It’s pretty difficult to know what was on the menu for Neanderthals, particularly since smaller items like birds don’t usually leave many archaeological traces behind. While we know that some cooked crab and other seafood and that they hunted for larger game, understanding more about their diets is critical to understanding how these incredibly adaptive hominins thrived in very different environments. To do this, a team of scientists tried cooking modern birds using the methods and tools that would have been available to Neanderthals. The process is detailed in a small study published July 24 in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology.

[Related: Humans have been eating hazelnuts for at least 6,000 years.]

“Using a flint flake for butchering required significant precision and effort, which we had not fully valued before this experiment,” Mariana Nabais, a study co-author and archaeologist at Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social in Spain, said in a statement. “The flakes were sharper than we initially thought, requiring careful handling to make precise cuts without injuring our own fingers. These hands-on experiments emphasized the practical challenges involved in Neanderthal food processing and cooking, providing a tangible connection to their daily life and survival strategies.”

Neanderthal butchers

Neanderthals hunted large animals–including cave lions–but scientists know less about the smaller avian species that some Neanderthals ate. To learn more, the team tested the food preparation methods that they may have used on various wild birds. They were hoping to see what tool traces are left behind on animal bones and how those traces compare to the damage caused by more natural causes of death.

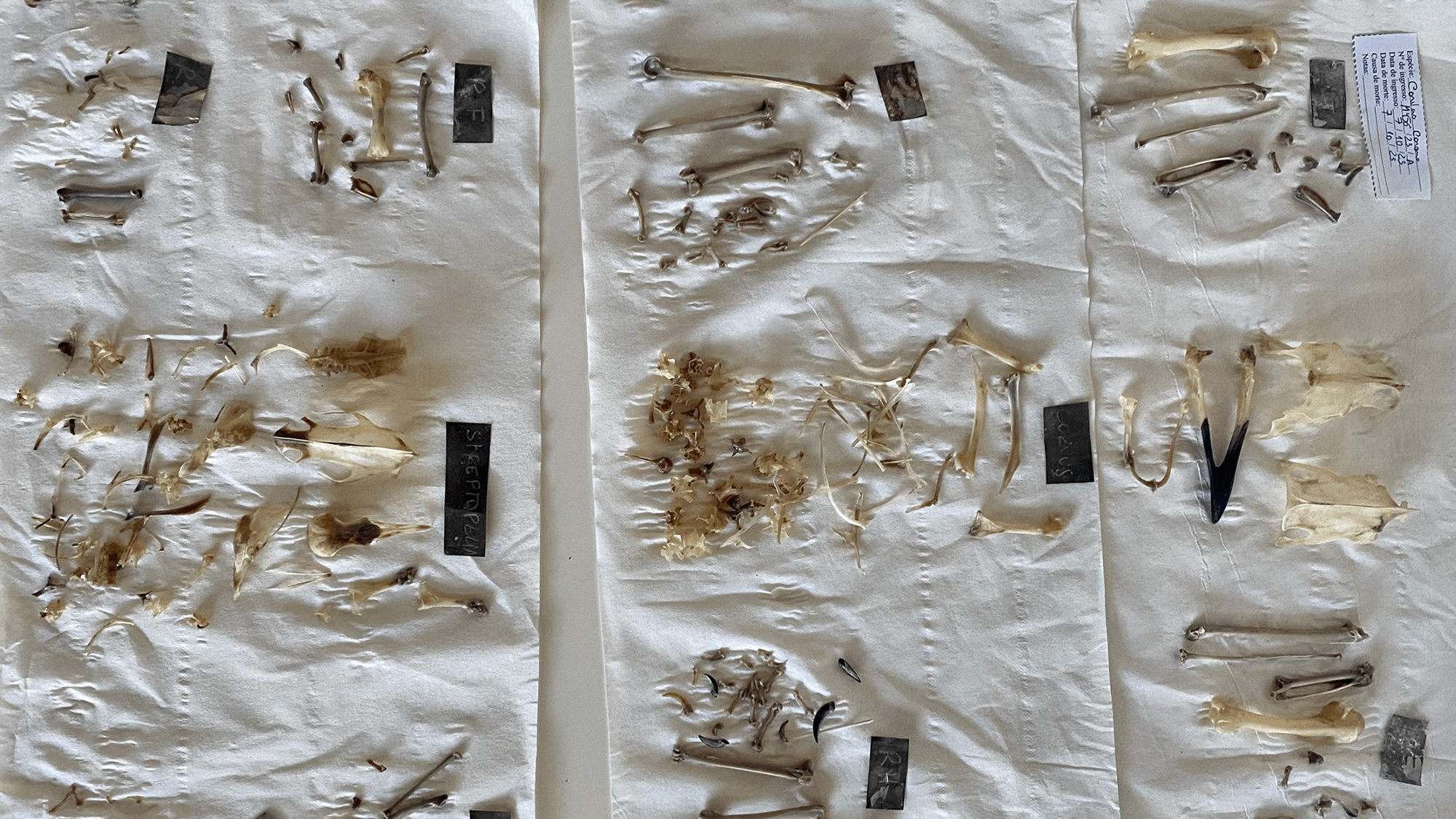

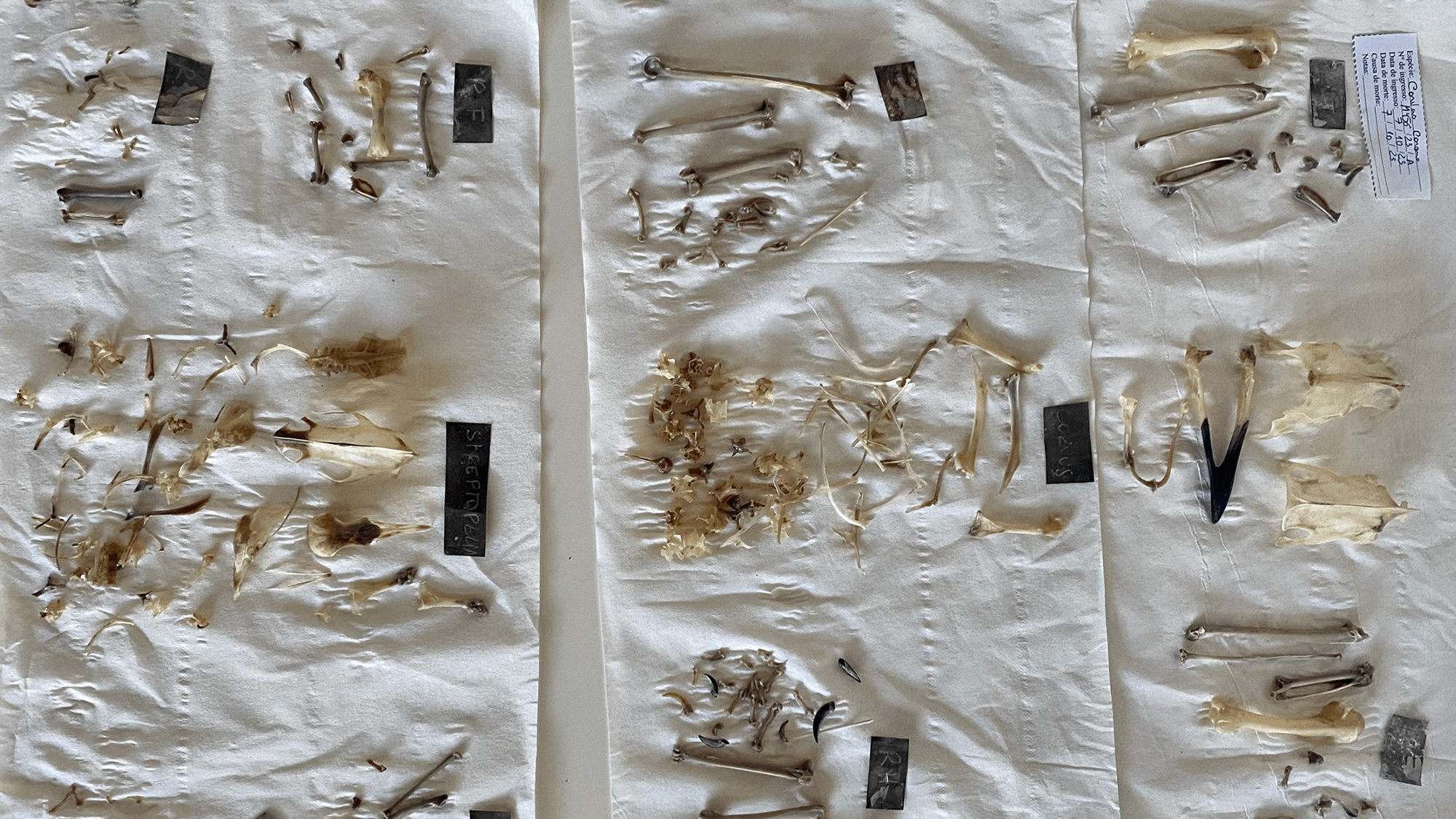

The team created an experimental database that can be compared with the findings from real archaeological sites. To build it, the team collected five wild birds that had died of natural causes from the Wildlife Ecology, Rehabilitation and Surveillance Centre in Gouveia, Portugal. The team selected two carrion crows, two collared doves, and a wood pigeon–similar species to what Neanderthals might have eaten. To select the cooking methods, they referred back to evidence found in the archeological record and ethnographic data.

Each bird was defeathered by hand. One collared dove and one carrion crow were butchered raw using a flint flake. The remaining three were roasted over hot coals until cooked, then butchered. The team found that this second method was easier than butchering the raw birds.

“Roasting the birds over the coals required maintaining a consistent temperature and carefully monitoring the cooking duration to avoid overcooking the meat,” said Nabais. “Maybe because we defeathered the birds before cooking, the roasting process was much quicker than we anticipated. In fact, we spent more time preparing the coals than on the actual cooking, which took less than ten minutes.”

Bones that are not built to last

The team then cleaned and dried the bones and examined them under a microscope for cut marks, breaks, and burns. They also looked at the flint flake they had used for evidence of wear and tear during butchering.

While they had used their hands for most of the butchery, the raw birds needed the flint flake. This left small half-moon shaped scars on the edge. The cuts used to remove the meat from the raw birds didn’t leave any taxes on the bones, but the cuts aimed at tendons left marks similar to ones on bird remains found at archaeological sites.

The roasted birds had bones that were much more brittle. Some had completely shattered and couldn’t be recovered. Nearly all of them had black or brown burns consistent with controlled exposure to heat. The black stains suggested that the contents of the inner cavity had also burned. This evidence sheds indicates parts of how Neanderthal food preparation could have worked, but also sheds light on how visible that preparation may be in the archaeological record. While roasting makes it easier to access the animal’s meat, the increased fragility of the bones means that the remains might not be found by archaeologists.

[Related: Bronze Age nomads used cauldrons for blood sausage and yak milk.]

To gain a better understanding of Neanderthal diets, future studies could include more species of prey and also processing birds for non-food products, like feathers or talons.

“The sample size is relatively small, consisting of only five bird specimens, which may not fully represent the diversity of bird species that Neanderthals might have used,” noted Nabais. “Secondly, the experimental conditions, although carefully controlled, cannot completely replicate the exact environmental and cultural contexts of Neanderthal life. Further research with larger samples, varied species, and more diverse experimental conditions is necessary to expand upon these results.”