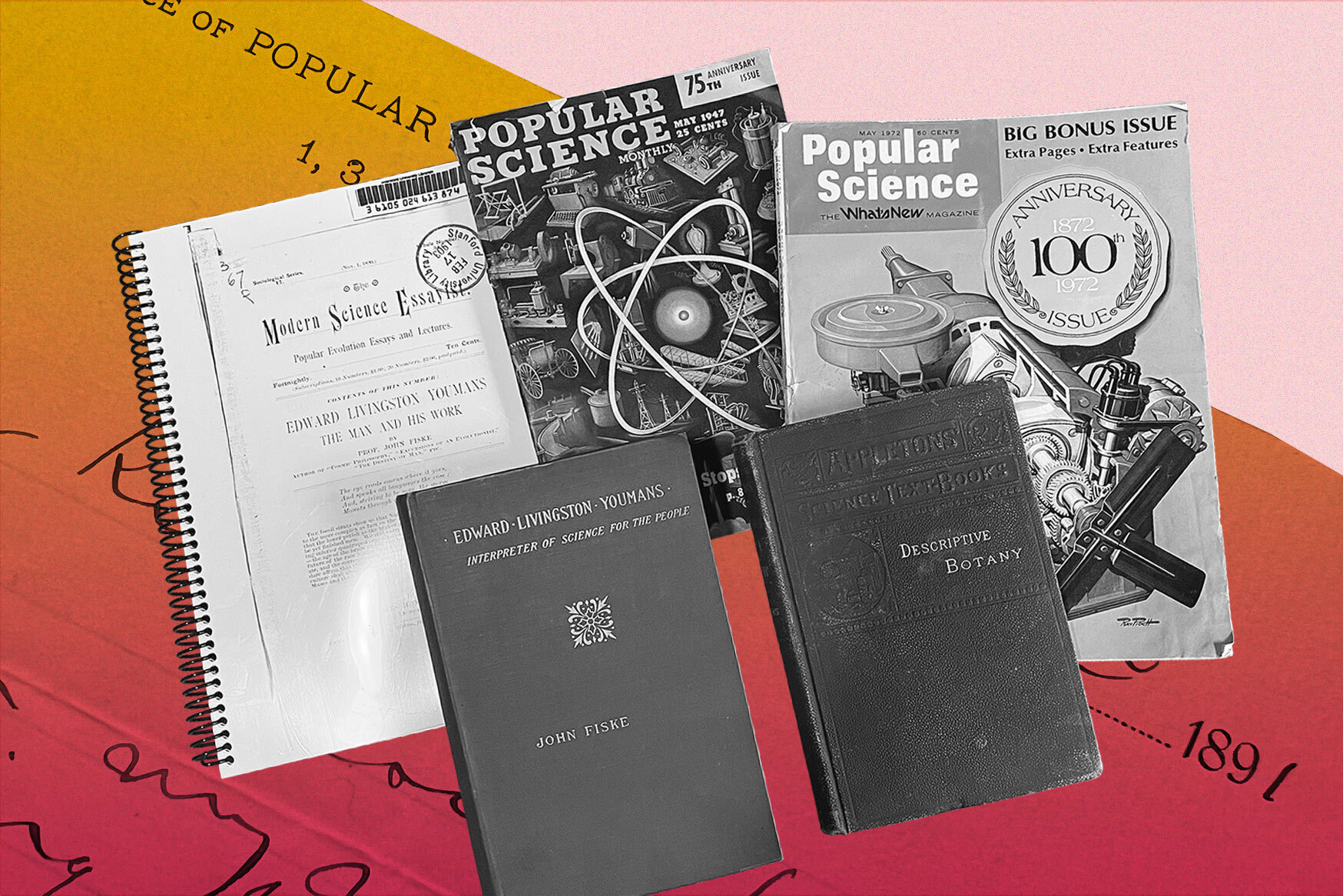

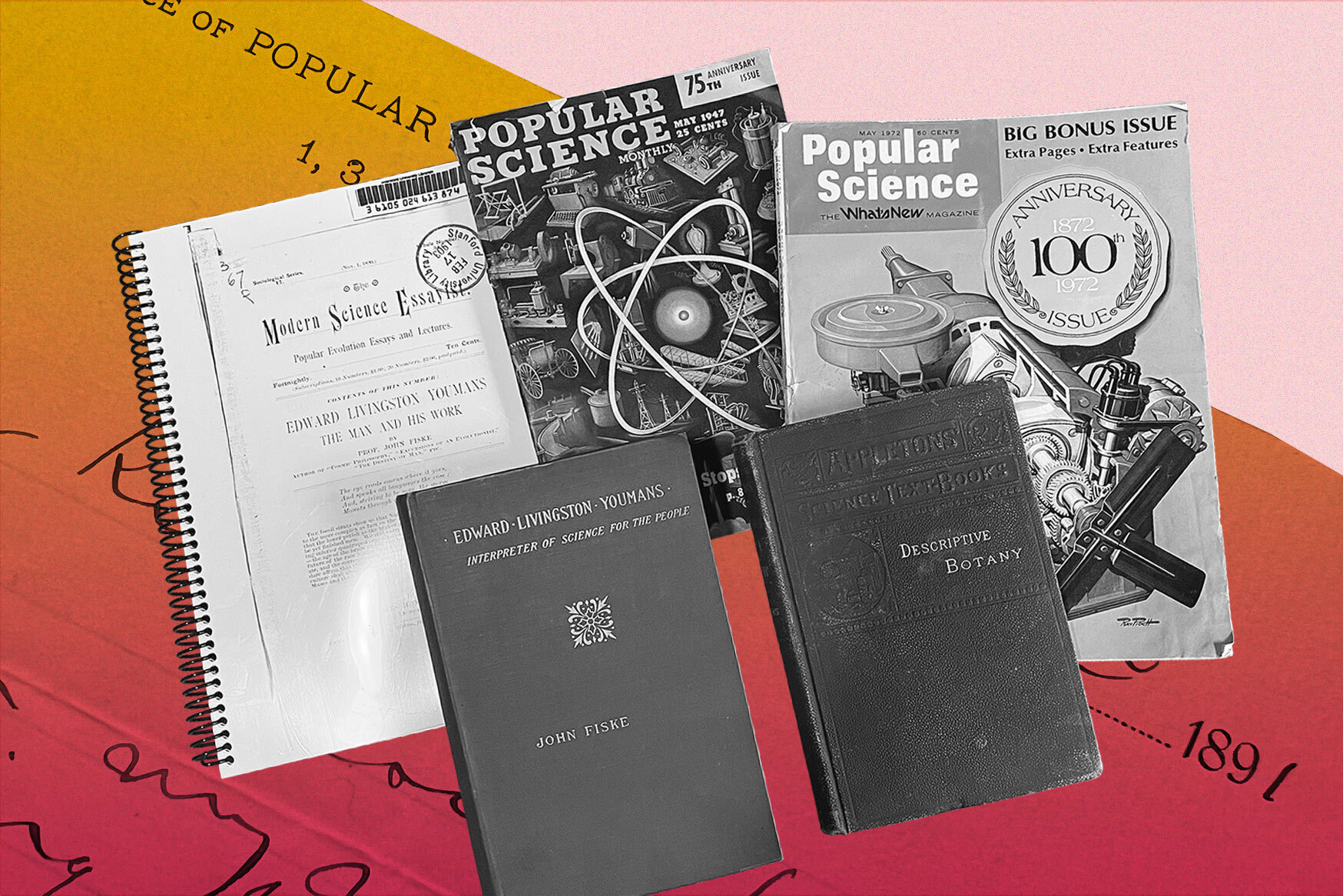

“The work of creating science has been organized for centuries,” wrote Popular Science founder Edward Livingston Youmans in his inaugural editor’s note in May 1872. “The work of diffusing science is, however, as yet, but very imperfectly organized, although it is clearly the next great task of civilization.”

Over the last 150 years, the editors of Popular Science have published 1,747 issues, countless web articles, hundreds of videos, and more in our continuing effort to answer that charge: To as perfectly as we can organize the world of scientific inquiry and innovation for curious everyday people as best we can. Or, as Youmans put it, for whoever cares “how opinion is changing, what old ideas are perishing, and what new ones are rising into acceptance.”

Youmans believed that the US was home to “many such” curious minds, and that they would “only become more numerous in the future.” Within just a few years, he was proven correct. Circulation of the periodical grew to 11,000 by the end of 1873 and had reached 18,000 by the time Youmans died, in 1887, at the age of 65. (His brother and collaborator, William Jay Youmans, took up editorship through 1900.) Today, Popular Science reaches an audience of millions across our varied platforms.

At Youmans’ behest, the publication came into existence at a pivotal moment in the history of science and invention. Then called The Popular Science Monthly, the magazine entered a world where a growing repository of scientific knowledge—one that included vaccines, telegraphs, electricity, locomotives, typewriters, industrial machines like lathes and drill presses, and new materials like vulcanized rubber—was poised to impact everyday life. The barrier between laboratory science and applied science was vanishing. New work quickly spurred more work and fresh experimentation, a dynamism that demanded rapid interpretation.

Youmans implored his authors, most of whom were among the era’s most prominent practicing scientists and philosophers, to translate their work into language those outside their fields could more readily understand. “Eight-tenths of the patrons of the Monthly will get but a partial comprehension of it,” he wrote in a letter to an author explaining his need to edit out jargon in an article about new concepts in mathematics. (A predecessor of mine called this drive to distill complexity without sacrificing accuracy “radical clarity,” a phrase that has echoed in my brain for some 13 years.)

So it was until the early 1900s, when a change in publisher opened up an iconic period for PopSci, one with vibrant, illustrated covers and images showcasing rapid progress. Editors sought to not simply explain the present, but explore visions of the future. Our early years trotted out a series of world-changing firsts: phone calls, radios, flights, atomic bombs, automobiles, television. By the mid-century, with World Wars in the rearview, the editors began to imagine a world of buzzing metropolises, flying cars, and, of course, personal jetpacks.

If Youmans’ initial goal was to educate his audience, then here began a phase of aspiration: a shared ideal that science and technology were funnels to a better, safer, healthier, happier, more exciting existence.

In the years since, editors have dubbed PopSci “The What’s New Magazine” and adopted taglines like “The Future Now.” But the Popular Science of 2022 does not exist purely in either the educational or the aspirational realm.

Since our Last Big Anniversary Year (number 125, in 1997), we’ve experienced a paradigm shift in the role of science in everyday life. In June 2007, Steve Jobs showed the world the iPhone for the first time, setting in motion a change in the average person’s daily interface with technology and information. Our collective ability to find—and share—that information with such great ease has made parsing the clamor more difficult than it’s ever been.

We still believe in a better future—a relentless optimism that sees the potential to make good out of even our toughest challenges—but the Popular Science of the COVID-era world is first and foremost a lighthouse of the now. In many ways, we’ve gone back to the basics, which has invited a few barbs about how PopSci now cares more about being “popular” than about “science.” When you look closely, however, what we’ve actually done is fully embrace what the word “popular” really means.

To the current generation of Popular Science editors, popularity means meeting people where they are, and introducing them to scientific concepts through the lens of their own daily experiences. It means satisfying a universal sense of wonder that subtly reminds everyone that we’re all beneficiaries of science—and that most of us, whether we realize it or not, are already big fans of it too. It also means ensuring our work speaks to the population not as a homogeneous mass, but as a diverse bunch with shared needs and interests. And many different ones too.

We only wish we’d gotten here sooner.

Paging through our early days puts us face-to-face with representations we’re not proud of. World War II provides a particularly potent example, as caricatures of enraged Japanese pilots stand in stark contrast to stately depictions of American victors. (In 1945, the editors, we must note, made no celebration in their commentary following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.) After the War, our view of life at home painted what’s now a reductive, discriminatory picture, casting women as homemakers and people of color as domestic workers. A modern eye will even find sexism encoded in articulations of our mission, championing that “the man who masters a balky furnace and the woman who bakes a better muffin are often unconscious scientists” in a May 1947 75th anniversary retrospective.

Our publication has also contributed to egregious wrongs. It could be argued, for instance, that our founder was integral to the dissemination of social Darwinism in the US. British philosopher Herbert Spencer, a contemporary of Darwin who coined the phrase “survival of the fittest” in his 1864 book Principles of Biology, applied ideas about evolution and inheritance sociologically: He offered that those who thrive in society deserve their wins while those who flounder have earned their losses. Youmans’ zeal for his work led to its publication in our first issue, and nearly a dozen times after.

Spencer’s ideas—and related interpretations of Darwin’s theory of evolution—would inform a chilling era in American science.

Around the turn of the 20th century and into the early 1900s, Popular Science lent credence to the eugenics movement, a field of study that proposed a path to perfect civilization through selective breeding. Now rightly regarded as bigotry under a veneer of pseudoscience, the ideology applied advances in our understanding of evolution and genetic inheritance to support racist, sexist, and xenophobic policies that disproportionately impacted Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people. Eugenicists pushed through laws that allowed states to forcibly sterilize persons deemed “feeble-minded” and legislation that excluded certain nonwhite immigrants. Searching the first 25 years of our archive nets dozens of articles presenting supposedly scientific arguments for such practices. Historians now widely accept that American eugenics had an outsize impact on the genocidal policies of the Nazi party.

In eugenics, PopSci’s founding writ to deliver science to the public was also our Achilles’ heel. Our continued coverage of the field and its proponents only served to normalize the idea. In 1923, Senator Arthur Capper of Kansas washed the practice as “the science of fitter families” in an article recounting eugenic successes in the state. A 1925 dispatch from Chicago described with fanfare a device that could predict the inheritance of criminal behavior. As recently as 1962, a retrospective we published highlighted the movement—this time citing proof of eugenic ideas allegedly observed within a particular South African tribe—without critical comment.

Investigating ugliness in our past is a vital part of our future. In addition to deciphering the world of science for everyday readers, it has long been part of our ethos to embrace and explore faults—and to be constructive as we chart a path forward. In our last quarter century, for instance, the distasteful eugenic period has driven us to bring greater cynicism to topics from DNA sequencing to designer babies. And coverage in the magazine and on popsci.com under the current generation of editors has broadened its focus to explore how racism continues to pervade in science and society, including in drug criminalization, environmental destruction, and inequities in public health.

This month we’re continuing that work by introducing a series called In Hindsight: a collection of stories highlighting researchers from the last 150 years whose contributions are missing from our pages, but who deserve recognition. In our 75th anniversary retrospective, editors trumpeted a roster of 12 white men who “helped popularize science.” We’re only just beginning to fill in the gaps. Some of the great minds we’ll showcase, like microbiologist Esther Lederberg, made key contributions to prizewinning work, while others, like physicist Carolyn Beatrice Parker, had their brilliance cut short by barriers of sexism and racism.

These profiles also include the story of our founder’s sister Eliza Ann Youmans, a botanist and textbook author. Eliza’s contributions to her brother’s early work and PopSci are by no means a secret: His biographers regularly note that she was his reader and scribe during a period of blindness in his twenties, and she penned numerous articles and reviews for the magazine, including his obituary. But generally speaking, we know precious little about her and the extent to which her influence may have shaped and marked the brand’s earliest years.

While we know it’s important to embrace our shortcomings, there’s certainly more in our history to be proud of than not. Over the decades, we successfully delivered dispatches on science’s watershed moments and the stories of the scientists behind them. In 1883, we published the revolutionary idea that microscopic germs, not bodily impurities, caused disease. In 1931, a Popular Science reporter was there when Auguste Piccard became the first person to reach the stratosphere (we also watched when Felix Baumgartner jumped from those same heights in 2012). And, in 1984, we were among the first to get up close with Steve Jobs and his new Macintosh computer. This month, we’ll be resharing one such story every weekday, providing a tour through world-changing breakthroughs like Salk’s polio vaccine and allowing readers to peek into the past—and the marvelous visions it held of our future.

Over the coming months, we’ll also be checking in on our progress toward some of innovation’s most-compelling ideas in the Are We There Yet? series. Here, we’ll assess the realities of those visions and gut-check their feasibility, practically, and necessity. We’ve been wondering, for example, if medical science will find a cure for aging since at least 1923, asking when artificial smarts will supplant baseball umpires since 1939, envisioning cities with “complete streets” since 1925, and questing after airplanes that fit in household garages since 1926.

Of course, we’d be giving PopSci’s founding legacy short shrift if we didn’t also look at the scientific moment we’re in now—and speculate smartly on what the future might hold. Our Summer digital issue (out now) explores the current state of technology through our species’ ever-changing relationship with metal. Central to that is our current tug-of-war with the conductive elements we need to power a wave of electrification. We’re also publishing a special newsstand-only print edition that calls on 50 visionaries—from neuroscientists to sci-fi authors—to gaze into the next 150 years and tell us what they see.

Popular Science, even after 150 years, is not unlike those visions: a work in progress. It’d be an act of great hubris to claim we’ve reached the goal post our founder set of perfectly organizing the dissemination of science. To claim otherwise would be unscientific. One of Zeno’s great paradoxes, after all, holds that it’s impossible to close the gap between two things. What we can claim, however, is increasingly rapid progress toward that North Star.

Check out all our anniversary coverage here.