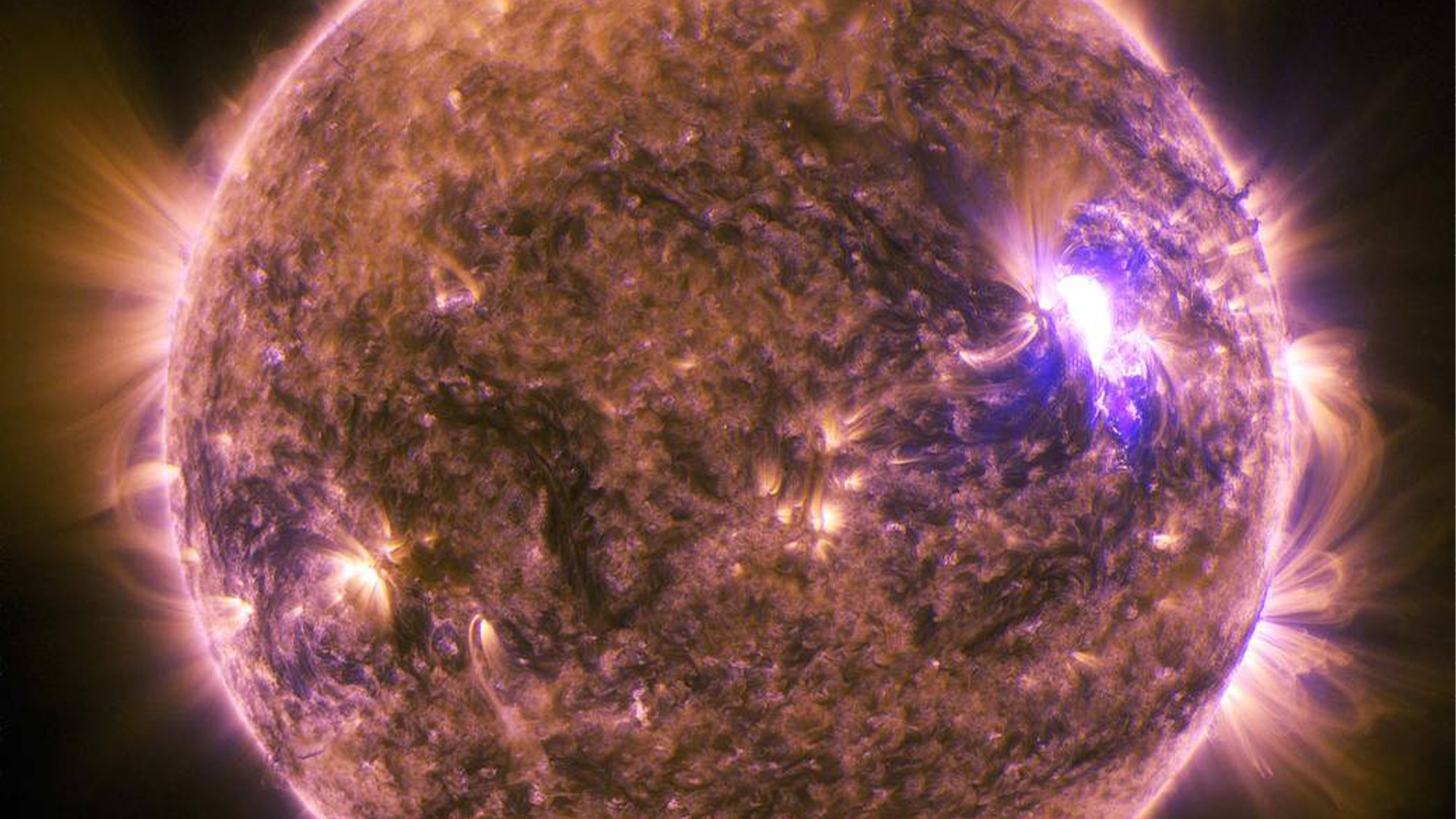

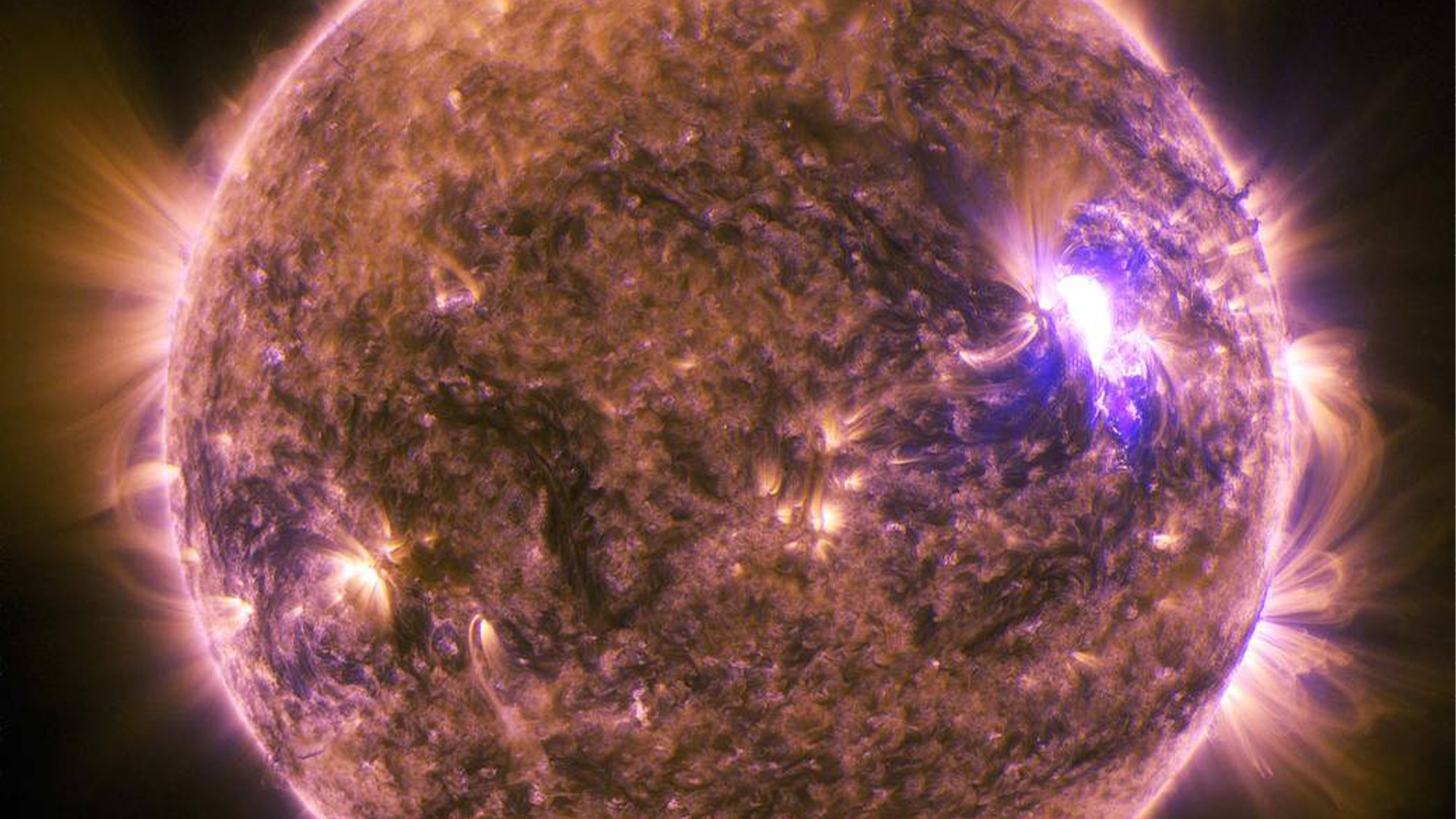

Space weather can be wild. Coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which can produce solar flares, are especially blustery, and can cause everything from beautiful auroras that dance across the night sky or power outages and other technological interference. They can even endanger astronauts by throwing radiation their way.

But like with weather on Earth, can we improve predicting when bursts of electromagnetic energy like solar flares are coming?

[Related: How worried should we be about solar flares and space weather?]

A team of scientists from NorthWest Research Associates (NWRA) investigated data from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) and found some new clues for weather prediction in the sun’s upper atmosphere. The identified small signals in the sun’s corona that can help pinpoint when regions in the sun are more likely to produce the bursts of light and particles released from the sun during a solar flare.

They detail the findings in a study published January 16 in The Astrophysical Journal. Most importantly, they discovered that in the regions about to flare, the corona produces flashes “like small sparklers before the big fireworks.”

Previously, scientists have studied activity in the lower layers of the sun’s atmosphere (specifically the protosphere and chromosphere) and how it can signal impending flare activity in active regions. This warning is typically marked by groups of strong magnetic regions of the sun that appear darker and cooler than the surrounding area called sunspots.

“We can get some very different information in the corona than we get from the photosphere, or ‘surface’ of the sun,” said KD Leka, lead author on the new study from Nagoya University in Japan, in a statement. “Our results may give us a new marker to distinguish which active regions are likely to flare soon and which will stay quiet over an upcoming period of time.”

[Related: World’s largest telescope array is almost ready to stare straight into the sun.]

The team used a new publicly available image database of the active regions on the sun captured by the SDO. It combines more than eight years of images of images taken using ultraviolet and extreme-ultraviolet light. The images and a newly developed statistical method created by co-author Graham Barnes will help scientists better understand the physics happening in the sun’s magnetically active regions.

“It’s the first time a database like this is readily available for the scientific community, and it will be very useful for studying many topics, not just flare-ready active regions,” said Karin Dissauer, a co-author and NWRA research scientist who led the database project along with engineer and co-author Eric L. Wagner, in a statement. “With this research, we are really starting to dig deeper. Down the road, combining all this information from the surface up through the corona should allow forecasters to make better predictions about when and where solar flares will happen.”