The life of a modern inventor is a lot like you’d imagine it.

“Most ideas… I say it out loud, and I go, ‘Woah. That’s really bad,'” says Scott Amron, the mind behind Amron Experimental, a small product development lab in New York. “A lot of times, I have to say it to somebody to hear how bad it is, or how good.”

The product designer, who has been categorized as everything from an electrical engineer to a conceptual artist, caught the world’s attention in 2012 when his toothbrush-fountain hybrid appeared in The New York Times. The second generation of the design, which is available in pre-order for $12, pushes tap water through the toothbrush and into a perfect liquid arch that a brusher can easily slurp up. The brush heads are easy to replace with a snap-in, snap-out function to reduce waste. “No changing hands to cup water,” the product’s design page boasts. “And, no more putting your head in the sink.”

In recent years, Amron has continued his work as a consultant with companies as varied as Victoria’s Secret, the homeware company OXO, and the toy company Skip Hop. He’s also continued to refine his passion projects in the lab, from fashioning a key that’s also a ring (or a carabiner) to creating a coffee sleeve that swells in response to heat, among other inventive designs. Throughout it all, Amron’s been guided by his resource-conscious aesthetic. “Really the goal is to take something [companies are] already making,” he says, “and just trying to make it do more with less.”

Lately, he says, he’s been largely consumed by two major products: a fresh take on the fruit label, and an alternative to coffee stirrers.

Most stickers are made of plastic, an adhesive (typically a pressure sensitive one), and ink. Some are cute, like the stickers kids earn for their kindergarten achievements. Others are useful, like barcode stickers that allow for a swift supermarket checkout. Unfortunately, all of them are a source of waste. Polyvinyl chloride, a synthetic polymer often used as the face of a sticker, slowly decays from exposure to the sun and other elements. And produce stickers—like the ones on apples—can cause their own unique problems. “For composters, these labels are really a big deal, Amron says. “They say it’s the worst contaminant in their entire chain. It gets stuck in filter, in waterways, it’s a contaminant. It’s bad news.”

Around 2011, Amron formalized his creative solution to this sticky problem: Amron’s Vanishing FruitWash Labels. In its current incarnation, Amron’s prototype is a little sticker-like circular label with the requisite barcode and four-digit call number. But it does away with the plastic, because the label is made of hardened fruit wash. When a customer adds water to the label, it acts as a cleaner to scrub an apple clean, sloughing off pesticides, dirt, and other contaminants as you go.

The trick is turning Amron’s eco-conscious prototype into a commercially-viable replacement for current produce stickers. “The produce industry is so large,” Amron says. “The scale is [such] that everything has to be perfect to work.” In earlier versions, for example, users had to scrub furiously to turn the sticker into a wash. But if Amron made the material too easy to dissolve, there’s a chance the stickers would come off in transit, and never make it to the supermarket . After more than seven years, Amron says, “I think we’re really close.” He hopes to see every day apple eaters using the vanishing fruit wash labels by the end of 2018.

Difficulties haven’t dimmed Amron’s enthusiasm. He says all of his projects start with problems. The solutions come later. “It’s nothing but problems and you keep solving them until it’s good enough to be better” than anything else on the market, Amron says. That’s how Amron got stuck on coffee stirrers, those thin sticks people use to mix their coffee and other drinks.

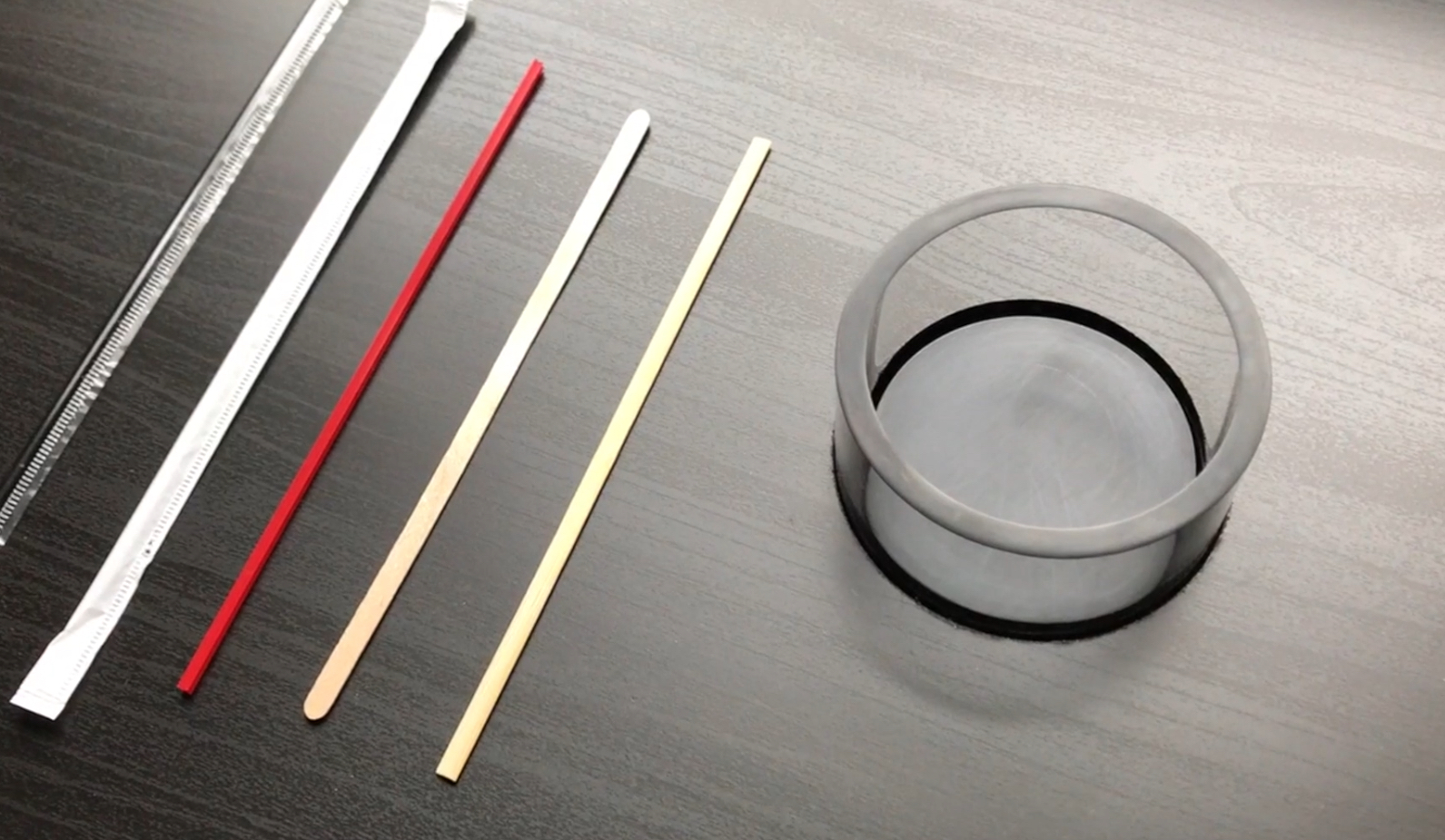

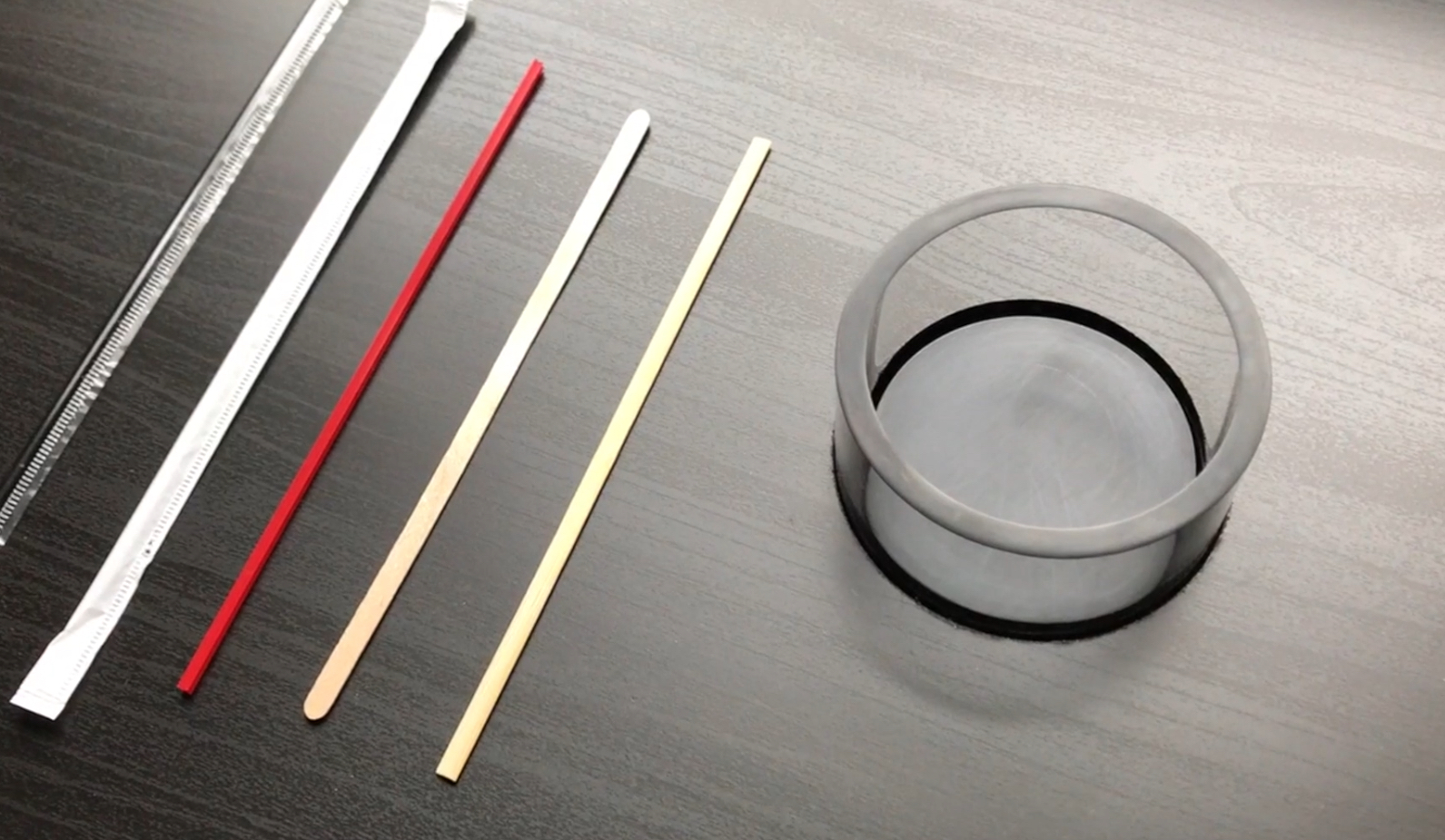

Every day, millions of swizzle sticks are used once at cafes and coffee shops around the world and discarded. Some plastic sticks get recycled, and a portion of the wooden ones end up in compost, but most hit the landfill. Even if the materials in these stirrers are reused, they require the manufacturing of harmful synthetics, or the harvesting of hundreds of trees. Enter the Stircle.

Earlier this year, Amron began selling his mechanical beverage stirrer, the Stircle, for $345 a pop. Handmade in his Long Island lab, the device, which can be built into a table, is a small polycarbonate plastic receptacle, which Amron tested to ensure can fit everything from a Dunkin Donuts cardboard coffee container to a Starbucks plastic cold brew cup. When a barista puts a cup in, the base of the Stircle carefully jostles the drink to ensure added sugar, pumps of flavor, and shots of coffee are evenly distributed. “It stirs better than most people stir,” he says.

Amron estimates that the device will be efficient, able to handle 50,000 drinks on a mere 10 cents of electricity. He also designed it with an emphasis on durability. It has an estimated 10 year lifespan, compared to less than 10 seconds for a typical wooden stir stick. When the motor eventually runs out, the Stircle will have another life through recycling. “It’s made of recyclable materials,” he says. “The motor is the only thing” destined for the garbage bin. “Plus it’s fun, it’s novel, it’s fun to watch,” Amron adds.

For now, Amron says he’s focused on bringing his current inventions to customers, eschewing new ideas in favor of refining the tools he’s already brought to life. But when he takes on a new project, whether it’s months or years from now, it’s sure to entail many more artsy responses to overlooked problems. “I’m always searching for the Holy Grail of inventions. A perfect invention would be something that’s cheaper to make, uses less materials, [and] is better for the world all around,” Amron says. “Some people, their only goal is to improve the bottom line. That’s not the Holy Grail. That’s business.”