Obesity is our century’s version of the Kennedy assassination: Everybody’s got a theory. But even with blame perpetually shifting — one day it’s fast-food corporations, the next it’s genetics — and a $40-billion-a-year diet industry, our waistlines just won’t stop expanding.

The prevalent belief is that the problem is merely a matter of willpower. If we could only acquire some, the thinking goes, we’d be able to eat less, move more, and maintain a reasonable weight. It’s a position backed by common sense, of course, but it’s also the kind of oversimplification that could be the reason we’re not coming up with any lasting solutions. “There’s a sense about obesity that we already know all the answers,” says David B. Allison, a biostatistician at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

But in truth we’re only just beginning to reveal them. Faced with a mounting collection of research implicating unconventional factors like viruses, pollutants and the amount of sleep we get, even the National Institutes of Health has begun to explore alternatives to traditionally held beliefs about weight gain. “We realize that obesity is more complex than we thought, so it’s necessary to explore all possible theories,” says Jerrold J. Heindel, the health science administrator for the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, a division of the NIH.

Weird as they may seem, the following hypotheses are quietly transforming the way we think about and treat obesity.

Artificial Sweeteners Make Us Fatter

THEORY

Sugar substitutes may blunt the brain’s natural ability to measure calories, causing us to overeat.

EVIDENCE

On the surface, it makes sense that America’s consumption of products made with no- or low-calorie sweeteners would increase at about the same rate as incidents of obesity — after all, don’t zero-calorie sweeteners go hand-in-hand with dieting? They do, but perhaps not in the way you might think. “Most people have assumed that as people gained weight, they increased consumption of artificial sweeteners,” says neuroscientist Terry Davidson of Purdue University. “Our data suggests that [the cause and effect] could go the other way.”

Davidson and his colleague, psychologist Susan Swithers, published their findings last February in the journal Behavioral Neuroscience. They fed rats either artificially sweetened yogurt or sugar-sweetened yogurt in addition to their normal rodent chow. The animals that ate artificially sweetened yogurt not only gained more weight, they also appeared to lose their natural ability to keep track of the extra calories and eat less later on.

“It’s a Pavlovian approach to obesity,” Davidson says. “Animals learn to use taste to predict caloric consequences, and in nature, sweetness is almost always an indicator of calories.” When we experience a sweet taste with no accompanying caloric intake, it confuses that calibration tool. Repeating that experience, as in drinking a diet soda every afternoon, might actually deprogram your calorie-counting mechanism for good. (In the rats, effects were seen in as few as 10 days.)

FRINGE FACTOR

Moderate. Even skeptics admit that the evidence is compelling, but causality has yet to be proven in humans. And although rats have similar taste receptors as us, they have a more limited diet and don’t respond to all sweeteners the same way as humans do. (The Purdue study focused on saccharine, one of five artificial sweeteners approved by the Food and Drug Administration and one that rats do register like us.)

NEXT STEPS

More study is needed.

We All Came Down With A Bad Case of the Fat

THEORY

Love handles are contagious. Viruses lurking in your food may spread obesity, infiltrating adult stem cells and transforming them into fat cells.

EVIDENCE

Back in 1988, when Nikhil Dhurandhar was a doctoral student at the University of Bombay, thousands of chickens in India were inexplicably dying. Dhurandhar’s curiosity was piqued by the strangely plump carcasses that the afflicted birds left behind. Nearly 20 years after he identified the lethal adenovirus that caused the epidemic, Dhurandhar and researchers at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, part of the Louisiana State University System, announced the startling news that they had pinpointed another strain, known as Ad-36, that increases fat in human tissue. How the virus spreads is still unknown, but Dhurandhar suspects that you can get it from contaminated food.

He and Richard Atkinson of the University of Wisconsin tested more than 500 people for the presence of Ad-36 antibodies, an indicator of infection, and found that infected people weighed more than non-infected people. Earlier studies in rodents and chickens showed that even when infected and uninfected animals ate the same amount, only the former became obese. And they stayed obese for up to six months after the initial infection, which suggests that you may not be able to bounce back from “infectobesity,” as Dhurandhar terms it, the same way you can from, say, a stomach virus.

FRINGE FACTOR

Scarily enough, the theory is gaining acceptance. It might sound far-fetched to think that love handles can spread like the flu, but research bears it out. Infectobesity is not limited to Ad-36. “There have been nine other pathogens reported to induce obesity in animals,” says physician Magdalena Pasarica, a researcher at Pennington’s endocrinology lab. “I’m sure others will turn up. Viruses alter things at the molecular level.” Of course, questions remain — chief among them why some people with the virus never become obese. And even if proof is forthcoming, no one is arguing that microbes are to blame for every case of obesity. “This virus may affect less than 11 percent of obese people,” Pasarica says.

NEXT STEPS

Atkinson offers mail-order testing for Ad-36 antibodies, which indicate the presence of the virus, through his company, Obetech. The $450 fee won’t buy a cure, but it does provide comforting proof that there’s more at play than just a big appetite. “Once we prove causality in humans, the next step will be a vaccine and an antiviral medication to treat obesity of viral origins,” Pasarica says. But understanding how viruses trigger fat transformation has implications beyond vaccines. According to Dhurandhar, pinpointing the viral mechanism for regulatory control over fat cells could help treat metabolic diseases in which the body does not make fat cells on its own. More relevant to obesity, once science can find the precise molecular pathways that make a person lose weight, it can start developing therapeutic targets for them. In other words, if we can reverse the process the virus uses to make fat, it may one day be possible to create drugs that eliminate the need for diet and exercise.

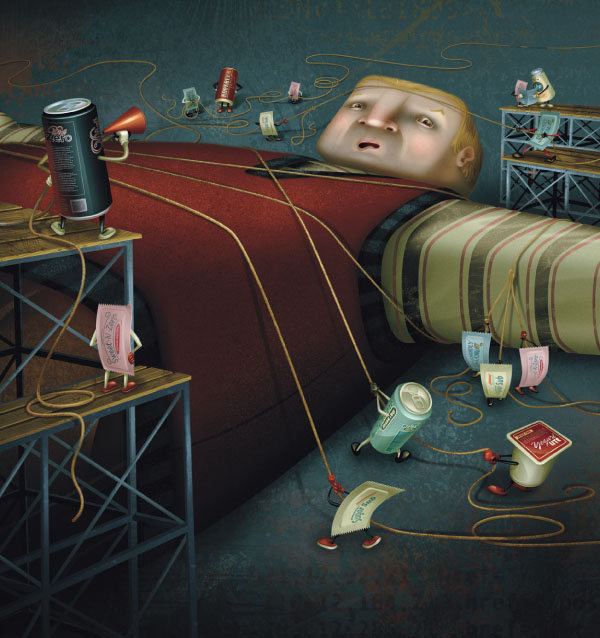

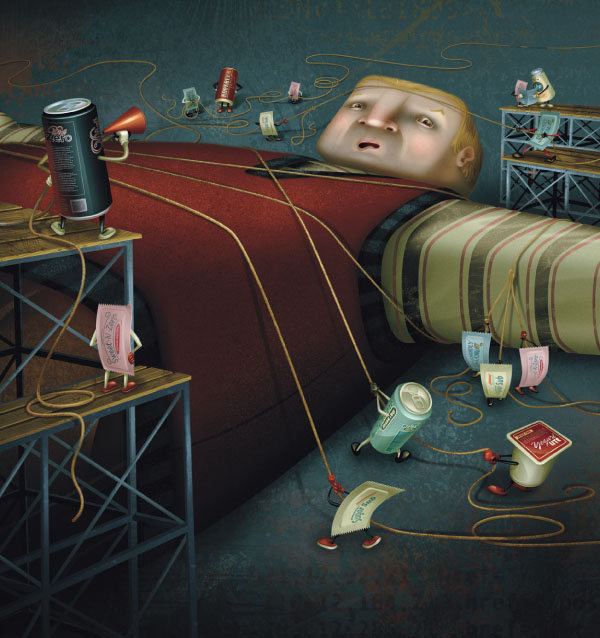

We’re Losing Sleep and Gaining Weight

THEORY

A lack of pillow time could be causing us to pile on the pounds. Sleep deprivation interferes with appetite-regulating hormones and drives us to eat more.

EVIDENCE

We’re definitely sleeping less. According to the National Sleep Foundation, Americans spend an average of six hours and 40 minutes snoozing per weeknight, compared with 10 hours before Edison invented the lightbulb. Findings released last May by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention illustrate the importance of bedtime: Of 87,000 American adults surveyed between 2004 and 2006, about 33 percent who slept fewer than six hours a night were obese, compared with only 22 percent of those who got the recommended six to nine hours. Previous studies have shown that chronic sleep deprivation increases levels of ghrelin, an appetite-stimulating hormone, and decreases leptin, a hormone that helps you register fullness. And researchers at the University of Chicago who deprived healthy young adults of sleep found that in addition to increased overall appetite, the volunteers experienced a particular surge in cravings for sweet and salty foods.

FRINGE FACTOR

This hypothesis is plausible and actionable. Sleep researcher James Gangwisch of Columbia University Medical Center believes the existing data is sufficient to recommend getting more shut-eye as a preventive measure. “This is important to the study of obesity because it’s a totally unique risk factor,” he says, “and, for the most part, it’s easily modifiable.”

NEXT STEPS

Follow-up studies now under way at the NIH and other institutions should better define the effect of sleep quality versus quantity on weight gain and offer more insights into appetite controls. In the meantime, consider this a science-sanctioned excuse to sleep in.

Pollution Is Going Straight To Our Hips

THEORY

Certain man-made chemicals commonly found in plastic — which is commonly found in everything (baby bottles, food packaging, plumbing) — cause physiological changes that can predispose us to be obese for life.

EVIDENCE

Three studies presented last May at the European Congress on Obesity shone an international spotlight on “environmental obesogens,” a term coined by Bruce Blumberg, a biologist at the University of California at Irvine and author of one of the studies. Although Blumberg and others have linked several chemicals to obesity in rodents, it’s bisphenol A, or BPA, that tends to cause the most concern. The man-made molecule is virtually ubiquitous in consumer goods, turning up in everything from plastic wrap and water bottles to toys and toothbrushes. Evidence suggests that it can mimic the hormone estrogen and interfere with the body’s natural mechanism for regulating fat cells. “We make seven billion pounds of it each year,” says Frederick vom Saal, a biologist at the University of Missouri who has been studying so-called endocrine disruptors for nearly 20 years. “There is virtually nobody in the U.S. without biologically active levels of BPA in their body.”

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey shows a dramatic nationwide increase in obesity during the same 30 or so years that production of BPA ramped up. While it doesn’t prove cause and effect, vom Saal says, “it is startling data.” Even more startling is the possibility that the fattening effects of BPA may be passed down to future generations. “Our research has shown that if you give mice a single exposure while pregnant, those offspring will be predisposed to being between 10 and 15 percent fatter as adults, for life, even if they are never exposed to it again,” Blumberg says. “That’s pretty insidious.”

FRINGE FACTOR

Frighteningly plausible. The evidence on obesogens has been well received among the scientific community and was the subject of a panel at this year’s meeting of the Obesity Society. And the government-backed National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health, supports the idea that obesity has an environmental component.

NEXT STEPS

In the short term, we can work to regulate chemical obesogens. Japan and Canada are phasing out BPA, and now several states in the U.S. are considering following suit. Without labeling laws, the best consumers can do is to avoid polycarbonate-containing plastics, those stamped with the recycling number 3 or 7. But obesogens will still exist in the environment. The larger benefit of studying them, Blumberg says, may be an increased focus on ways to prevent, rather than treat, obesity. “If, as we believe, chemicals to which we are exposed are altering our metabolism to promote the development of fat cells, this should also remove some of the onus that physicians put on patients,” he says. “It is not simply always the case that people are obese because they eat too much and exercise too little.”

Other Surprising Culprits

These four hypotheses may not lead to big, fat breakthroughs in obesity research, but they score high points for creativity.

Microwave ovens: Jane Wardle, a professor of clinical psychology at University College London, floated this theory at the 2007 British Cheltenham Science Festival after discovering an overlap between rising obesity rates in the U.K. and the microwave’s ascension to common household appliance in the mid-1980s. TV dinners and faster, easier access to food were cited as contributing factors.

Ear infections: Several studies presented last year at the American Psychological Association conference hinted at a link between childhood ear infections and obesity later in life. One study revealed that individuals with a moderate to severe history of otitis media (middle-ear infection) were 62 percent more likely to be obese; possibly, researchers speculate, because the infections damaged nerves involved in taste, affecting later food choices.

Air-conditioning: This theory holds that being exposed to less variation in extreme temperatures, thanks to the modern conveniences of heating and AC, means our bodies don’t have to work as hard or burn as many calories to maintain a comfortable 98.6˚F. Hard data is lacking, but the idea has long been accepted as fact in the field of animal husbandry, where temperature is manipulated to encourage growth in pigs.

Relationships: Your social circle can influence how round you get, according to a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Analyzing data from more than 12,000 people over 32 years, researchers found a strong correlation between weight gain and relationships. Married people were 37 percent more likely to become obese within two to four years of their spouses doing so than people whose spouses stayed trim.