Popular Science’s WILD LIVES is a monthly video series that dives like an Emperor penguin into the life and times of history’s noteworthy animals. With every episode debut on Youtube, we’ll be publishing a story about the featured beasts, plus a lot more fascinating facts about the natural world. Click here to subscribe.

Feature Creature: Of Sooty Shearwaters, Bird Brains, Bad Acid, and Alfred Hitchcock

In the Santa Cruz Sentinel, August 18, 1961, there is an account of thousands of birds raining down from the sky at 3 a.m.—crashing into homes and cars in Capitola and Pleasure Point, California just off Monterey Bay. Eight persons were reported bitten. This is the bird: Ardenna grisea, the sooty shearwater.

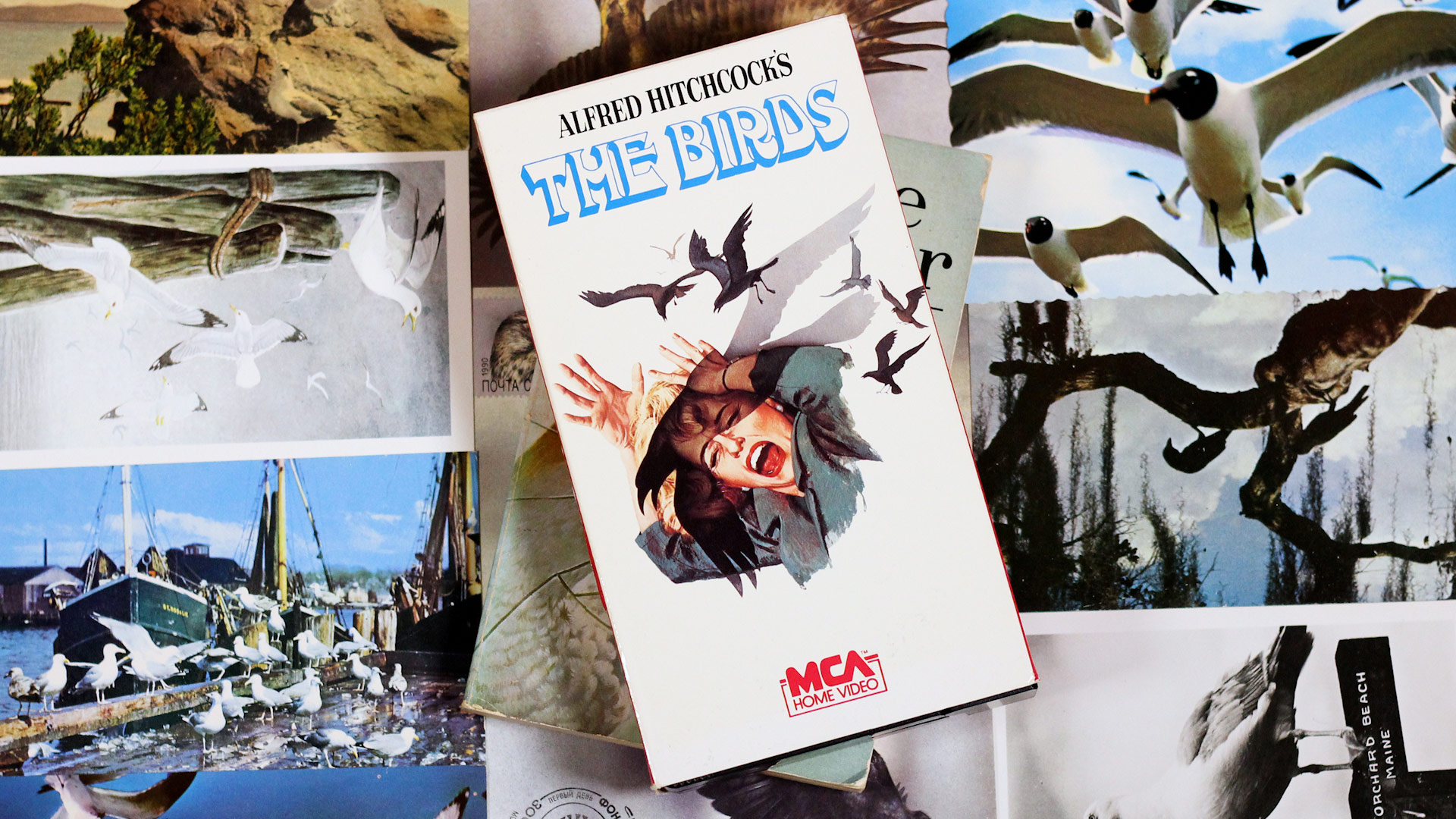

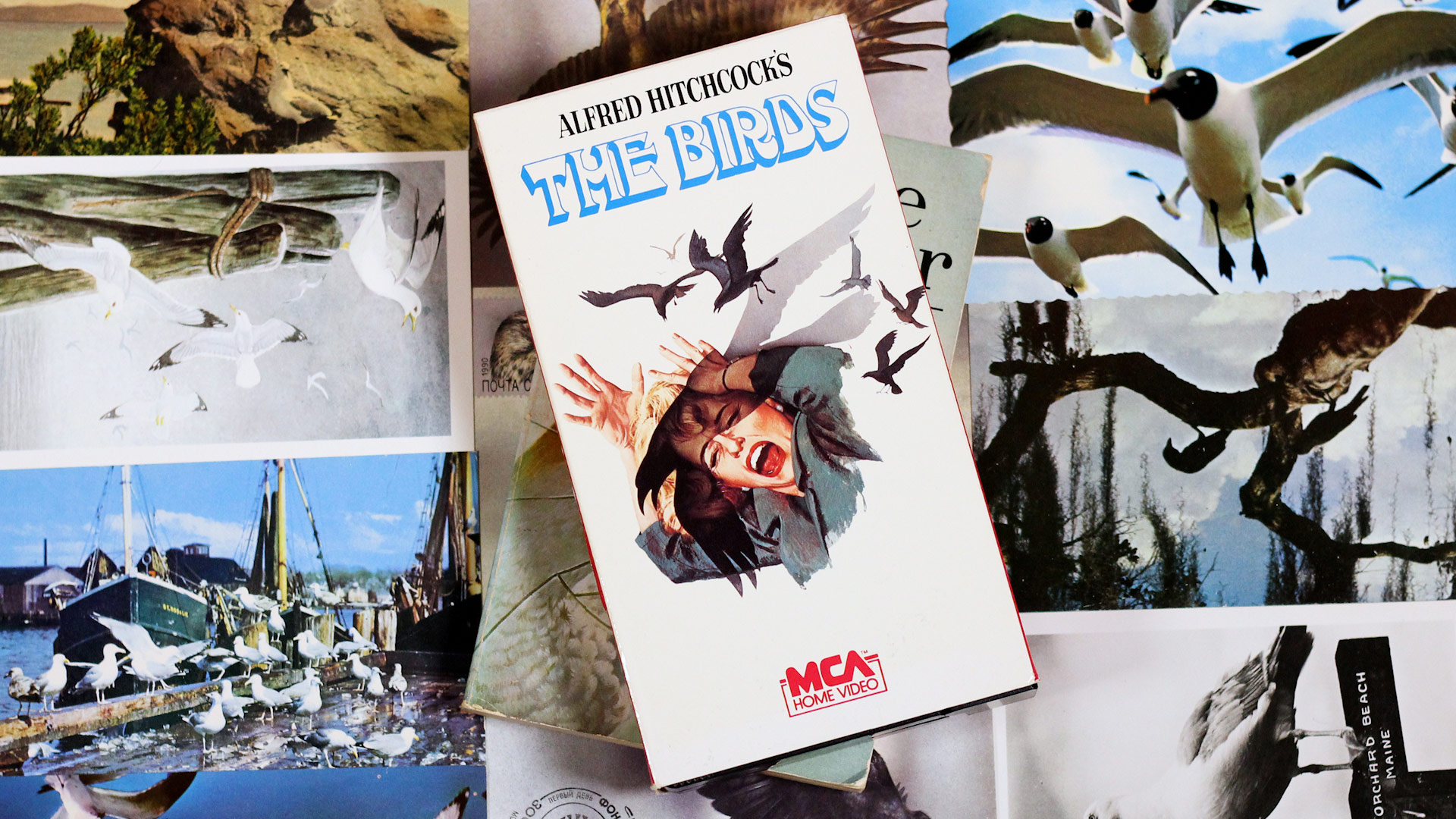

“The word of the bird invasion spread fast throughout the state,” notes the article, “and a phone call came to The Sentinel from mystery thriller producer Alfred Hitchcock from Hollywood.” He requested a copy of that day’s paper. After all, the famed director was adapting a particular 1952 Daphne du Maurier story into a screenplay on the subject of killer birds. And less than two years later, Hitchcock’s The Birds premiered.

Prevailing theories at the time supposed the sooty shearwaters got lost in the fog. But if flocking birds were easily confused in low visibility, which is pretty normal up and down coastal California, then shearwater invasions would be as common as passing rain. So, in order to understand what happened, first you need to know how a flock of birds—like thousands of shearwaters—fly and move together.

Boids of a feather, flock together

Ancient Romans said the gods guided flocking birds. At the turn of the 20th century, learned scientists considered “natural telepathy” or a “group soul” as a flock’s compass. In other words, magic. Which is still sort of true, because have you ever seen starlings fly? Their murmurations are surreal.

Unlike a flock of geese where there’s an obvious leader (imagine a flying “V”), any bird in a flock cluster—like what starlings or shearwaters fly in—can move in any direction and the others will follow suit. That’s because flocking birds aren’t just aware of their immediate neighbor; they’re focusing on the small group of birds around them—up to six or seven of them. The effect has been described as a chorus line, one leg kicking after another.

In 1986, programmer Craig Reynolds made a three-dimensional flocking algorithm, which played out in an early computer animation. He called his flying creatures, “boids.” Three simple steering behaviors guide them:

- Input 1, coherence: fly close, to the other boids.

- Input 2, separation: don’t run into your flock mates.

- Input 3, alignment: match the speed and direction of the boids around you.

This math basically plays out in nature each time a flock takes flight. Now consider if a fourth input was introduced to the flock of boids—a piece of malware instead of a computational rule. That’s what happened to the sooty shearwaters.

Bad acid

Edna Messini, proprietor of the Venetian Court Motel on the beach at Capitola in 1961, wrote about the day the birds came:

“Struggling to the door, I was awed at the sight of hundreds of birds—all with the cry of a baby. They were heavy with sardines unable to fly and lost in the dense fog as they came in from the sea attracted by our lights. They slammed against the building, [regurgitating] fish blood and knocking themselves out. Our manager phoned me, asked what to do? She knew it was the end of the world, panic set in, sure it was germ warfare.”

“Heavy with sardines” and “regurgitating fish blood” are two curious observations. The sooty shearwaters seem more sick than lost.

Thirty years passed, until: in the Santa Cruz Sentinel, September 15, 1991, there is another account of confused birds in Monterey Bay. The bird: Pelecanus occidentalis, the brown pelican. Also, some cormorants. There was no hail of birds like the incident in ’61—they simply washed ashore—but the pelicans exhibited similar symptoms. This time, scientists determined the cause: domoic acid poisoning.

What is domoic acid?

Domoic acid is a neurotoxin that can be produced by several species of Pseudo-nitzschia, a microalgae that flourishes in nutrient rich warm water and low wind. What happened is, domoic acid infiltrated the food chain, making its way into plankton, then anchovies, then the brown pelicans. And when the neurotoxin passes through the blood–brain barrier in birds and mammals, it can cause confusion, disorientation, seizures, coma, even death.

So when domoic acid incidents became more common in the 2000s—more brown pelicans, more cormorants, and even sea-lions—dots throughout history started to connect.

Dr. Sibel Bargu Ates, a biological oceanographer and professor at Louisiana State University, along with a team of researchers, thought maybe the dots went as far back as 1961. In 2011, they analyzed the gut contents of archival zooplankton specimens sampled from the same location and time period as the sooty shearwater frenzy. And, they were full Pseudo-nitzschia fragments, the microalgae that produces the domoic acid toxin. Meaning the food chain was more than likely contaminated.

So, the sooty shearwaters didn’t get lost in the fog. They were—dun, dun, dunnnn—poisoned! The fact they flock together in the thousands—and all fed on krill or sardines tainted by the toxic microalgae—is what made that fateful night feel like the end of the world.

Other Notable Animal Invasions

- In 2003, a research team observed a single female moon jellyfish in Tokyo Bay releasing 414,000 planulae, or young jellyfish, over a 7 day period. That’s another way of saying there are a freaking ton of jellyfish in the ocean. In the mesopelagic alone—the upper 200 meters of the ocean—there are 83,775,659,630 pounds of jellyfish worldwide. In fact, depending on where you live, you may be able to blame jellyfish for a power outage. For as long as there have been power plants that use ocean water for cooling, there have been jellyfish clogging intake pipes—even forcing shutdowns. For example, in 1989, four million jellies were removed from a nuclear facility in India. In 2013, a massive power plant was shut down in Sweden. Unfortunately for jellyfish and humans alike, this is a fairly common occurrence.

- Referred to as “Albert’s Swarm”—because a guy named Albert saw it—the largest known plague of locusts descended on Nebraska in 1875. The swarm of Rocky Mountain locusts covered 110 miles of land. Based on estimations, that means there were likely 3.5 trillion insects blanketing the area for five days. Old Al described the phenomenon as if it were the size of the Milky Way. Perhaps the biggest shock of all: less than thirty years later this particular locust species went completely extinct.

- Frognadoes and fishnadoes. You know how a tornado transports killer sharks in that incredibly horrible and not even particularly funny Sharknado movie? Something like it is possible. There have been accounts of waterspouts—tornadoes that form over open water—sucking up all kinds of creatures and depositing them elsewhere. There aren’t a lot of reports of actively raining animals, but the aftermath has been witnessed several times, including frogs in Kansas City and Dubuque in the late 1800s, frogs in Siberia in 2005 and fish in Louisiana in 1947 and Australia in 2010. But are cownadoes possible?

Popular Science’s Encyclopedia of Bird Facts

Tubenoses

See that little hole on the Great Albatross’s beak? Well, birds in the order Procellariiformes—albatrosses, petrels, shearwaters—are commonly known as tubenoses because of that curious little characteristic. These external nostrils on their bills is what gives them incredible senses of smell. Tubenoses can locate their nest burrows by scent and are even able to detect a whiff of plankton while on the wing. Plus these birds all drink saltwater and excrete the salt through the tubes. This is what largely enables Procellariiformes to spend the vast majority of their lives out at sea. One downside: because they rarely come to land, they are pretty awkward walkers.

Early flights didn’t go so well

About 160 million years ago, two tiny dinosaurs known as Yi qi and Ambopteryx longibrachium glided through the trees in present-day China. Unfortunately for Yi and Ambopteryx, these aerial abilities were pretty underwhelming, scientists reported on October 22. The researchers examined soft tissues preserved in a fossil specimen of Yi and used mathematical models to simulate how both dinosaurs would have glided. They found that the bat-like dinosaurs would have been clumsy gliders and probably went extinct because they couldn’t compete with the keen flying abilities of birds and early mammalian gliders. Read more about the early fliers, this way. >>

Dance of the Ostriches

The mating dance of the male ostrich is, simply put, one of the most ridiculous, over-the-top, feel-like-you-might-die funny occurrences on planet Earth. Just see for yourself. Also, this. Now, the only way to describe it is to ask you to imagine the dance floor at a wedding. Now, picture that guy. You know the one—shirt only half buttoned, a glistening glow of dance sweat, the confidence of General MacArthur in demanding all eyes on him while a song that was cool five years ago plays. Of course, that guy is not flexible at all. So any movement is committed with the whole body—meaning a shoulder roll is a roll of the body entirely. This is how a male ostrich performs his mating ritual.

Why do they dance like this? (Ostriches, that is—not that guy.) Well, it’s all about attracting a mate. Hilariously, female ostriches go for it. During their breeding season, which spans March or April to September, males’ necks and legs become redder. The change in color is because their bodies are flushed with blood. In most subspecies, pairs mate in private, but the South African ostrich mates in front of any other females that might be around.

The act of matting is a fast affair, too. The female sits, the male mounts her from behind, and two or three pumps later the show is over. Males have been observed fleeing the scene afterwards like a bank robber when the alarm is tripped.

Three billion birds lost

In Hitchcock’s The Birds, the amateur ornithologist Mrs. Bundy is sympathetic to the avians. In what’s probably a forgettable line for most, she provides a possible motive for why the birds attack. She says, “Birds are not aggressive creatures… It is mankind, rather who insists upon making it difficult for life to exist on this planet.” Indeed, if you watch a short trailer Hitchcock produced to advertise his film, you might start to think maybe humankind was asking for it.

More than 50 years later, there’s this sobering headline from Popular Science: We’ve lost almost 3 billion birds in the U.S. and Canada since 1970. That’s about 29 percent of birds that once lived in those countries.

Undoubtedly, habitat loss is playing a big role in the decline of birds. Toxic chemicals may also be a driver. In fact, another study found that sparrows eating seeds coated with a neonicotinoid insecticide commonly used in agriculture lost weight and then delayed their migration. Other threats include windows, light pollution, and domestic cats. Read more about declining bird populations, this way. >>

Subscribe to WILD LIVES on YouTube for more wild stories about animals like The TRUE STORY of Hitchcock’s The Birds