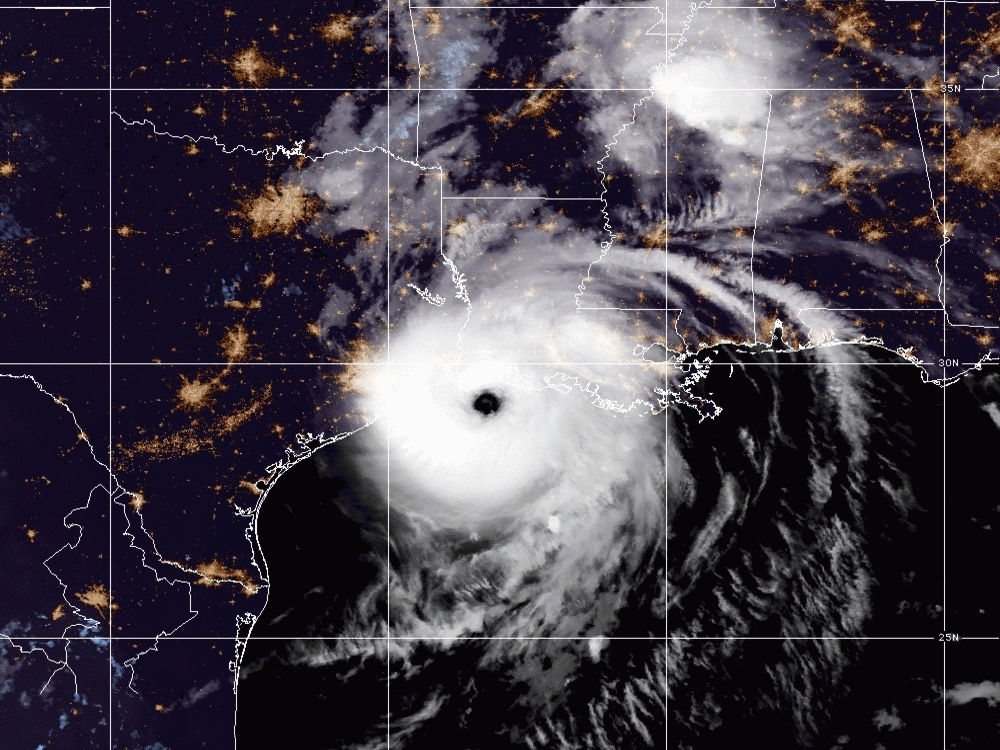

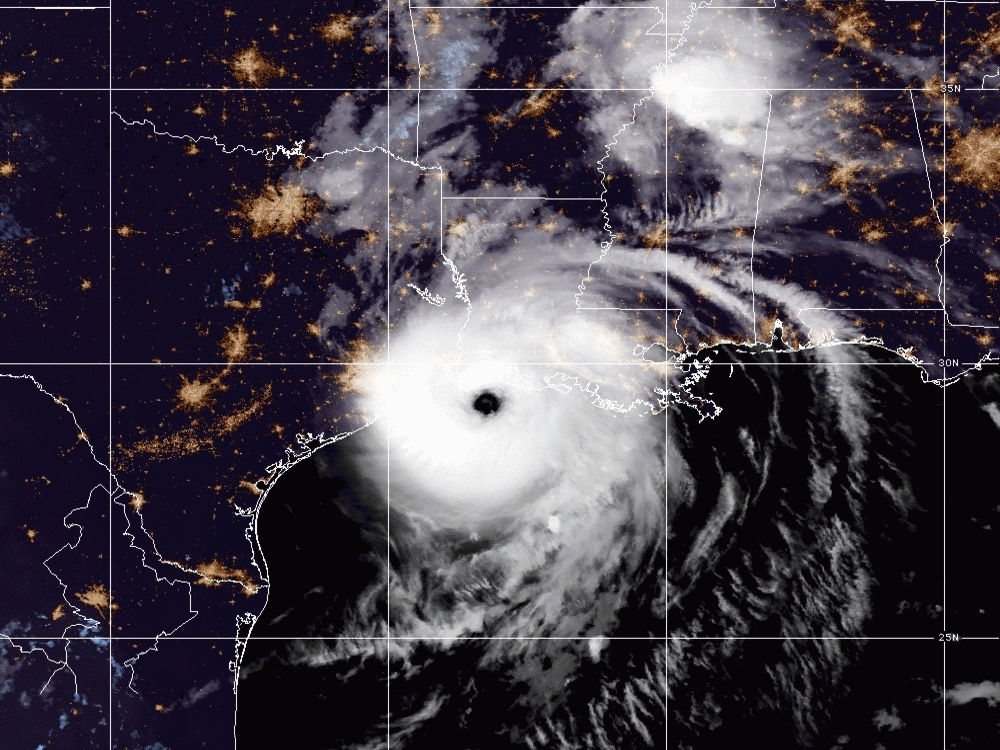

Hurricane Laura made landfall as a Category 4 storm in the early hours of Thursday morning, with winds just a few miles per hour shy of the Category 5 mark. Wind speeds hit 150 mph, tying with a hurricane from 1856 for the strongest storm to ever hit Louisiana. Laura has now been downgraded to Category 2 storm, but it’s still barreling over Louisiana with winds of 110 mph.

The full extent of the damage isn’t clear yet, since the storm is still raging, but there are already massive storm surges recorded and more than 500,000 without power. A chlorine plant near Lake Charles caught fire due to damage from the storm on Thursday afternoon. So far no one has been hurt, but chlorine fumes can be nasty so locals are advised to stay inside their homes.

Meteorologists predicted water levels up to 15-20 feet above ground level, a height at which the National Hurricane Center termed the surge “unsurvivable.” It will likely take days just for the floodwaters to recede.

There were evacuation orders in place for some half a million people across Louisiana and Texas, but as is always the case during severe weather events, some residents were unwilling or unable to relocate.

Evacuations were also hindered by the social distancing requirements in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19. A county spokesperson in Texas said that only 15 to 20 people were being placed on buses rather than the usual 50, and there were concerns about having large numbers of people sheltering in one place.

This is the strongest storm to hit the region in any resident’s lifetime, and the area will be recovering from the storm for a long time. Hurricane Katrina was a Category 3 storm with 125 mph winds, though it still holds the record for most intense hurricane in Louisiana by barometric pressure. Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards told a local radio station that “There will be parts of Lake Charles underwater that no living human being has ever seen before.”

Laura has already killed nearly two dozen people in Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and the death toll is likely to increase in the coming days. Governor Edwards reported the first confirmed US death on Thursday morning, telling reporters that a 14 year old girl had died when a tree hit her home. In total there are six deaths due to the storm recorded as of Thursday night. He has called in the entire state’s National Guard to help rescue people stuck in the storm’s path.

At least 150 people have stayed behind in one parish in Louisiana, and there are doubtless others who could not or would not evacuate. There are a lot of reasons that people stay in their homes when a hurricane hits, and many of them are complex. One crucial factor: money. Housing, fuel, and food during an evacuation can cost a family of four upwards of $2,000. In January 2020, surveys showed that less than half of Americans had $1,000 in savings they could use in an emergency. With tens of millions across the US currently unemployed, the number of residents with anything close to an ample emergency nest egg has likely dropped even lower. The median household income in many of the affected Louisiana parishes is below $50,000, with poverty rates upwards of 15 percent.

Leaving behind pets can also seem like an insurmountable hurdle for others, and though legally shelters are supposed to provide care for pets, not all actually do. Other people have loved ones with disabilities—or disabilities themselves—that makes it hard to leave, either because it’s physically a challenge or because they worry a shelter won’t be able to meet their needs.

Yet another reason: people don’t have experience with these types of storms. Many folks who have lived in the area for a long time are likely to recall prior storms that they weathered just fine, and figure they can survive whatever the next one brings as well. Sociologists estimate that people remember the worst effects of a hurricane for just seven years, and that 85 percent of US coastal residents haven’t actually experienced a direct hit from a major hurricane before.

While the extent of Laura’s impact still remains to be seen, you may already be wondering how you can help some of the people affected. The best course of action, according to people who research natural disaster responses, is to donate money, not things—and to send that money to local organizations rather than large non-profits. Smaller organizations are more likely to know what their community needs and to stick around for a long time after the disaster. They’ll also know exactly what supplies they need and won’t want to grapple with the tons of items that well-intentioned people send to the area. You can also look for local businesses you can support from afar, or see if you can volunteer for a non-profit like the Red Cross.

With the ongoing pandemic, physically flying to the region might not be the smartest or safest choice, especially when resources are already limited to support the people whose homes have been destroyed. If you can’t donate money, you could try donating blood or helping out with fundraising efforts for a local organization. The impulse to help is wonderful—so make sure you put it to good use.

This post will be updated periodically as more news on Hurricane Laura comes in.