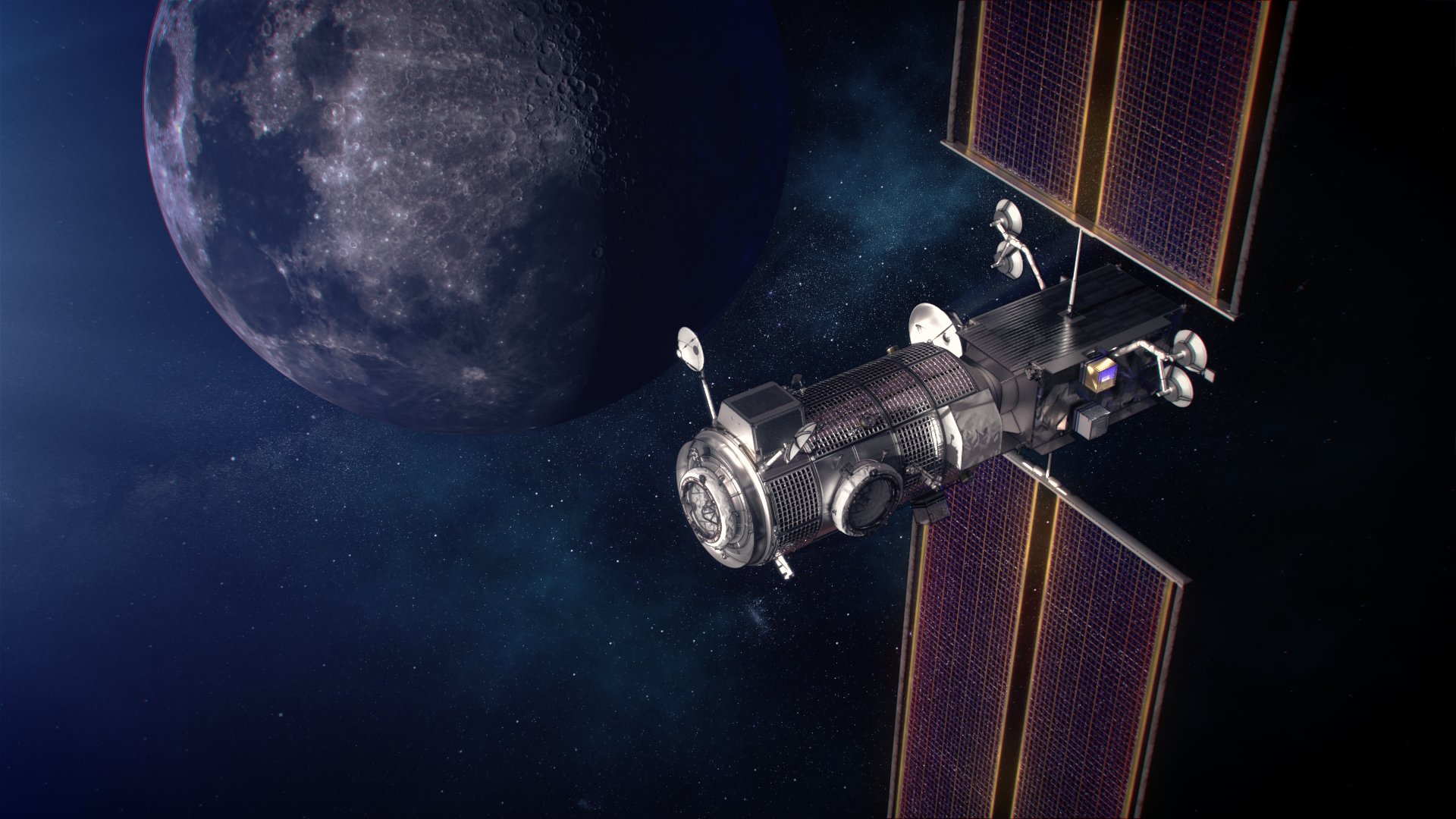

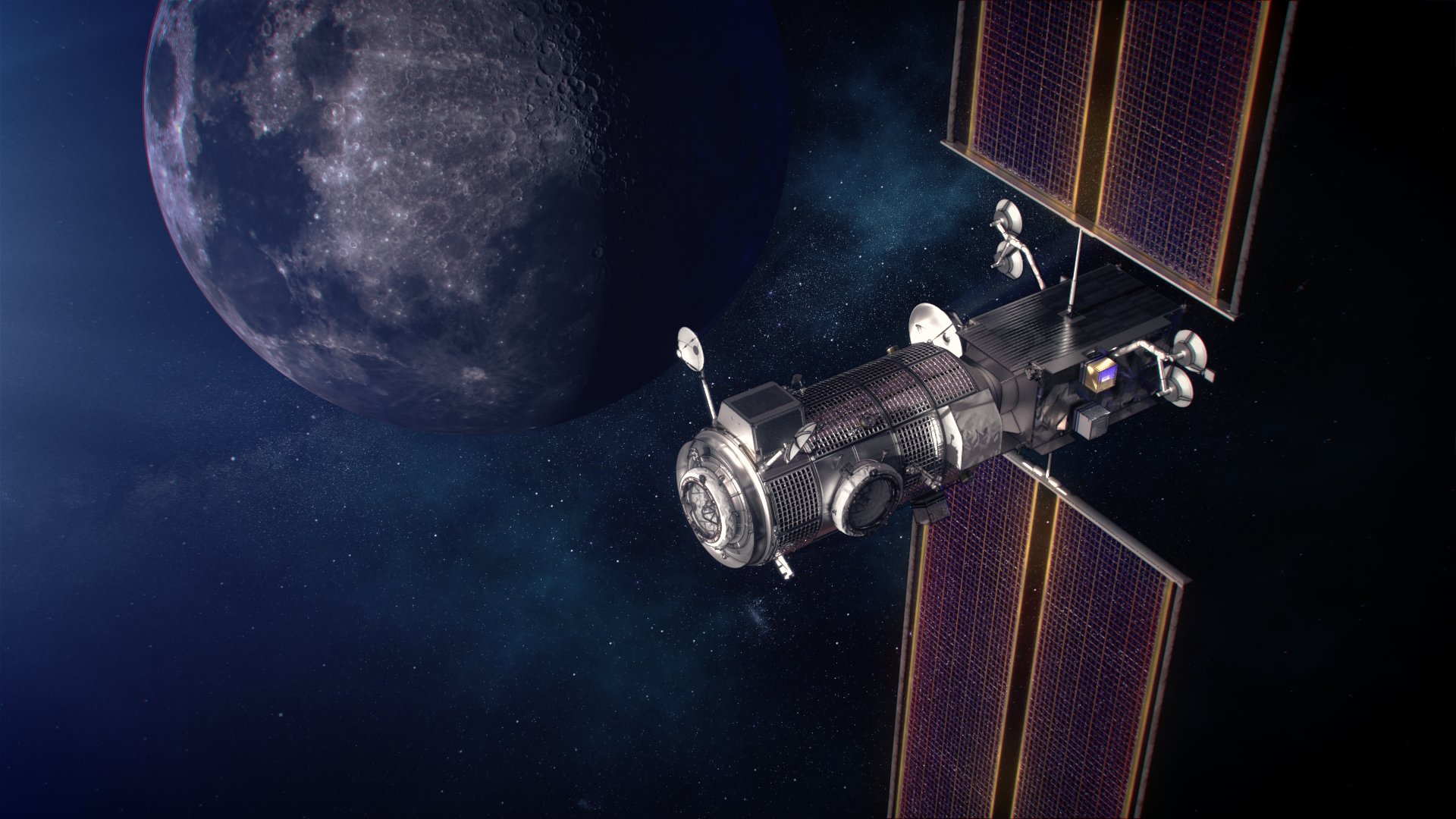

Launching sometime in the next decade, NASA’s Gateway—a lunar outpost where Artemis astronauts will live and work as they orbit the moon—will help conduct in-depth science operations vital to humanity’s continued exploration of deep space.

One such mission, called Hermes, or the Heliophysics Environmental and Radiation Measurement Experiment Suite, has recently passed a critical mission review, and NASA scientists will now transition into finalizing the mission’s design.

“Hermes will be a critical part of the Artemis mission and NASA’s goals to create a permanent presence on the moon,” Jamie Favors, Hermes program executive at NASA, said in a press release on January 30.

Built by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Hermes is one of two mini-weather stations that will monitor space weather with a focus on heliophysics, the study of the sun. The mission will examine dynamic conditions created by the sun, such as coronal mass ejections (CMEs) that can cause harm both to mission instruments and human activity.

[Related: NASA is testing space lasers to shoot data back to Earth]

The station will be made up of four specialized instruments that will be placed together on one platform. One of them, called Nemisis, or the Noise Eliminating Magnetometer Instrument in a Small Integrated System, will measure the magnetic fields surrounding Gateway.

Getting a better grasp on space weather phenomena through this mission will be helpful in preparing for future crewed expeditions. “In terms of human exploration, space weather is really about the radiation environment,” says William Paterson, project scientist for the Hermes mission.

Scientists have been measuring space weather fluctuations on small scientific spacecraft for decades, but Hermes will be the first monitoring system on a crewed mission to gather data outside of Earth’s magnetic field—which acts as a radiation shield. This magnetic field, which extends about 60,000 miles into space, protects astronauts and the International Space Station from harmful radiation spewed out during events like solar flares and other galactic cosmic rays.

But as the moon orbits around the Earth, it passes in and out of the planet’s magnetotail, part of the field that is swept back by solar radiation. To get there, Hermes will have to fly through the Van Allen Belts—big swathes of energetic charged particles trapped by the Earth’s magnetic field. In lower orbit, astronauts aren’t usually affected by these belts, but if they were to fly at a higher altitude, this radiation could prove fatal over an extended period of time.

Gateway will spend a quarter of its time inside this protective shield, giving researchers a rare opportunity to study and directly measure radiation from the sun. After launch, it will take about a year for Hermes to get into the right position to start its mission, which, if the journey goes as planned, will take place right after the peak of the sun’s current solar cycle.

“Looking at the activity coming from the sun, it’s gonna be a really good time to get there and start doing our mission,” Paterson says.

In a separate payload, Gateway will also carry Hermes’ counterpart, ERSA, short for European Radiation Sensors Array. Both Hermes and ERSA were named after two of the goddess Artemis’s half-siblings in Greek Mythology.

Although Hermes’ measurements will be used to ensure astronaut’s safety, its data is primarily scientific. On the other hand, the main focus of the European Space Agency’s ERSA will look at how solar wind radiation affects astronauts and their equipment.

The daily data these stations send back will help create a clearer picture of how space weather operates around the entirety of our solar system. That information is especially important to know as humans venture towards creating habitable environments on, or near other planets.

“We see this as kind of a pathfinder to help establish this capability that we think is going to be needed in the future to support exploration,” says Paterson.

Hermes still has a long way to go before the scheduled liftoff in late 2024, giving ample time for the mission to undergo tests and changes. But Paterson is looking forward to the data that will be collected.

Because most research into heliophysics is usually done in isolation, Paterson is interested in seeing this project expand humanity’s knowledge of how our star’s unique dynamics affect the rest of the solar system.

“I think we’re going to be able to do really great science from the Gateway,” he says. “There’s going to be a learning curve to figure out how to work around some of those challenges, but we’re pretty confident.”