Deep at the bottom of the Gulf of California there lies a graveyard. Scientists have discovered dozens of squid carcasses being gobbled up by scavengers in the waters of northwestern Mexico. The bodies appeared fresh, hinting that many more vanished from the seafloor before they could be spotted. If so, squid graveyards could be the sites of much-needed feasts for bottom-feeders around the world, the team reported recently in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

It’s not easy for deep-sea critters to get enough food to survive. Lots of marine snow—tiny bits of dead animals, feces, and other debris—does drift down to the seafloor. But it sinks so slowly that microbes devour much of the nutrients before it arrives. Corpses, on the other hand, sink too quickly to decompose much before they touch down. While squid flesh has been found in the bellies of deep-sea fish, though, actual bodies are almost never seen—until now.

The scientists did not set out to find a graveyard. But the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) they sent to explore the seafloor kept stumbling upon dead squid. “As we saw yet another dead squid…we realized—hey, this isn’t random, there’s a pattern here,” Bruce Robison, a deep-sea biologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in Moss Landing, California, said in an email.

Over the course of 11 dives between 2012 and 2015, the robotic submersible found the remains of 64 squids and egg sheets, the membranes that females use to encase their eggs. On one dive, it observed 36 carcasses and egg sheets.

The squid all belonged to the Gonatidae family, whose members are plentiful in the Pacific Ocean. As in most species of squid and octopus, females enjoy but one breeding season before dying when their eggs hatch. The squid were probably drawn to waters near the graveyard because the area offered ideal conditions to hunt or hide from predators while brooding their progeny. Then, after pouring all their energy into the developing eggs, the females perished and sank to the seafloor.

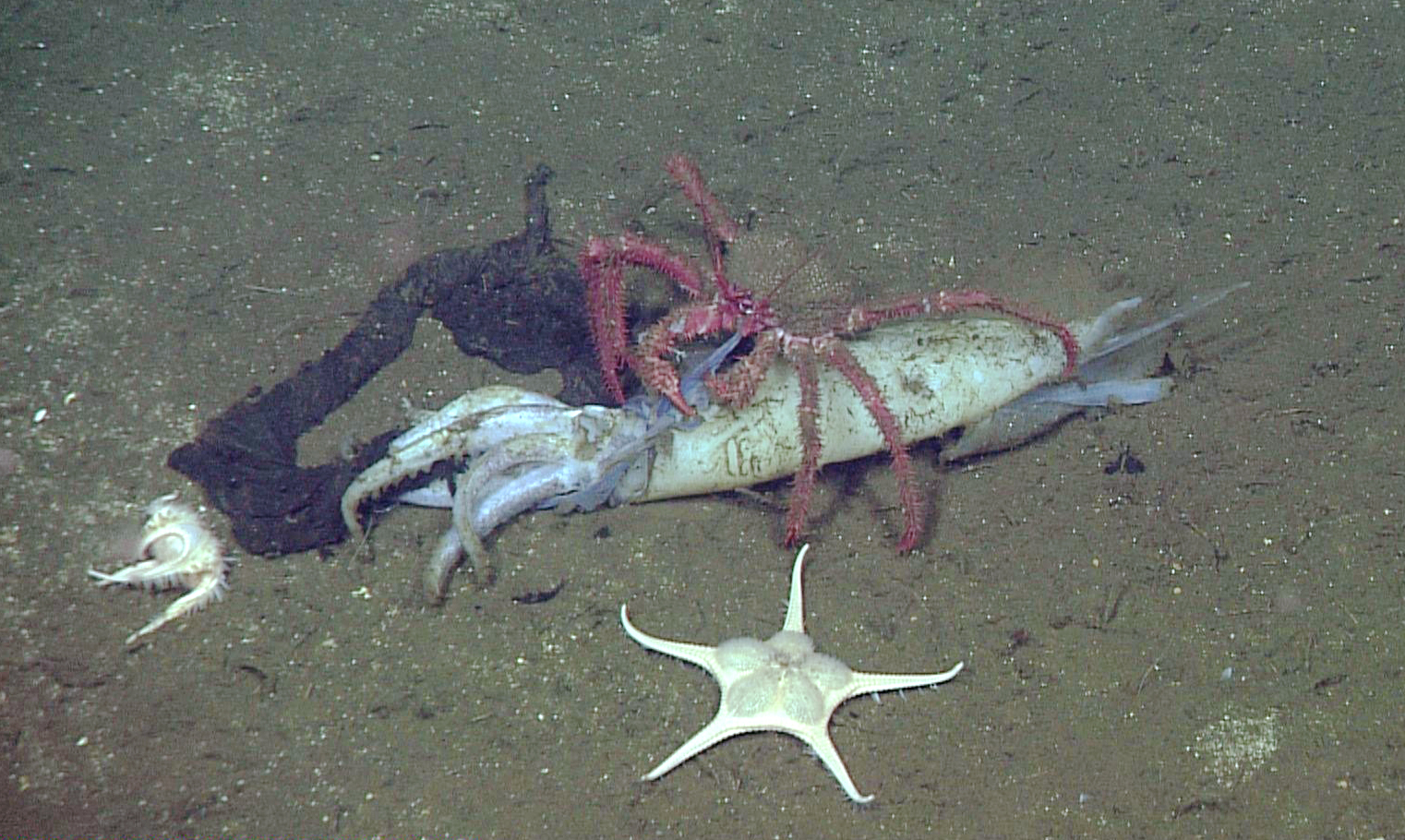

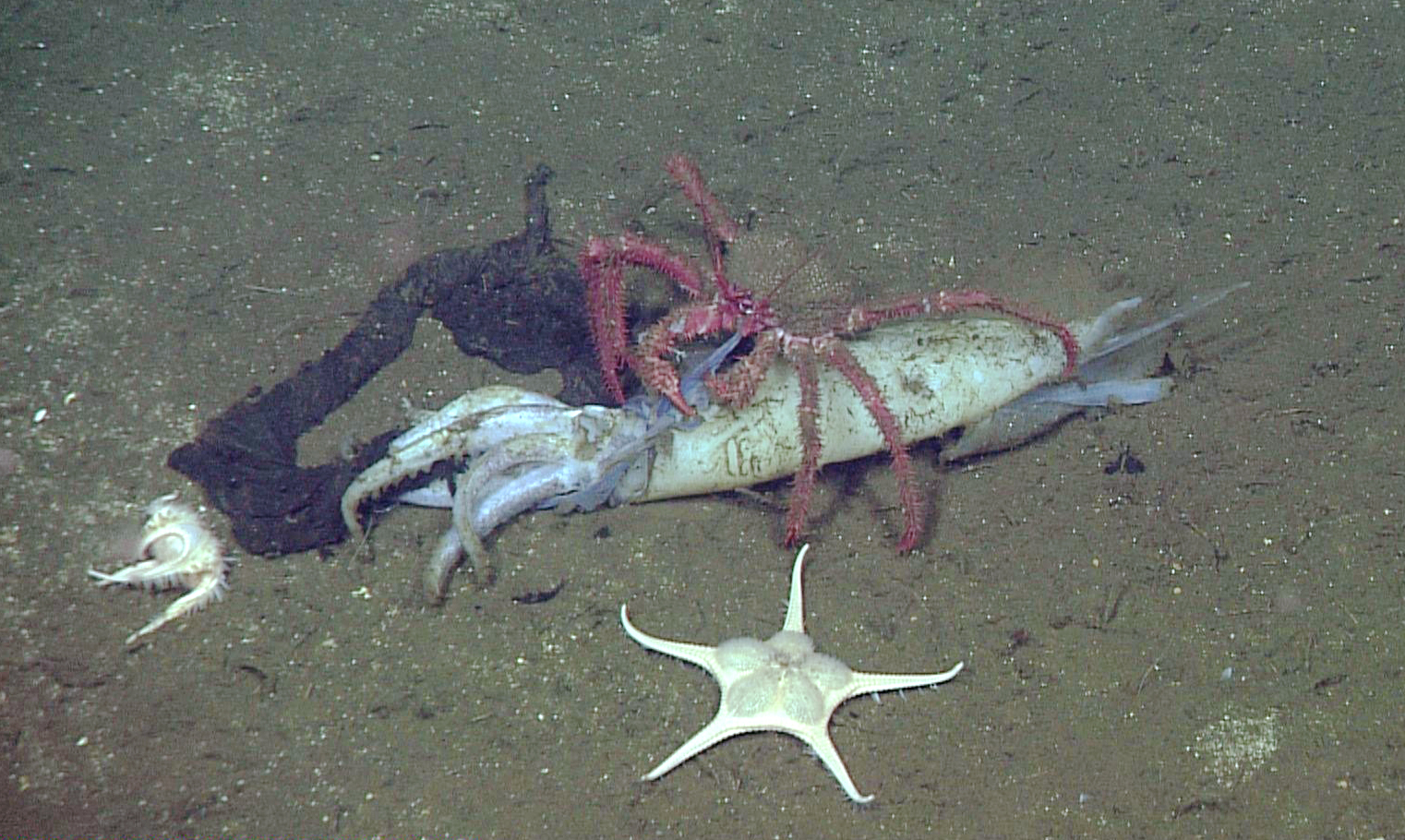

It’s likely that the squid had died recently. Living squid control their coloration by expanding and shrinking pigment-containing cells called chromatophores. After death, the cells contract one final time, leaving the body ghostly pale. Several of the squid carcasses bore purple patches, though, indicating their chromatophores were still active.

The carrion was swarming with ratfish, worms, sea stars, sea cucumbers, and other animals. It takes years for these scavengers to make a large whale carcass disappear, but they can likely manage a squid within a day. “Food this rich does not last long on the deep seafloor,” Henk-Jan Hoving, another member of the team and a deep-sea biologist at the GEMOAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel in Germany, said in an email.

In future, he and his colleagues hope to investigate where else squid graveyards show up on the seafloor and how many species contribute their remains. The researchers suspect, however, that these fleeting graveyards can be found worldwide. And, because there are massive numbers of squid in the seas and they don’t live very long, dead females could add up to quite a few meals for scavengers.

Squid populations are on the rise because their predators are being overfished, and they are better equipped to adapt to climate change than many marine animals, the researchers say. This means squid may transport even more carbon to the seafloor in future.

The deep sea is the largest ecosystem on Earth, and also the one that we know the least about. Squid graveyards are a reminder, though, that the bottom of the ocean is not an isolated world, and its inhabitants are influenced by what happens in the waters above. “The fact that we continue making important new discoveries like this about the basic processes of deep-sea ecology shows that we have a great deal yet to be learned,” Robison says.