If a black hole devours a planet and no one is around to hear it, does it still make a sound? Physicists and astronomers have been trying to map astronomical data through sound for decades—and now we can finally listen to a black hole scream into the void.

Earlier this month, NASA released the first recordings, or sonifications, of what two black holes sound like—and it’s just the kind of noise astronomers and science fiction buffs were expecting: eerie, ethereal, and aurally extraordinary.

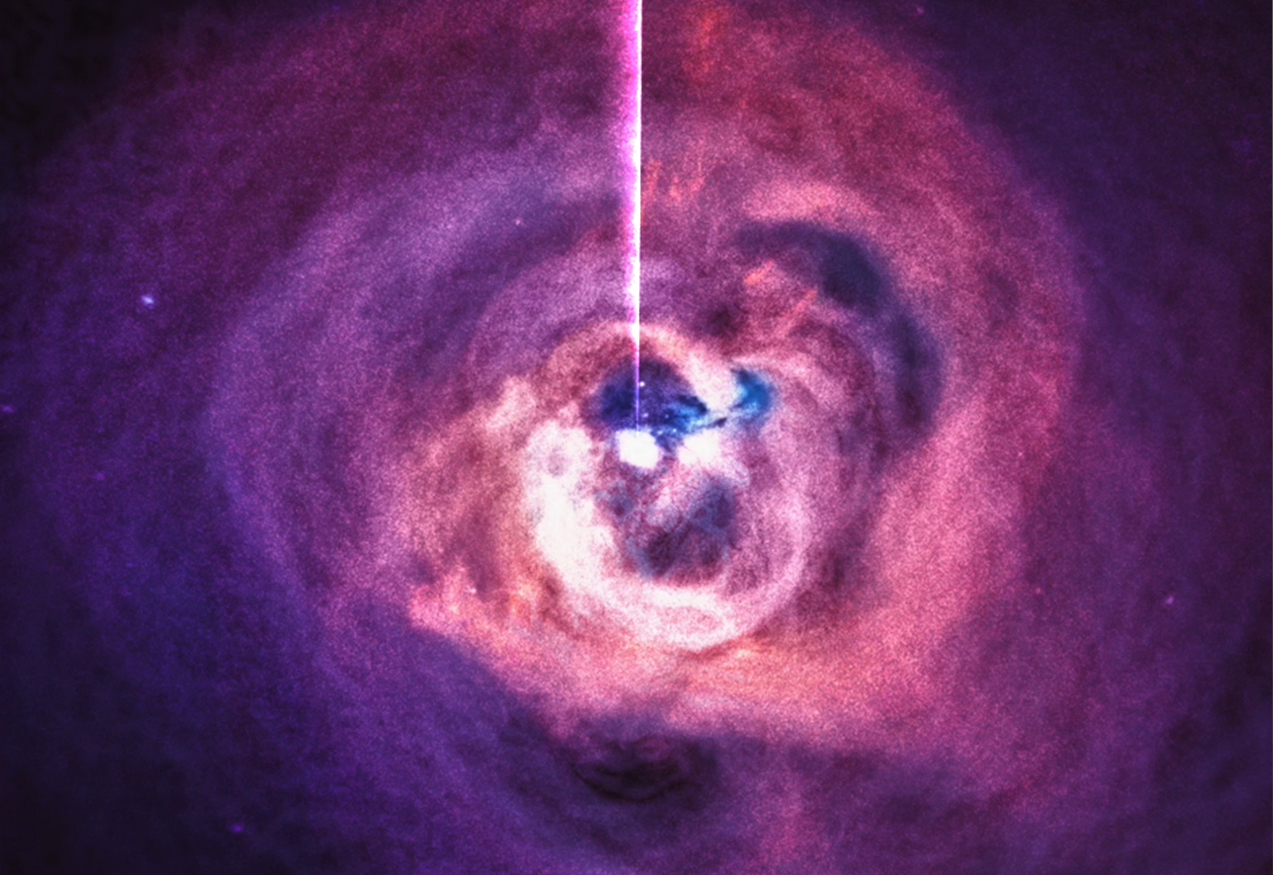

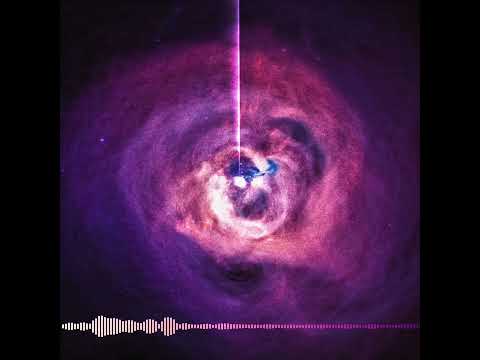

The universe is rife with the hum of celestial melodies—but it’s only relatively recently that humans have developed the technology to be able to hear them. A team of scientists at NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory were able to extract and make audible previously identified sound waves from a nearly 20-year-old image of the Perseus galaxy cluster—a collection so full of galaxies, it’s assumed to be one of the most massive objects in the universe. It’s one of the closest clusters to Earth, around 240 light-years away.

“This sort of bespoke method is really about extrapolating something new out of this archival information,” says Kimberly Arcand, the visualization scientist for NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory who led the research. Translating scientific data into acoustic signals has also become vastly easier in the past few years. For example, scientists can create parameters for all kinds of numerical data by assigning those values to higher or lower pitches, or vice versa, to turn them into musical notes.

These short sonifications typically take a few hours to create, but with the right data, can be completed using sound engineering software and other publicly available computer programs, like Python.

The team’s finished result reveals a deep magnetic groaning created by a “supermassive black hole causing [a] rippling in its surrounding environments.” The radar band sweeping over the image in the video above allows the listener to take in what the ripples sound like from different directions. But Perseus’ original notes are pitched so low (about 57 octaves below middle C) that they exist outside the range of the human ear. This meant that the researchers had to resynthesize its signals by scaling them upward from their true pitch. Arcand’s team also used this technique to turn the recent Event Horizon Telescope image of Sagittarius A*, a supermassive black hole that lies at the center of our own Milky Way, into sound as well.

“There are a number of areas in astrophysical research specifically where there’s really big data, or really noisy data,” Arcand says. “Having a human sense of hearing can be an excellent way of picking that good data out.”

But besides listening to the ghostly ringing of black holes, turning data into sound can also assist astronomers in exploring the universe outside our cosmic neighborhood, particularly in humanity’s rush to discover new exoplanets.

“In some cases, there are real musical rhythms and patterns in the cosmos,” says Matt Russo, an astrophysicist and sonification specialist who is a colleague of Arcand’s. “Bringing that to life, I think really helps connect something that’s very abstract and technical, with something that’s very personal and familiar, which is music.”

[Related: What your voice would sound like on other planets and moons]

After scientists discovered that the star Trappist-1 was the most musical solar system in 2017, Russo went on to co-found SYSTEM Sounds, an outreach project that translates the rhythm of the universe into beautiful, unearthly tones that expresses both sonic data and artistic pieces. The project has since produced regular sonifications in collaboration with NASA, and Russo himself has helped create many of the pieces featured in an entire album that utilized Chandra’s observations, called A Universe of Sound.

“The connection between music and astronomy has gone back to Pythagoras over 2,000 years ago,” he says. “But lately, there’s been a huge explosion of sonification in general, especially in astronomy.” While data sonification in astronomy is a relatively new development, scientists have a long history of using sound to communicate all kinds of information and data.

“The beauty of sonification is there are many stories to tell.”

— Matt Russo, astrophysicist and sonification specialist

For instance, Geiger counters are devices used to warn humans of the dangers of nearby radiation levels, and relay that information by employing sounds like rapid clicks and popping noises that oscillate, depending on the level of radiation it detects. This month, researchers also made recordings of auroral sounds in an effort to prove that the aurora borealis, or the northern lights, are present even when invisible to the naked eye.

But unlike other scientific processes, creating music from data often comes down to perspective as well as artistic expression. “The beauty of sonification is there are many stories to tell,” Russo says.

And just like written stories, sonification can help people connect to places and entities far beyond our reach. Transforming celestial objects into sounds allows those with vision loss to experience these images.

One member of the blind and partially sighted community, Christine Malec, works with the SYSTEM Sounds project to improve the accessibility of their sounds. She often tests and gives feedback to help the scientists create sonifications that have different elements, often commenting on individual notes, or an entire piece’s pitch and tone. Until she first heard these celestial sounds, astronomical phenomena were merely abstract words and ideas.

“When I heard my first sonification I had goosebumps,” Malec says. “It was a visceral, sensory experience that I’d never had before with astronomy.”