For February, we’re focusing on the body parts that shape us, oxygenate us, and power us as we take long walks on the beach. Bony bonafide bones. These skeletal building blocks inspire curiosity and spark fear in different folks—we hope our stories, covering everything from surgeries and supplements to good old-fashioned boning, will only do the first. Once you’ve thoroughly blasted your mind with bone facts, check out our previous themed months: muscle and fat.

Don’t judge a bone by its calcified cover. Seriously. Though your skeleton might look bare and bleached on the outside, in reality, it’s packed with diverse cells, tissues, and molecules you can only glimpse through magnified images. Researchers use microscopes and scanners to diagnose different bone conditions and develop treatments, but for the rest of humanity, they reveal painterly vistas of the stuff that makes up your core (literally). Here are six examples of the complex, underlying elements of vertebrate bones, curated from the National Institute of Health’s online gallery.

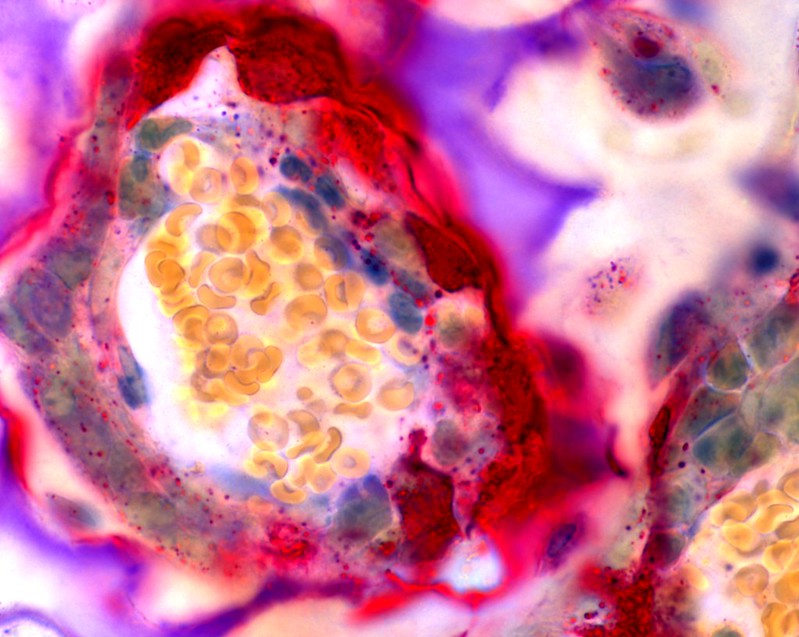

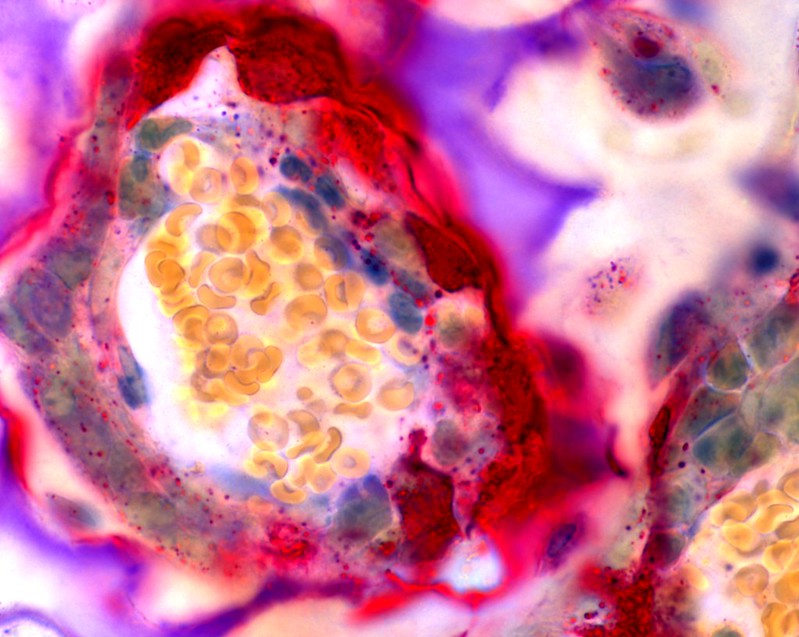

Osteoclasts (above)

One of the common elements found around bones are osteoclasts, super absorbers that attach to hardened surfaces when the body’s calcium levels get too low. From there, they suck up old cartilage and recycle it for the formation of new bones (a role carried out by their counterpart, osteoblasts). Sometimes these cells go into overdrive, however, stripping perfectly good parts of calcium, resulting in osteoporosis. The treatable disease plagues nearly 53 million people in the US each year.

Collagen

The next time you drop top dollar on a collagen supplement or cream, just remember that your body is a goldmine for it. The protein is the underlying ingredient for bones, joints, teeth, and skin; its rope-like texture differs based on what it’s being used for. For instance, it adopts a relaxed form in the skin and a tighter structure in the skeleton to provide the tensile strength behind quick physical motions. Up to 90 percent of a bone’s matrix can be made up of collagen.

Calcium

Collagen is great and all, but you know what bones get even more jazzed about? Minerals. About 65 percent of our bones are made of calcium and phosphorus, which also naturally circulate through our blood. With the help of Vitamin D (and maybe magnesium, the science is still grainy there), these elements work in tangent to form new bones and shore up existing ones—unless there’s an imbalance. Then they get drawn away to other parts of the body, leading to weaker structures that might fracture or wear down more easily.

Marrow

Ah, wonderful life-giving marrow. The fatty tissue in the middle and ends of your largest bones gives rise to the body’s best pinch hitters: stem cells. Different types of marrow—OK, there are only two—have different purposes. The red kind creates red and white blood cells, along with platelets, while the yellow kind serves as a back-up energy source for the metabolic system. It’s the first, however, that’s crucial for transplants in patients with blood diseases.

Cartilage

If your bones are the VIPs of your body, then cartilage is the security detail. The tissue (more stretchy and supple than marrow) caps the ends of joints, like the one between the patella and tibia, absorbing force and preventing friction. But that’s just one of its purposes. In infants, hyaline cartilage, which is less elastic, serves as the stand-in for bone. Their skeletons only start to harden as they collect and produce more calcium through their diets—a process that can take 17 to 25 years in total. More mozzarella, Ma!