After much anticipation, we now know exactly how millipedes have sex. With the help of imaging techniques that take advantage of glowing millipede tissues, researchers have illuminated this arthropod’s intricate mating process. This finding marks the conclusion of a nearly 80-year quest to uncover the millipede’s genital structure.

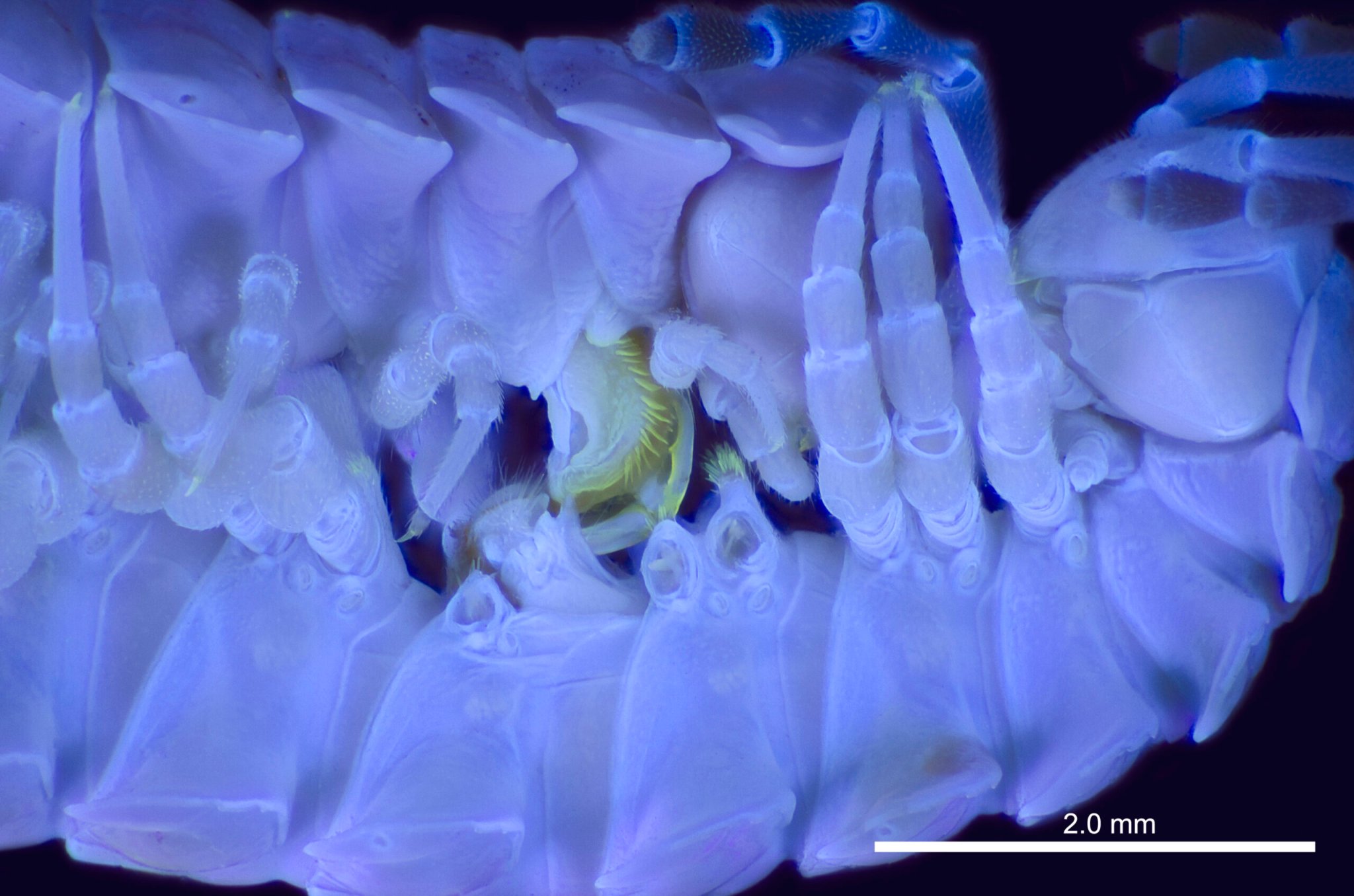

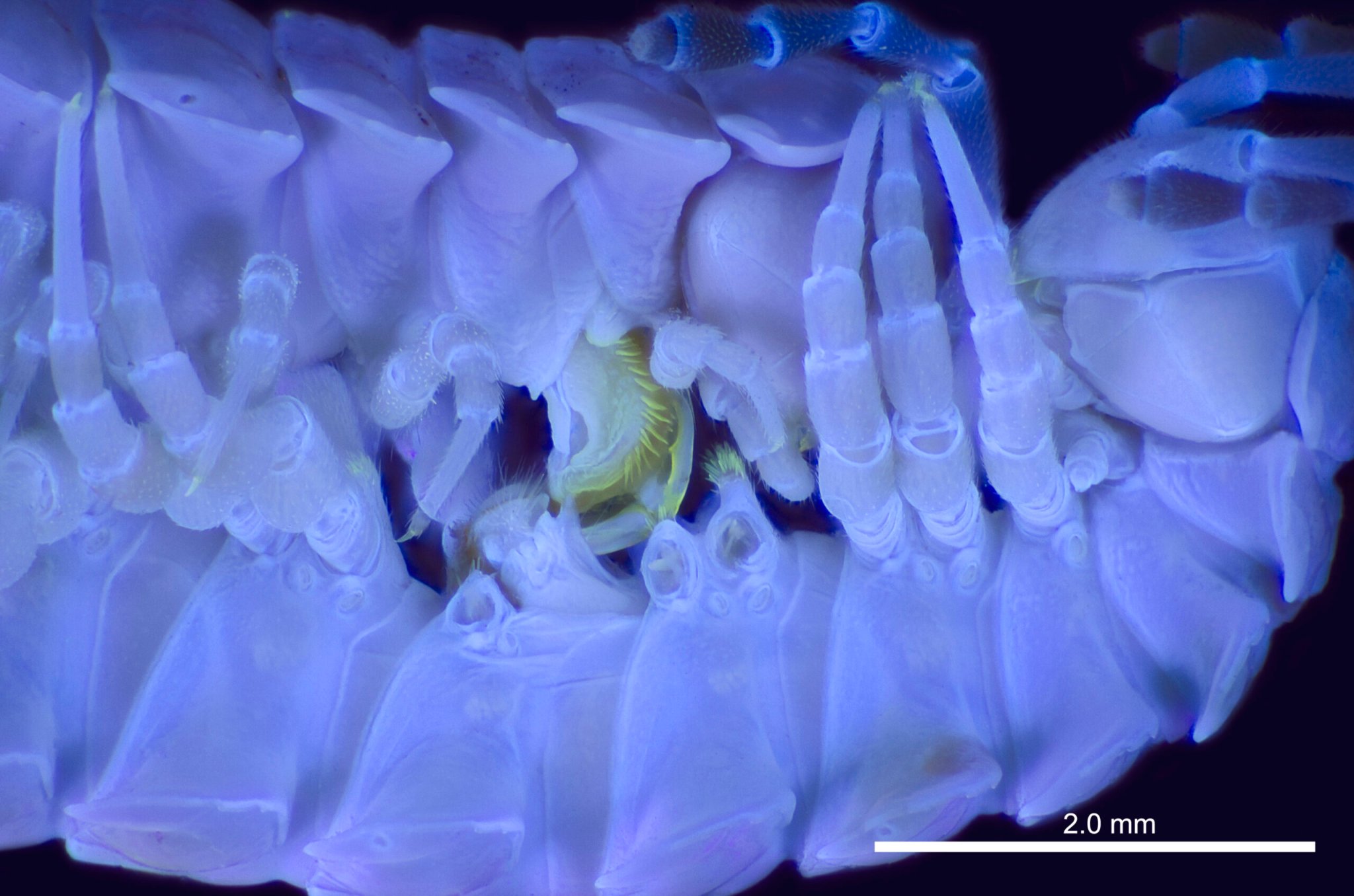

After a pair of millipedes started getting it on, researchers from the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago scanned both individuals and one male-female pair in an electron microscope. They also captured dozens of photos at slightly varying angles on a digital camera. By layering them digitally, they were able to clarify tiny genital details. They photographed the millipedes in both natural and ultraviolet lights, since their genitals glow under UV lighting. In a press release, the Field Museum compared the resulting photos to “a rave, albeit one made up of microscopic millipede genitalia.”

Over at UC Davis, collaborating scientists placed individual millipedes into test tubes and ran micro-CT scans, which captured and layered a series of X-ray images to visualize the bugs in 3D without the need for any dissection. The team published their findings in the journal Arthropod Structure & Development.

By examining the 3D renderings, the researchers noted that male and female millipedes likely mate in a “lock-and-key” formation. Researchers learned that the male’s gonopods—the specialized pair of legs used to insert sperm into the female—first become covered in blue-ish ejaculate. Then, he places a tiny, fleshy part of the gonopods into the female’s vulvae. At this point, the two millipedes “lock” together.

Post-coitus, the female vulvae may seal themselves closed with a gooey secretion that traps the sperm inside. When she lays her eggs, they’re coated with the stored sperm, which completes the fertilization process.

The team specifically studied the Pseudopolydesmus genus, made up of half-inch-long brown millipedes native to North America. There are more than 13,000 known millipede species total, and they each mate in unique ways. But Pseudopolydesmus caught scientists’ attention because they appear especially eager to have sex.

“One of the problems with millipedes is that they do a lot of things while they are dug into the ground, and if you take them out, you will disturb them and they’ll stop what they’re doing,” study author Petra Sierwald said in a press release. “[Pseudopolydesmus] will even mate in the lab in the Petri dish under the light.”

The millipede’s multitude of legs typically obscure the complexity of their mating process. The CT-scanning provided a clear view of the female’s vulvae glands and provided a better understanding of millipede sex mechanics.

Their discovery could eventually aid scientists in understanding the relationship between different millipede species, along with their broader evolution. Right now, for example, we don’t have the slightest idea of what most millipedes’ vulvae look like. Further research could assist in determining their current state of biodiversity, according to a complementary 2019 study.

And as Sierwald noted in the press release, the leggy, promiscuous arthropods could also “tell us about the geologic history of North America. As mountain ranges and rivers formed, groups of millipedes would get cut off from each other and develop into new species.”

Today, the leggy arthropods face challenges from climate change. As the world warms, millipedes will expand north, Sierwald says, just as they did post-Pleistocene as glaciers receded and forests spread. But a more imminent threat comes from deforestation and soil erosion, which devastates leaf litter that millipedes munch on. Conversely, disappearing millipedes could cause an excess of rotten leaves in deciduous forests. On the whole, there’s still a lot to learn about our many-legged friends—and understanding the graphic intricacies of their copulation process is a key step forward.