Fossils can tell scientists a lot about prehistoric life, but they can’t say everything. When it comes to understanding our animal and plant forebears, there’s a lot we’ll probably never learn from fossils, like what colors ancient animals were. However, in rare cases, researchers get lucky. In a new paper published in the journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, by a team of researchers at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology, the group identified the true colors of three ancient insects that were preserved in amber—an incredibly rare find for paleontologists.

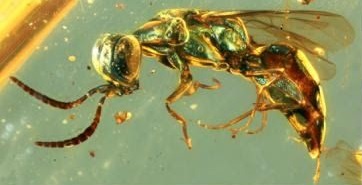

The insects can be dated back to the Cretaceous period, which occurred 99 million years ago. The animals were all preserved in pieces of amber from a mine in northern Myanmar. The insects—a beetle, a fly, and a wasp—are so well-preserved in the amber that their true color could be identified.

“The way that the color is preserved in these things is really remarkable,” says James Lamsdell, a University of West Virginia paleobiologist who was not involved in the research. “There have been reports of color in the fossil record before, but often what we’re looking at is not the true color, because it’s been changed by the fossilization process.”

In instances where the color is questionable, Lamsdell says, scientists gather clues from the cellular structure of the exoskeleton and extrapolate what the color probably was. But in this case, the iridescent “structural color” of these insects remained visible after the researchers prepared the specimens, a process that involves carefully polishing the amber until the insect bodies are nearly exposed, and in some cases setting it against a light. Blue, green, and purple iridescent colors are all clearly visible in the specimens.

The researchers say these images were edited in Photoshop “to adjust brightness and contrast” but that the colors themselves were not changed or edited. The iridescent structural hues of these very distantly related species is notable, Lamsdell says, since they seem to have each evolved iridescent traits independently at some point before these specific insects were born. Although scientists can speculate as to what evolutionary pressures drove all these different insects to iridescence, there’s no way to know for sure.

Frustratingly, this is where the story ends for these shimmering insects. The oldest amber in the fossil record appears about 320 million years ago—not too long ago on the geologic timescale. And the amber in Myanmar is all from the same specific time in the Cretaceous period. That means there’s no way to trace the evolution of these iridescent traits back further in time.

Remarkable as they are, the results are tainted for Lamsdell by knowledge of what it likely took to get the amber in the first place. So-called “Burmese amber” is mined in Myanmar’s Kachin state, which in prehistoric times was thickly forested with coniferous trees that produced sap which turned into amber, perfectly preserving numerous examples of the insects of that place and time. Today, that amber can be mined. “It’s ended up being a resource for fueling conflict,” says Lamsdell, “because it’s very lucrative.”

Mining amber is a big, ethically questionable business in Myanmar, as Josh Sokol documented for Science in 2019. And awareness of the ethical issues has grown in recent years. This April, representatives of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology signed their names to a letter asking the editors of scientific journals to stop accepting and publishing papers whose findings were based on Burmese amber.