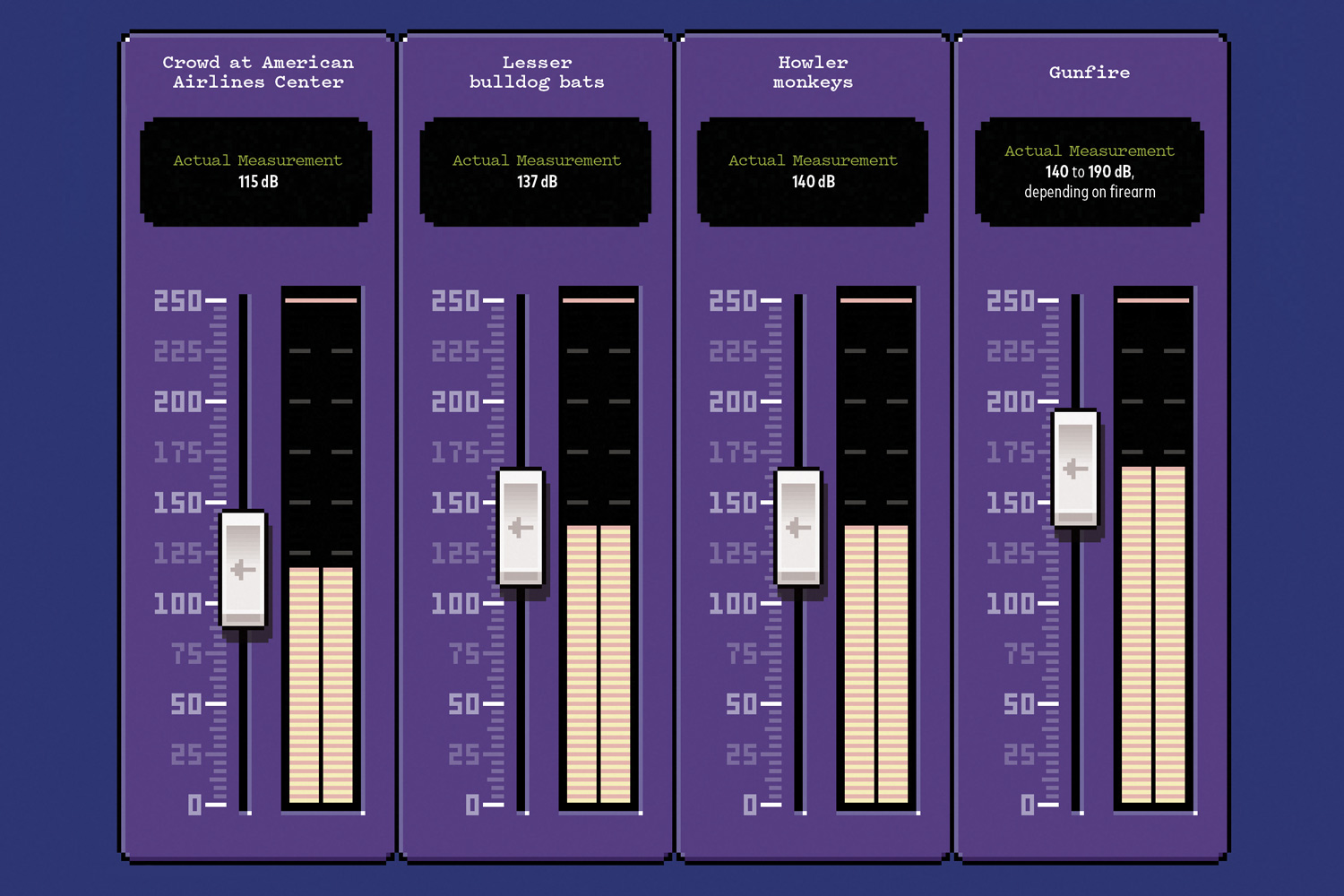

Crowd at American Airlines Center

(Actual Measurement: 115 dB)

Ahead of the 2011 NBA playoffs, Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban had the team’s home stadium outfitted with a revamped acoustics system. Microphones in the backboards transmitted sneaker squeaks and players’ voices through 60 gargantuan speakers, which also amplified and circulated sounds from the crowd. Fans couldn’t get enough of the din. As time expired and Dallas emerged victorious after a seemingly impossible comeback, the audience roared at 115 decibels—exactly the threshold for human pain.

Lesser Bulldog Bats

(Actual Measurement: 137 dB)

Down in Central and South America, this mammal produces an ear-shattering cry that would be downright painful to us— if we could hear it, that is. Their calls are ultrasonic, meaning their pitch is above limits of our perception, so our feeble human ears fail to take notice. High-frequency sound doesn’t travel exceptionally far, hence the need for an extreme shriek to extend hunting range. The bats’ super-powered volume helps them use echolocation to zero in on small, swift insect meals.

Howler Monkeys

(Actual Measurement: 140 dB)

Howler monkeys really earn their name. The extra-large hyoid bones in their vocal tract house massive air sacs that amplify their bombastic voice to superlative heights; they are often regarded as the loudest of any land animal. When groups of them start, well, howling, the ruckus is audible from 3 miles away. Primatologists theorize that the monkeys do this as a way to tell any potential intruders that their territory is very much occupied—or possibly as a way to guard their mates.

Gunfire

(Actual Measurement: 140-190 dB)

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, any noise louder than 120 decibels can immediately damage the tiny hair cells that help turn vibrations into what our brains perceive as sound. Most guns, like pistols and rifles, clock in around at least 140 when fired. Neglecting proper protection often results in permanent high-pitched hearing loss (particularly s, th, and v sounds) and tinnitus, or ringing in the ears. Most don’t realize there’s a problem until it’s too late.

Saturn V Rocket

(Actual Measurement: 204 dB)

Developed for the Apollo program, NASA’s Saturn V rocket is a decorated record-holder. It is the tallest and most powerful spacecraft to successfully fly. The behemoth has launched 13 times, propelling 260,145 pounds of payload into orbit on each go. A portion of the rocket called the SI-C stage generates around 7.5 million pounds of thrust to do so. All that power translates into quite a bit of noise, which NASA dampens by dousing the launch area in curtains of water to absorb pressure waves.

Chelyabinak Meteor

(Actual Measurement: 90 dB from 435 miles away | Calculated Measurement: 180 dB from 3 miles away)

Type “Chelyabinsk meteor” into YouTube, and you can experience this explosion for yourself. A handful of Russian dashboard cameras caught it on tape. A force equal to 500 kilotons of TNT shattered glass and tossed debris throughout the city, injuring more than 1,000 people. Big booms typically emit a lot of far-reaching ruckus called infrasound, which is too low-frequency for human ears to pick up. Chelyabinsk was no exception, with deep tones hitting sensors 9,000 miles away in Antarctica.

Tunguska Meteor

(Actual Measurement: N/A but registered on barometers as far as England | Calculated Measurement: 197 dB from 3 miles away)

One June morning in 1908, a shock wave knocked a Siberian man out of his seat on the front porch. The Tunguska meteorite was to blame. It had burst in midair 40 miles away with a blast equivalent to 650 Hiroshima bombs. Eyewitnesses said the shattering space rock rang like artillery fire from that distance and was as bright as the sun. There’s no evidence of any fatalities, but the meteorite flattened at least 600 square miles of forest, leaving 80 million felled trees to rest in a radial pattern.

Krakatoa

(Actual Measurement: 172 dB from 100 miles away | Calculated Measurement: 189 to 202 dB from 3 miles away)

When Krakatoa erupted in 1893, it obliterated more than half of the island’s landmass, created 100-foot-tall tsunamis, and deafened anyone it didn’t kill for miles around. The death toll was over 36,000. Zanzibar beachgoers discovered washed-up human skeletons melted onto slabs of pumice as long as nine months afterward. Even thousands of miles away, in New Guinea and parts of Australia, the blast was said to sound like gunfire. Its total power amounted to 200 megatons of TNT, or 13,000 Little Boy atomic bombs.

This story originally published in the Noise, Winter 2019 issue of Popular Science.