Hurricanes are often described as “barreling” through a region, yet some of the most dangerous storms in recent years have exhibited just the opposite behavior: meandering, roaming, and hovering for days on end. This hovering is more commonly known as “stalling,” and occurs when a hurricane more or less grinds to a halt. Hurricanes are stalling more around the world, and some researchers are trying to understand how and if climate change impacts this behavior.

A slow hurricane can be uniquely menacing. If a storm is stationary, it means that the imperiling rains and winds will last longer, prolonging the threat. “I think about it as ‘do you want to do one round in the ring with Mike Tyson or 10?” says Timothy Hall, an expert in tropical cyclones and senior research scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. “Everything about a hurricane is dangerous, and everything about it is worse if you’re standing under it longer.” The most obvious risk of stalling is rainfall accumulating over a longer period of time, but Hall says there is also the threat of winds continuing to drive storm surge and damage human infrastructure.

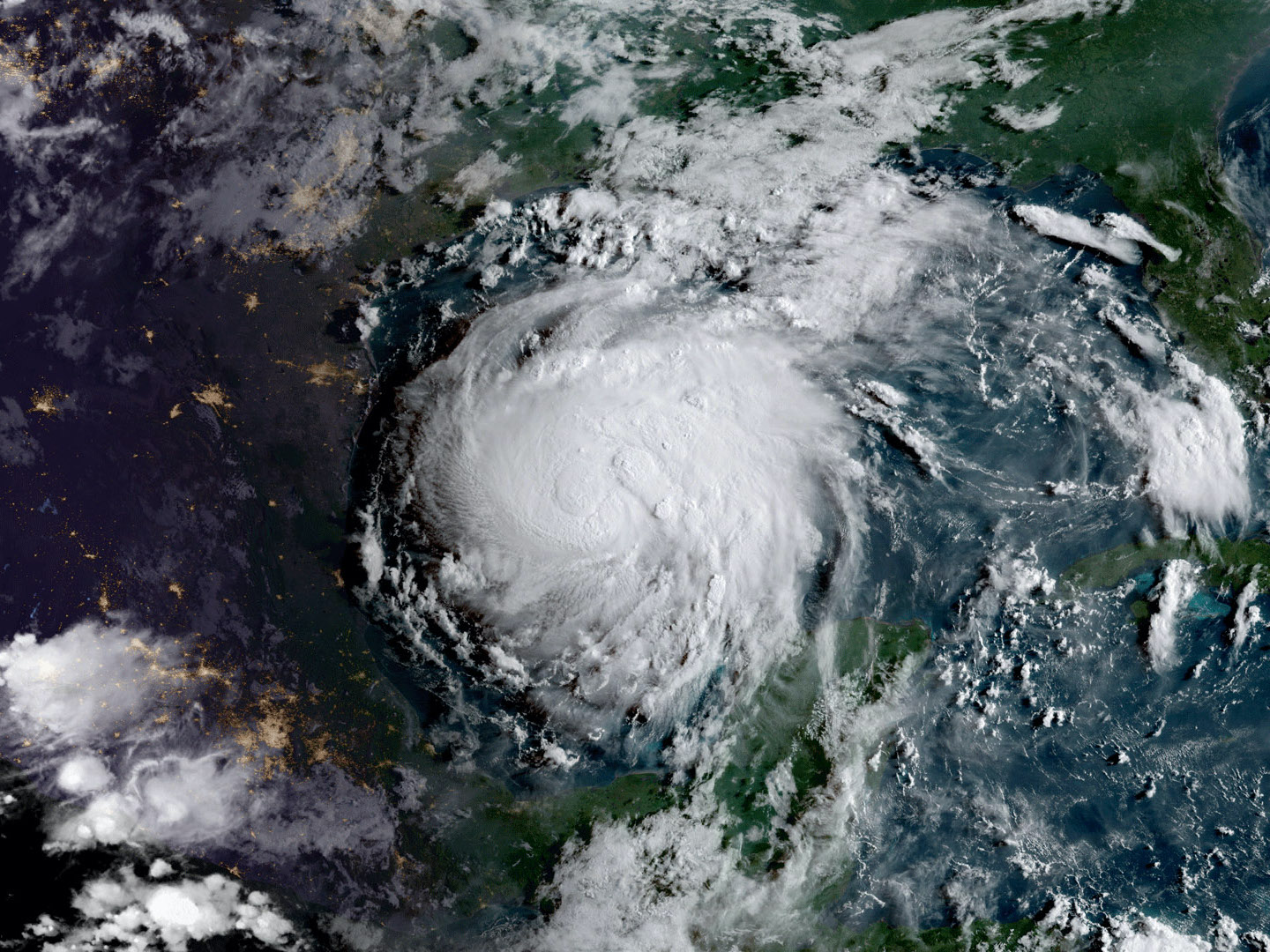

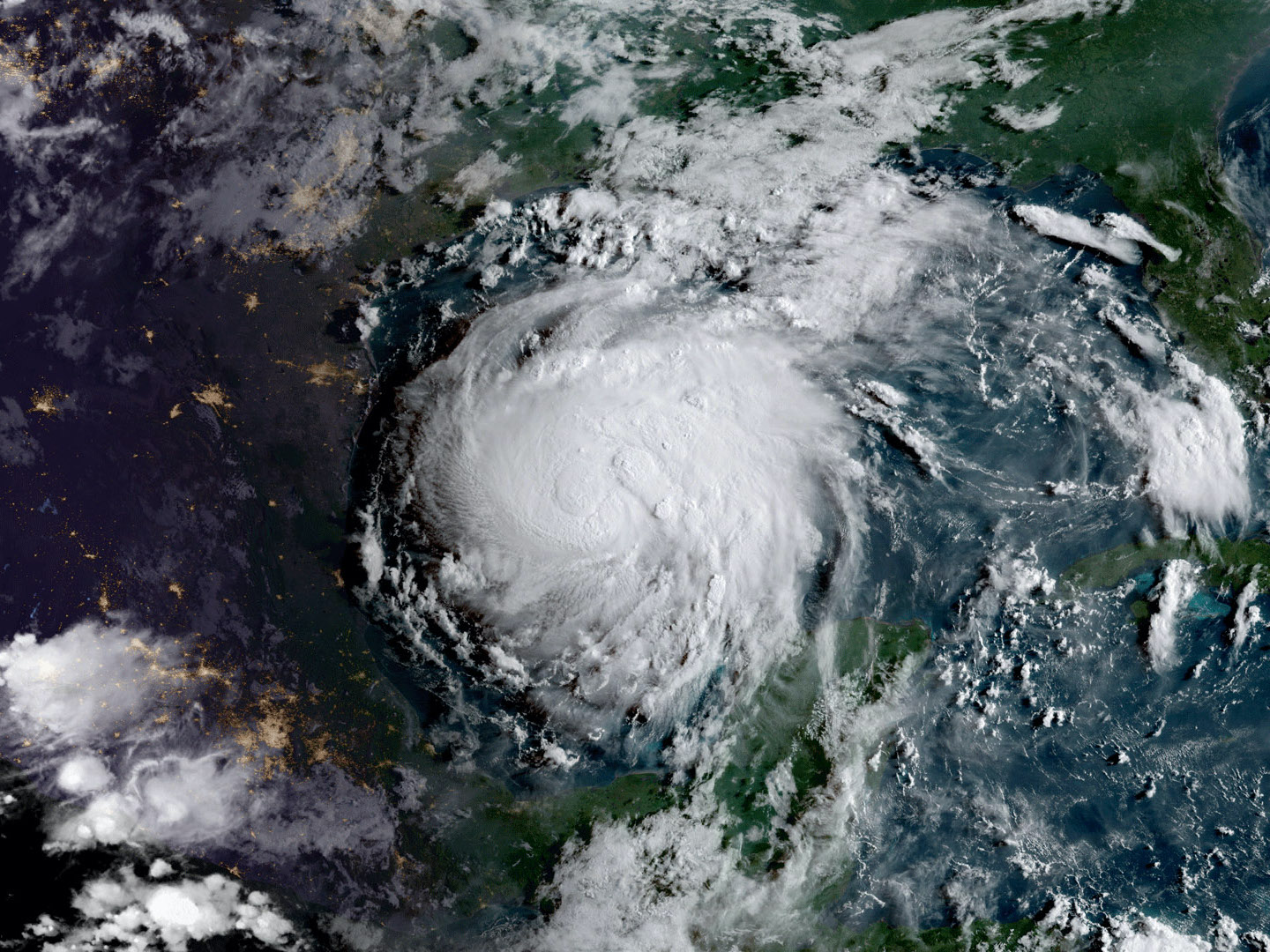

Hurricane Harvey, the wettest hurricane to ever hit the United States, is an excellent example. The 2017 storm “intensified rapidly as it approached the Texas coast, and then it hit the coast and just wandered a bit over the land and over the ocean, just back and forth for several days. In the meantime, basically acting as a conveyor belt, just dumping huge amounts of warm Gulf water onto Houston,” says Hall. “It was the classic stalling pattern.”

When a hurricane slows, it is largely due to the steering winds that direct and propel the vortex. “Hurricanes are like corks being pushed around in a stream,” says Hall. “If those wind patterns themselves stall, slow down dramatically, or change directions rather abruptly, the hurricane will be sort of directionless and it can sit there stalling.”

These weaker winds are also more meandering. Hurricane Sandy in 2012 was propelled by erratic steering winds. “As it was heading up the east coast, instead of swerving back out toward the middle of the Atlantic heading east, which most storms do at that latitude, it took a sudden left-hand turn and hit New Jersey dead-on,” says Hall.

Given how much influence steering winds have over hurricane speed and trajectory, climate change may influence stalling by reshaping large-scale wind patterns. Climate models generally show shifts in these broad patterns, though it’s not exactly clear how much the changes might translate to hurricanes themselves. In a 2019 study, Hall and his co-author Jim Kossin found that North Atlantic hurricanes are more likely to stall near the coast, but did not link this to climate change. The first study linking climate change and slowing hurricanes was published in April by researchers at Princeton University.

This limited research is not yet enough to prove any definite conclusions. “Yes, we’re seeing an observed-slow down. It may not be due to global warming,” says Jeff Masters, a weather meteorologist and co-founder of the Weather Underground. He says in all likelihood research will confirm the link to climate change in the future, even though there’s not enough evidence right now.

To more conclusively attribute this slowing pattern to climate change will require more data. “The historical hurricane record globally only goes back to about 1982 where we’ve got good satellite data,” says Masters. “That’s not very long to generate a climate change attribution study because climate operates on a scale of 30 years or more.”

In the meantime, though, there is a mechanism that could explain why climate change might cause hurricane slowing. “The main reason we’re seeing the weakening of the winds is because we’re seeing a decrease in the North to South temperature difference,” says Francis, an expert on climate change in the Arctic and a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. This is thought to be largely due to belts all along the northern parts of the continents where the snow has been melting much earlier due to climate change. As a result of this shift, she says, “we are seeing the soil heat up much earlier in the spring, which reduces that North-South temperature difference, which is what is decreasing the wind.”

This temperature gradient causes the steering winds and the jet stream to weaken, resulting in many weather patterns becoming effectively stuck for a longer period of time. “So we’re seeing weather regimes of all sorts, whether they’re cold spells or stormy conditions or snowy conditions, all tending to become more persistent,” says Francis. Hurricanes are part of this broader trend of dangerously slowed-down weather.

Even if hurricane slowing isn’t eventually conclusively attributed to climate change, it’s still increasing—and that risk that will need to be communicated. The 1-5 Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, the predominant scale for communicating hurricane risk in the US, only looks at wind speed. By failing to take into account the serious risk of slowing and stalling, along with more rainfall, this metric can misrepresent the true danger of a storm. For instance, when Hurricane Florence made landfall in North Carolina, it was downgraded to a Category 1 storm, only to tragically stall and dump enough rain to break at least 28 flood records.

“We need another scale or some totally different way of warning of a danger,” says Masters. He points to the European warning system as a better alternative. “They just have a yellow, orange and red alert where they describe all the impacts of a storm. A red alert is basically unprecedented; this is going to be worse than anything you’ve ever seen,” says Masters.

This warning system will also need to communicate hurricanes’ increasing intensity, related to the temperature underneath the storm. There is a broad consensus that warming oceans, which reached the hottest temperature on record in 2019, have been increasing the intensity of storms. “When we warm the oceans, we are basically providing more fuel for tropical storms to form and to get stronger,” says Francis. Warmer oceans and air increase the evaporation of water vapor into the air, fueling a more potent storm.

Francis says that focusing on communicating the impacts of storms is the most effective way to convey the danger. “I think that was a big success story for Hurricane Laura because [the National Hurricane Center] described the storm surge as unsurvivable,” she says. “I think a lot of people who were reluctant to evacuate, heard that and were like, ‘Oh, I’ve never heard them say that before. I guess I better go.’ ”