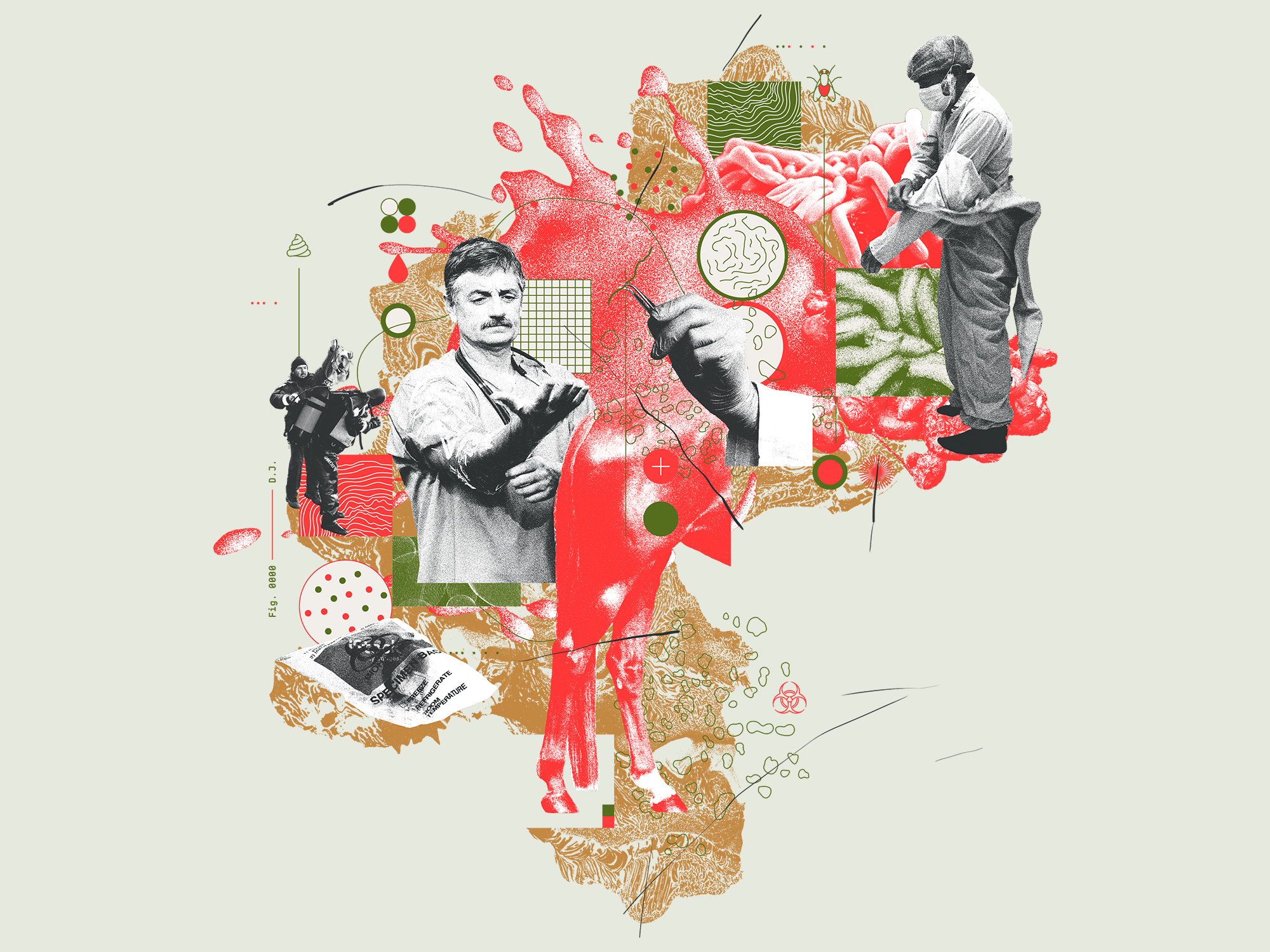

THERE’S SOMETHING DEEPLY respectable about messy work. Someone who slams their coffee and starts their day with decomposition lives a hero’s journey. One second our intrepid adventurer is eating a granola bar in the car, and the next they are face-to-face with something so gnarly that they can’t talk about work over dinner. But without them, the world would be a more dangerous—and more disgusting—place for the rest of us. Diving through feces to retrieve corpses, scooping armfuls of fish slime, and cooking human organs into sanitized mush subjects stomachs, noses, and souls to a full-on sensory onslaught. To those who take on some of the filthiest jobs in science: We salute you.

MOSQUITO FEEDER

When it comes to killing people, nothing outdoes the mosquito. In 2020 these disease-wielding insects took out an estimated 627,000 of us with malaria alone, outpacing the rate at which humans kill each other. Entomologists hope to lower that body count by curbing the bugs’ ability to transmit deadly pathogens, but that scholarship requires blood to keep a brood alive.

While some labs wean the insects onto convenient diets like rodents, they’re always keener to feed on their natural supply—human hemoglobin, straight from the source. That’s why some experts eager to mimic real-world conditions offer up their own limbs. They willingly submit their arms to a cloud of hungry bloodsuckers, who sup upon the iron-rich essence of life. During feeding, raised welts can become so numerous that they fuse into one swollen expanse of histamine reaction. Fierce itch aside, at least it’s not a huge loss: Feeding a crew of 5,000 skeeters requires about half an ounce of blood (you give the Red Cross 32 times as much in one go).

VOLCANOLOGIST

Beneath our feet lurks a terrible ocean of liquid rock that occasionally spurts to the surface in a destructive splatter. Volcanologists tell us why, how, and when this molten earth vomit will emerge so we don’t get caught unawares. Even for those who choose this path, it stinks. Volcanic gas is full of hydrogen sulfide, which smells like rotten eggs. The foul compound can reach dangerous levels on these moving mountainsides, requiring researchers to mask up in the grime. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration sets the permissible exposure limit for H2S at 20 parts per million, which is up to 2,000 times our nose’s olfactory threshold for picking up the stanky substance.

Studying volcanoes means asking questions like How much ash raining down on me is too much? and Is the amount of pumice falling out of the sky going to be a problem this afternoon? Observing an eruption means a work environment filled with liquid rock up to 2200°F, which pits scientists against obstacles like sweat-dampened clothes and continuously grimy equipment.

ARTIFICIAL INSEMINATION TECHNICIAN

Fields from biotech research to conservation rely on our ability to breed animals more or less on demand. This requires techs who know how and when to squirt semen into a uterus to best make a baby—and an understanding of anatomy, physiology, and animal behavior. Also: a willingness to come face-to-face with a fair bit of poop.

Before inseminating a horse, for instance, one must stick one’s arm up the rectum and use fingers and an ultrasound probe to check the ripeness of the ovarian follicles. If they’re ready, a clean hand goes inside the mare’s vagina with a semen-filled pipette to reach the cervix, which feels like a small, puckered mouth. For larger animals, like elephants, even going armpit-deep won’t get you where you need to go: The semen—collected with the help of manual rectal stimulation—is delivered via a long, flexible endoscope. High-level inseminators get certified by programs that meet the standards of the National Association of Animal Breeders, which can help them stand out in the job market. Anything to get a leg up against the competition is helpful, given that most folks in the industry freelance.

COMMENT MODERATOR

Assessing the legality and safety of notions people post online might not be viscerally smelly, but moral disgust can have physical side effects. Think of revulsion as a kind of behavioral immune system. Some evolutionary psychologists suggest our tendency to get emotionally squicked out is tied to the same instinct that keeps us from eating things that could make us sick—yes, retching over immorality may have the same root as puking over piles of maggots. Avoiding fraught situations may not keep you from getting food poisoning, but it’s still self-protective in the social sense.

Like the job itself, research on the effects of moderation is in its infancy. But with an estimated 100,000 people working in the field—and some evidence that they can develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder—psychologists say we must grapple with the enormous mental toll of sifting through the worst of the internet.

MAGGOT FARMER

Large-scale maggot farming focuses on the alchemy of turning trash into sustenance. The protein-rich fly babies are perfect for feeding farmed chicken and fish—and with global food scarcity looming, that market may be broadening to include the rest of us. But how do we turn the writhing hordes that swallow roadkill into nutritious grub?

It starts simply: by letting flies squirt their eggs in the vicinity of organic waste—poop, offal, rot—and allowing their darling offspring to hatch and eat to their hearts’ content. Harvesting the maggots, well, that’s a little more complicated. Some farmers create escape tubes for the larvae to crawl into on their own. Others harness the power of the sun, smearing infested manure over a sieve so the squirmers dig away from the light and fall into a tub. And then there’s the water method, in which harvesters flood the fetid feeding grounds with water, sending a mass of maggots floating, to be scooped up and gathered from some kind of unholy approximation of a cranberry bog and mashed into a protein-rich slurry. Bottoms up!

BODY FARM FORENSIC ANTHROPOLOGIST

Every year roughly 4,400 unidentified corpses turn up in the US alone. To figure out who they were and how they died, one must factor in how different circumstances can affect decomposition. Traditionally, court cases used data from pigs and rabbits to determine time of death, but humans break down differently. We know that thanks to the University of Tennessee, Knoxville’s Forensic Anthropology Center, which was the first facility of its kind when it opened in 1987.

Donated corpses lie around the joint—known as the Body Farm—in a variety of experimental conditions. They might nestle under a few inches of topsoil, hide haphazardly in the underbrush, or get pinned underwater. All so grad students, faculty, and visiting researchers can watch (and smell) them rot. Putrescine, which evokes old fish, and cadaverine, which smacks of ripe roadkill, are two notoriously funky compounds produced when amino acids break down. But this isn’t just an olfactory assault: Work at the Body Farm requires keeping all the senses on high alert. One might observe and photograph munching beetles, for instance, to collect info on how their appetites can shape a crime scene.

MATERIALS SCIENTIST, HAGFISH SLIME

Hagfish slime is a remarkable substance. When threatened, the phallic-looking fish secrete goo from lines of glands that line their flanks. When the ooze hits the water, it expands by a factor of 10,000 in less than a second. In addition to creating an extremely icky barricade to ward off predators, the muck can gum up gills and choke even fearsome sharks. Composed of mucus and a network of silklike protein threads, the gunk may one day play an important role in manufacturing materials for ballistics shields and firefighting. But for researchers to study it, they have to harvest it.

Zoologists trigger this slimy reaction by pinching hagfish on the tail with forceps. Like dropping a value-size tub of hair gel on the floor, handling these critters involves a high degree of slip. Case in point: In 2017, a truck carrying 7,500 pounds of hagfish destined for South Korean dinner plates overturned, sliming an entire Oregon highway and covering a whole Nissan sedan.

HAZMAT DIVER

Humanity tucks a lot of its dirty secrets in the drink. Hazmat divers have the technical skills—like accreditation in underwater welding—to clean up when those pent-up truths cause gruesome accidents. Think fixing ruptured nuclear reactors and scouring the insides of septic tanks. To do such risky work under such disgusting conditions, divers wear sealed helmets and suits of thick vulcanized rubber, lest the fetid fluids they swim through get inside their gear and into their vulnerable orifices. Once the swimmers surface, they require thorough decontamination. They’re so noxious, even the folks hosing and scrubbing them down have to wear protective gear.

The psychological burden of kicking through feces is significant. But on the bright side, the skills required mean that if bobbing in crude oil for dead bodies becomes too much, these professionals are well equipped to take on repairs in clean and safe waters too.

OIL SPILL CLEANER

Cleaning the liquid remains of ancient flora and fauna off of flailing and dying marine life is dirty work—especially since the mess gets worse over time. Fouling, or oiling, as it’s called, leaves birds unable to fly. The goop covers everything in its path too quickly for rescuers to save every organism, so slicked beaches sometimes fill up with dead fish. In life, the swimmers are packed with trimethylamine N-oxide, a compound that protects them from the high pressure of the ocean. In death, that turns into trimethylamine, more commonly known as the dreaded rotten fish smell. There’s nothing like the pungent vapors of climate doom mixed with notes of gas station sushi in the morning.

Manually scrubbing up an oil spill means using gloves and shovels and rakes and industrial vacuums, skimming through the water to catch the hydrophobic mess floating on top, and then setting the sea on fire to burn away what’s left. Toxicity from exposure to the myriad noxious compounds involved can lead to skin, eye, neurological, and breathing problems.

MEDICAL WASTE COOKER

Hospitals, pathology labs, and other places where the insides of bodies make their way outside all generate biohazardous waste. That refuse can’t go into the trash raw because it can carry pathogens, radioactivity, or chemotherapy residue. Even something routine like a busted appendix can’t just slip into a flip-top garbage can. There are several ways to make such tissues more benign, including popping viscera into high-temp autoclaves that subject them to steam sterilization. That’s right: They get cooked.

The unceasing demand for waste disposal makes this a steady job regardless of market fluctuations, and some employers (be they hospitals or specialized outside vendors) provide on-the-job training. The downside is that braising a body part creates all sorts of…aromas. When a technician throws a bag of tumor or placenta or pus-soaked hospital linen into what is essentially a weapons-grade Instant Pot, it can create a veritable smorgasbord of odors—a fetid amalgam of puke and iron and hot flesh that smells a little too much like barbecue. There are a few ways to help mitigate the stink, such as using mechanical scrubbers that wash the air, adsorptive filters that catch the funk, or even little dots of topical camphor rub above the top lip, but let’s be real: This gig is not for the faint of nose.

This story originally ran in the Spring 2022 Messy issue of PopSci. Read more PopSci+ stories.