The World Trade Center memorial sits in the bustling heart of New York City. But standing at the edge of the cataracts, cloaked in a man-made forest of swamp white oak trees, the sounds of urban life fade away. Designed by architect Michael Arad and landscape architect Peter Walker, street life and city clamor is suppressed by the roar of two man-made waterfalls, 30 feet deep and pumping 26,000 gallons of water a minute.

Where the twin towers once stood tall, acre-sized reflection pools now dip deep into the Earth. Opened to the public on the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, the site is austere, contemplative, and expository, in keeping with other modern memorials. The gaping fountains are forged from black granite; their perimeters lined with the names of the dead. But in one way the site breaks from tradition: it serves not only the eye, but the ear.

“If you think about traditional memorial, they are big stone things. They are monotone. The only experience a visitor has is what they see,” says Lester Levine, who compiled a selection of the 5,000-plus site proposals into the book 9/11 Memorial Visions. While fountains have always offered some variation—none more so than the waters at World Trade—Levine says, “other than that, they are silent, they aren’t colorful, and they don’t move.”

Sound design has been slow to trickle into other spaces of collective remembrance, due to tradition and technical challenges. But this Sunday, the world’s largest wind chimes will ring out at the site of the Flight 93 crash in western Pennsylvania for the first time, marking a subtle shift in the way we memorialize tragedy.

The Statue of Liberty is conspicuously silent. The Vietnam War Memorial is cut from cold, quiet stone. And the Lincoln Memorial doesn’t tell lies—or anything else. But the tragedy of Sept. 11, 2001 was an undeniably sonic experience. In the days after the attacks, tapes from the cockpits of hijacked planes and voicemails left by loved ones moments before the towers collapsed emerged. Sirens wailed and fighter jets scrambled overhead. Radio journalists and artists lugged around recorders, ready to save the stories of those who survived. For many, proper memorialization of the day’s events required sound in kind.

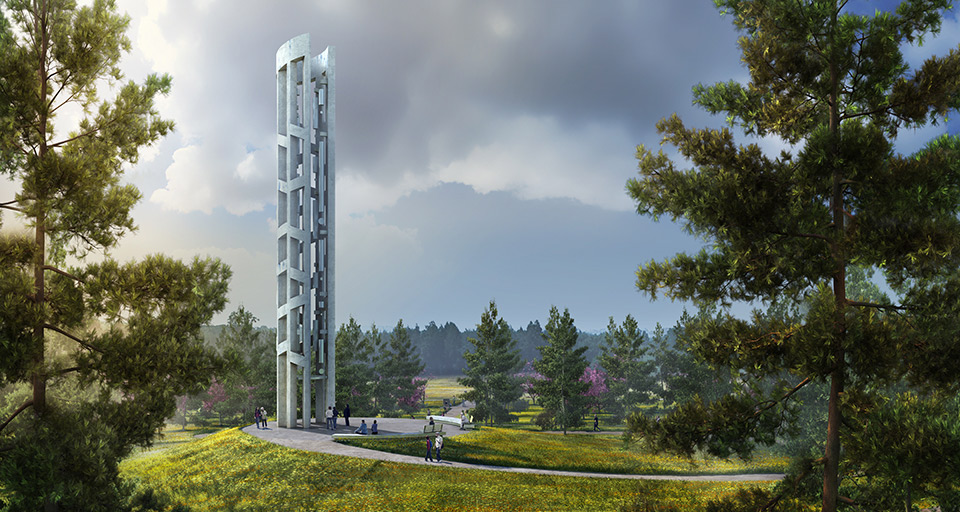

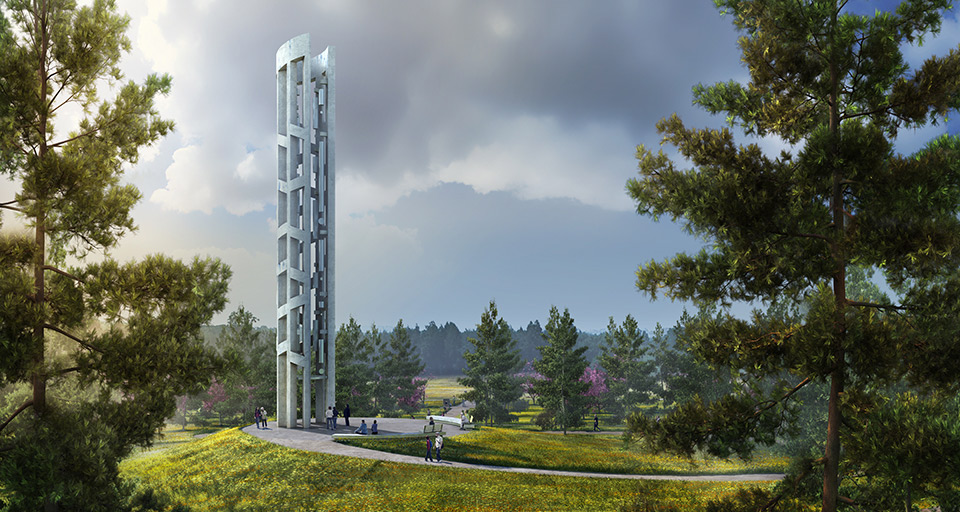

Architect Paul Murdoch, the mind behind the Flight 93 National Memorial, says it’s the voices of the 40 passengers and crew members aboard the downed United Airlines plane that linger with him. That’s why his proposal for the 2,200-acre National Park Service-operated site called for not one but two phases. First came the Wall of Names, etched in white marble. Now, the Tower of Voices, a 93-foot-tall precast concrete structure with 40 of the world’s largest chimes.

“It starts with the wind,” says Elizabeth Valmont, an acoustics expert at the design firm Arup and acoustic lead for the chimes. The tower stands sentinel over the site, she says, with 40 independent polished aluminum chimes, between 5 and 9 feet in length, nestled within. Each chime represents an individual aboard the flight, and together they engage in an eternal “conversation,” but only as the currents guide them.

Driving along the highway that hugs the site, or standing in the memorial field itself, the musical apparatus is beautiful, commanding, and deceptively simple. The process kicked off more than two years ago, Valmont says, when Murdoch reached out to Arup about conducting a few simulations in their state-of-the-art sound lab. This is standard operating procedure: before starting the expensive and time-consuming work of construction, architects often model their proposed designs using computer programs, miniature modules, and prototype tests in order to ensure their vision will work in the real world. “But therein lies the most challenging part of this project: How to make an internal striker work,” Valmont says.

Most chimes, like the ones hanging in your backyard, sound off when some a force, like wind or a human hand, pushes the thin tubes against an external striker. That collision is what creates cascading waves of sound. But Murdoch’s vision for the Tower of Voices required each chime to have its own steel striker inside. “Having a chime work like a bell, where there’s a hammer inside the tubes, had not been tested before,” Valmont says.

They conducted feasibility studies in the lab, with the goal of finding the ideal location for the strikers, the weight of each element, and the optimal materials for the chimes. But “you can only do so much at your desk,” Valmont says, so her team headed into the desert to test early iterations of the design in a more realistic environment. In a 2017 test in Simi Valley, they found that their internal striker prototypes worked as anticipated, whirring to life under local wind conditions.

But before any chimes made their way to Pennsylvania, plans and prototypes passed through many other hands. A musician created a tuning table, ensuring each chime has a distinct sound, but there’s harmony among the group. A dedicated chime consultant weighted in. A fabricator created the final product, testing the chimes himself along the way. Wind consultants added their two cents on the fluid dynamics of the site. And contractors brought the tower to life. “There’s never been a memorial quite like this,” Valmont says. “And certainly there hasn’t been one so audible.”

Memorials remain primarily visual experiences. But there are signs that sound is on the rise. In 2014, Maya Lin, who won the competition to design the Vietnam War Memorial at age 21, designed a “sound ring” for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. What looks like an empty frame for an oval painting and turned it is actually a wood-clad speaker system, memorializing extinct and endangered bird species and their ecosystems. Meanwhile, the design competition manual for the National Native American Veterans Memorial stated explicitly that “use of multi-sensory design elements, such as incorporation of sound or light, is permissible.” The winning proposal, designed by Harvey Pratt and slated for completion in 2020, appears to be a strictly visual memorial. But the guidelines nevertheless reflect a shift in consciousness, however small.

Styling a suitable sound for the Flight 93 memorial chimes was a long and arduous process. But Murdoch seems certain it was worth the struggle. While most memorials are unchanged from the day they open up to the public, “through sound and wind activation, it becomes a living memorial, in the sense that it is always changing,” Murdoch says. And while other designs provide one shared experience, the tower will ensure that every visit is unique, even personalized. “There’s an emotional aspect to memorialization where tapping into different sensory experiences can be very valuable,” he says. “It’s offering yet another type of commemoration.”