We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

It’s not that hard to startle a person. Just take a disturbing-looking object and set it out of view until exactly the right moment. Then, let it fly with some bangs, pops, or screams. The light and noise hit our brains before we can process any classic phobias: spiders, flesh wounds, sharks, clowns, and so on. It’s a surprising, evocative, and simple way to make someone jump.

Which, of course, is why it’s called a jump scare. For decades, designers, directors, and writers have worked this psych-out into video games, movies, and even ads. They might throw a few special effects, but they’re usually using the same old formula. The audience knows it too—and eats it right up.

Even scientists who research horror aren’t immune to the basic terrors of sudden movements and noise. “There’s this fire truck. Lights turn on; its horn sounds; and it comes racing toward you,” says Coltan Scrivner, a human-development researcher at the University of Chicago, describing a feature of the haunted house he visited last weekend in Detroit. “It gets me every time.” Mathias Clasen, director of the Recreational Fear Lab at Aarhus University in Denmark, similarly writes that his favorite jump scare happened at a Danish haunted house called Dystopia. “There’s inevitably a room in which [the] mascot, Mr. Piggy, is hiding in the dark, awaiting the arrival of guests,” he says over email. “When he jumps out with the chainsaw roaring, my heart just about explodes.” With the appropriate triggers, it’s hard to avoid an extreme reaction.

A total body effect

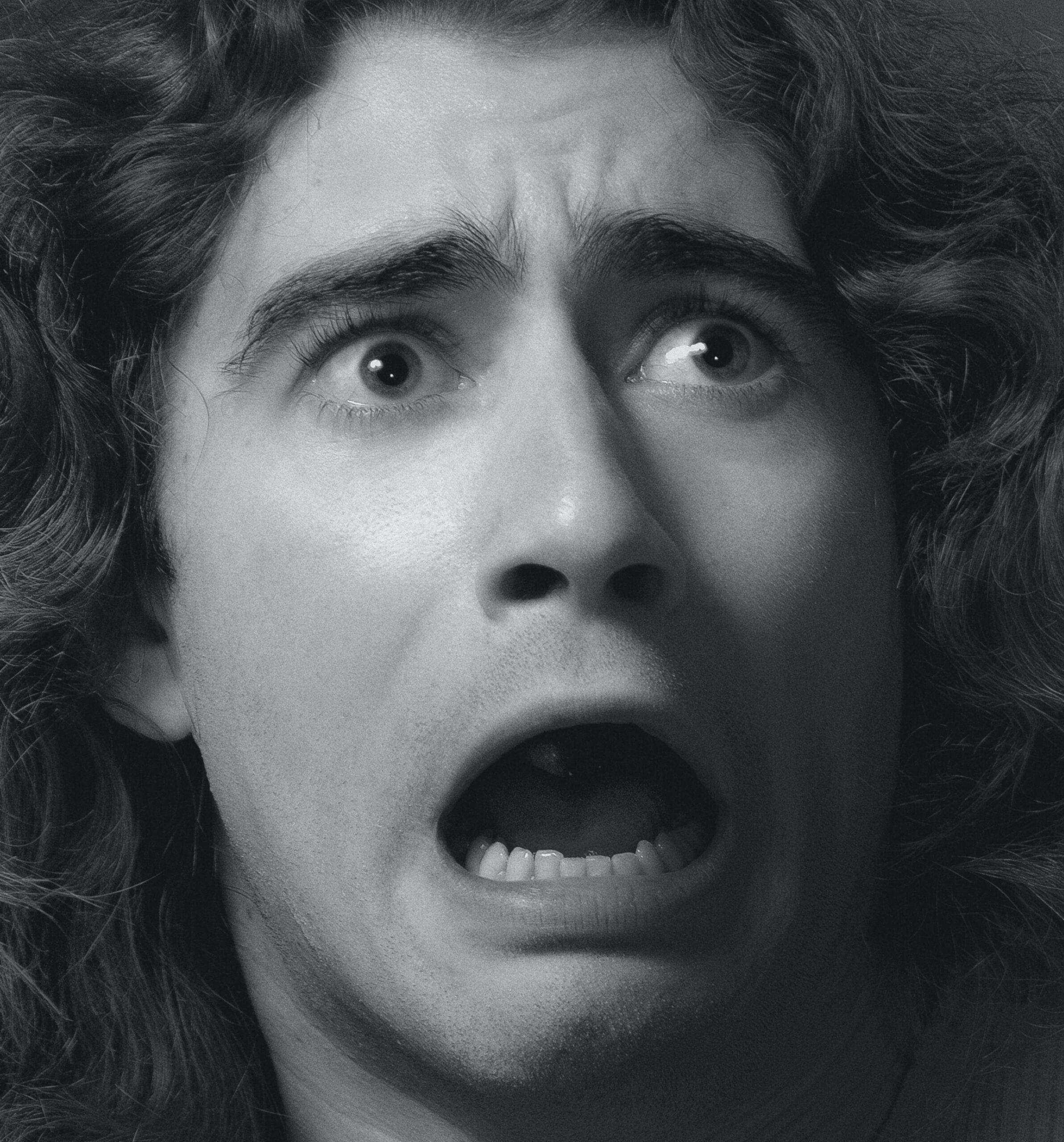

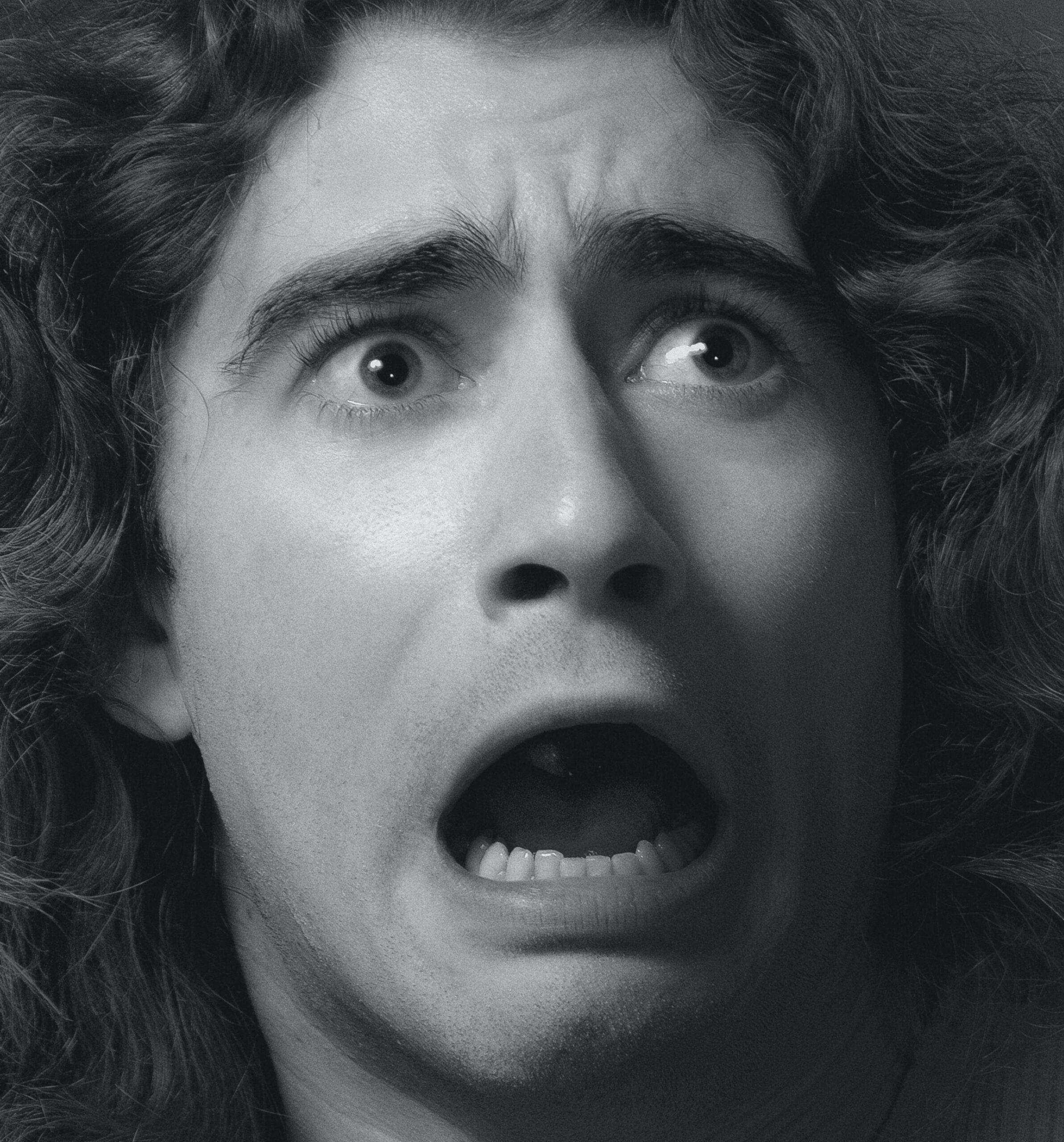

Whether we’re scared at a haunted house, in a dark street, or on the couch watching Jaws, our minds respond in a similar way. The amygdala, a key part of the brain that processes fear, lights up, says David Zald, a psychologist at Vanderbilt University and director of the Affective Neuroscience Laboratory. That same region controls startle responses in your body: jumping, ducking, or making a scared or surprised expression. Once the amygdala is activated, it cues the hypothalamus, the hormone-controlling section of the brain, to release adrenaline and prepare our muscles for action.

[Related: Why do we see ghosts?]

But there’s more to the process. The brainstem, which dates back millions of years before humans, might play the most important role in a jump scare. The locus coeruleus, an area of the brainstem, synthesizes the stress hormone norepinephrine. That, in turn, heightens our attention. “Those all are very deep-rooted circuits that are essentially an emergency response,” Zald says.

Most children learn about the “fight or flight response” in school, and our understanding of physiology reinforces it. When a person is startled, their heart rate and pressure skyrocket, blood rushes to their extremities, and their pupils enlarge to bring in as much light as possible. Their bladder or colon might even void, which is less of an obvious advantage in a dangerous scenario and more of a glitch as the brainstem overrules other orders from the central nervous system. This mindset is not ideal for making complicated decisions, or doing anything except hyperfocusing on the threat.

Cooking up spooks

Haunted house creators take advantage of the brain’s impulses by layering on other jarring effects. Leonard Pickel, the owner and chief designer of the themed-attraction consulting company Hauntrepreneurs, says that one of his favorite tricks is the drop panel. The actor inside some kind of hidden box clicks a latch, and the door falls in front of him. “It makes a giant noise, and that’s really the scare,” he says.

Experts agree that jarring, sensory experiences are universally terrifying. But there are also more subtle techniques to prime people for a jump scare. For instance, individuals who look at pictures of fanged animals or mutilated bodies react more strongly when they’re startled. Visual appetizers and scene setting can go a long way in building fear.

A recognizable soundtrack can add to the hype too. In the spirit of research, I watched Jaws as I wrote this piece. Without the tense, two-note music (nah-nah, nah-nah, nanananananana … ), it would have been a much less thrilling movie. “Sound is absolutely crucial to the jump scare,” Clasen says. Claire Gresham, co-artistic director of Ten Bones Theatre Company and voice actor, says that both a creepy, prolonged noise and a sudden roar can be scary in an audio context. “I’m thinking of The Grudge, with the prolonged creaky death rattle sound created with just breath. Or the horrifying Donald Sutherland scream-in-point from Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” she writes via email.

Sneaky tactile tactics also make people more susceptible to jump scares. But the key, Pickel says, is to make individuals nervous without terrifying them. To achieve the effect, he makes some floors of his haunted houses sink and move back and forth a little.

Life lessons

Thousands of years ago, our ancestors treaded carefully to avoid scary encounters. Today, we shell out money at theaters and theme parks to get the same fearful rush.

This is despite the stress it puts on one of our most important organs: our hearts. Last year, Scrivener and his colleagues took the heart rates of 110 people walking through a haunted house in Denmark. He said that some people’s rates hit 140 beats per minute (bpm) or above for the majority of the 45-minute tour. “That probably feels like you’re going to die,” says Scrivner, “because that’s a very strenuous workout.” To compare, the average resting heart rate for an adult is 60 to 100 bpm; after my jog yesterday, my fitness monitor read 148 bpm. Even so, Scrivener says that most of the people in his study reported that they enjoyed the haunted house.

In his greater body of work, Scrivener has sorted the people who come out of haunted houses into two basic categories: thrill seekers and white-knucklers. The thrill seekers are the kind of people who jump out of airplanes—they’re deliberately chasing down adrenaline-inducing scenarios. The white-knucklers are more complicated. They’re genuinely scared during the haunted house; their heart rates climb and stay elevated and show every other sign of being stressed. But when they finish and go over to talk to Scrivner, they say that they learned something about themselves. There are few chances in the modern world, outside of war zones, to learn how to react in unexpected, overwhelming circumstances. So in a way, haunted houses give people a chance to test their mettle—and come away with an important lesson. “Feeling very, very bad does not always translate into something very, very bad happening,” Scrivener says.

Another pattern Scrivener has seen is that people with clinical anxiety are more likely to gravitate to horror movies and other frightening media. But there’s a key element with those thrills that’s often not available in real life: control. A horror movie or book is a source of anxiety that we can be in charge of, as opposed to a more insidious mental condition. We know what the source is, how long it’s going to go on for, and where the exits are.

All in good fun

Scrivener hasn’t found any long-lasting negative effects of recreational scares. Clasen agrees: “I have seen no compelling evidence to suggest any kind of real danger.”

[Related: This sound illusion puts the scary in scary movies]

In fact, there’s a sweet spot in the axis of fear where people enjoy themselves, and they tend to self-sort, Scrivener says. For example, I enjoy 20th-century mystery novels with murders that happen far off scene. And while I considered going to a haunted house to report this story, all the available options looked too scary for me—so I ended up watching Jaws on my couch under a gravity blanket, and hid my eyes every time the nah-nahs intensified.

Other people might also prefer to watch horror movies at home, rather than a theater where they’re blasted with screams and tense music. And for those who wants to prepare for the jump scares, research the tropes and when to expect them. First, someone’s probably going to be hiding behind the fridge door. Second, bad things always happen in the bathtub.

In real life, however, scares are less predictable. Scrivener has found that people develop mental strategies to make themselves more or less scared, depending on how much stimulation they’re aiming for. White-knucklers might crack a joke after a serious fright or look up haunted house spoilers ahead of time, whereas thrill seekers will immerse themselves in the experience and enjoy it for what it is.