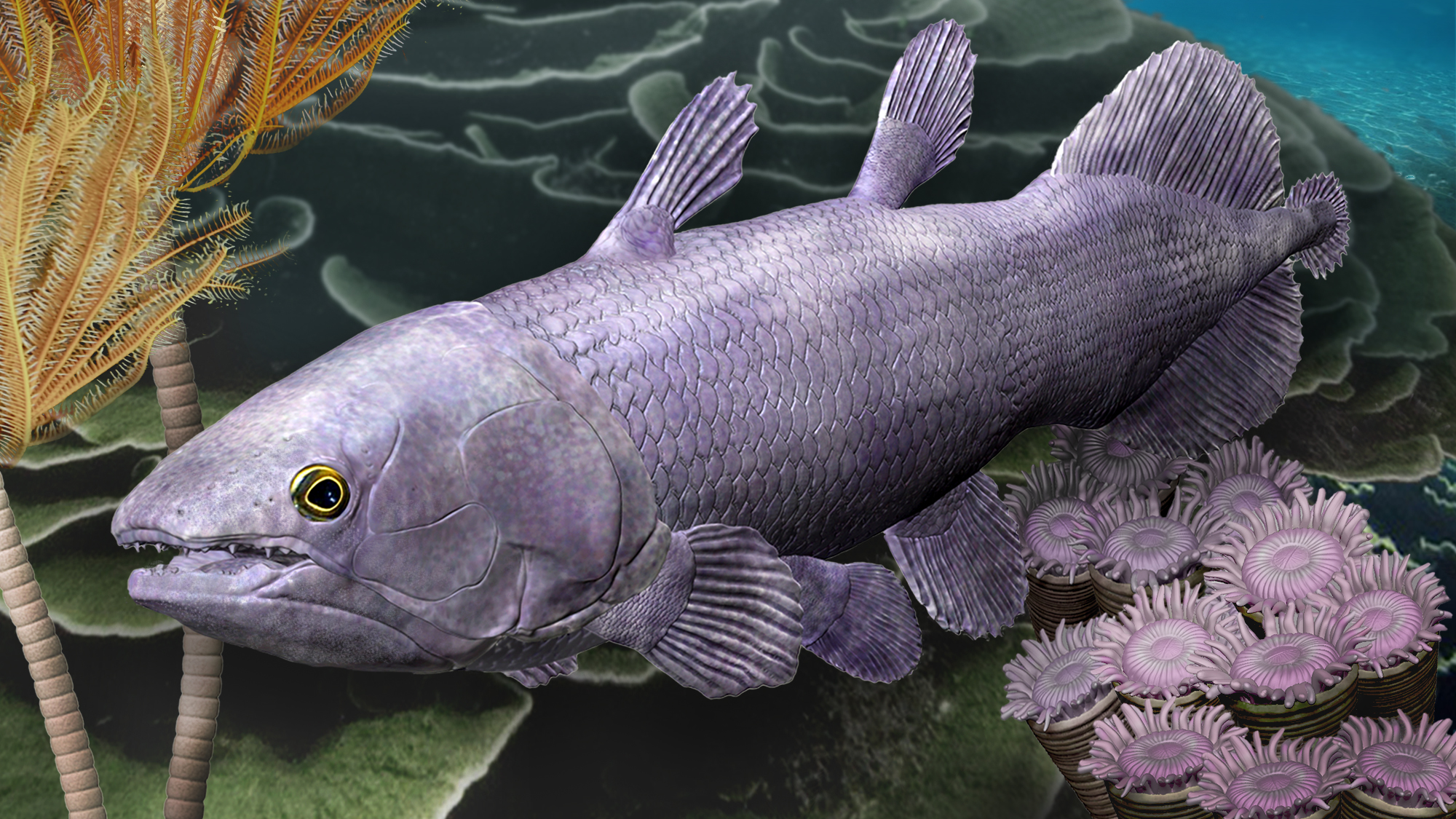

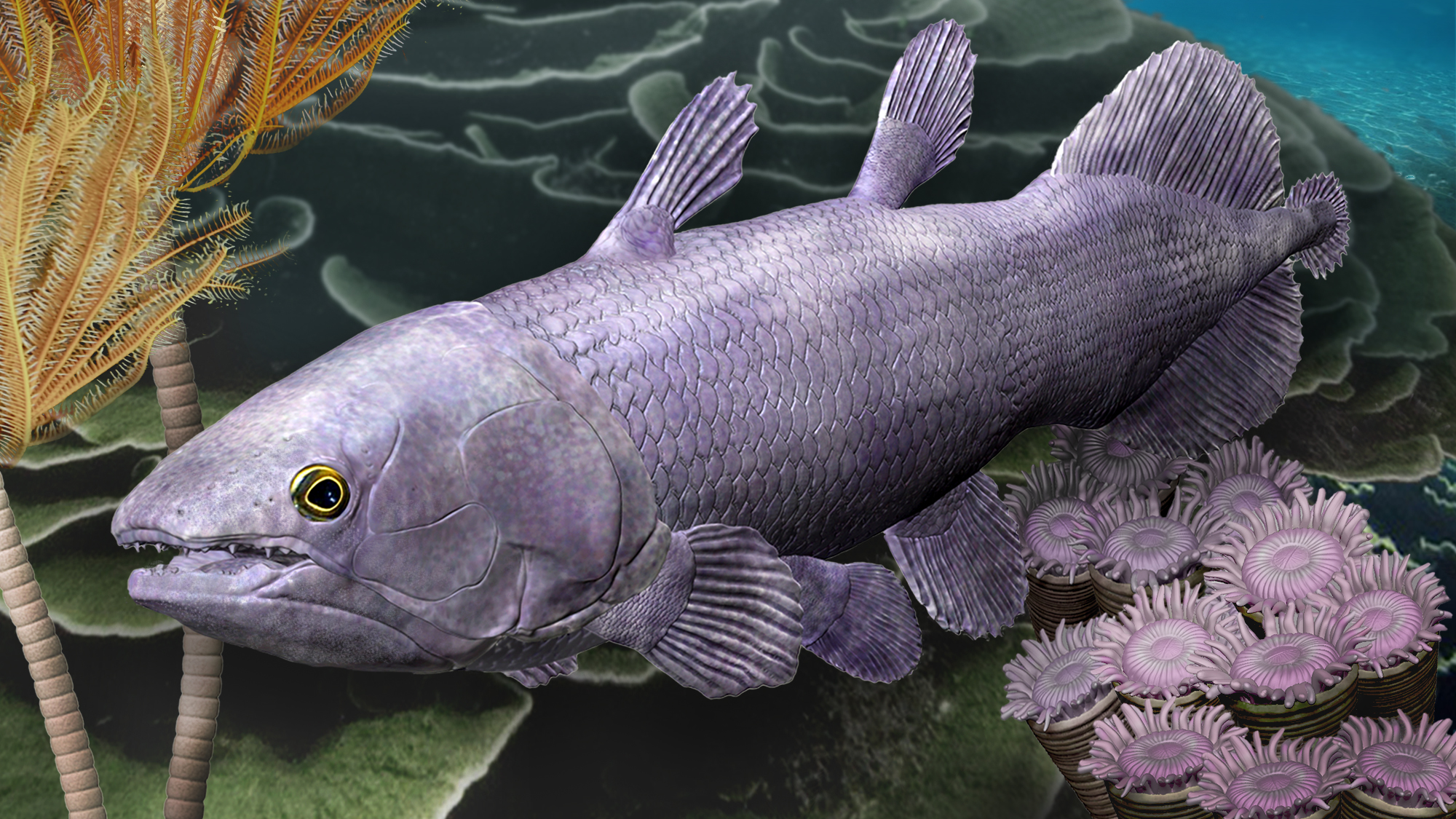

Paleontologists recently discovered a new extinct coelacanth species that highlights the role that Earth’s plate tectonics plays in evolution. Also called Latimeria, coelacanths are a deep-sea fish found off eastern Africa and Indonesia today.

This new “exceptionally well-preserved” ancient and primitive coelacanth is linked to a period of heightened movement of the Earth’s crust that likely rapidly sped up this fish’s evolution. Ngamugawi wirngarri also helps fill in an important transition between its earliest forms to its more evolved body. The findings are detailed in a study published September 12 in the journal Nature Communications.

“Our analyses found that tectonic plate activity had a profound influence on rates of coelacanth evolution,” Alice Clement, a study co-author and evolutionary biologist and palaeontologist from Flinders University in Australia, said in a statement. “Namely that new species of coelacanth were more likely to evolve during periods of heightened tectonic activity as new habitats were divided and created.”

[Related: Our four-legged ancestors evolved from sea to land astonishingly quickly.]

What is the Denovian mass extinction?

Plate tectonics appears to play a key role in how species on Earth evolve, the same way that events like changes in climate or asteroid impacts do. The new fossil of Ngamugawi wirngarri that points to this shaky time in Earth’s history was found in Western Australia’s Gogo formation. This formation includes fossils from numerous species that went extinct during the Devonian extinctions, a series of mass extinction events that occurred that primarily affected marine organisms about 359 to 419 million years ago.

While scientists are not entirely sure what led to the Devonian extinctions, it could have been rapid global warming or cooling, a meteorite strike, or excessive nutrient runoff from continental drift and plate tectonics. About 70 to 80 percent of all animal species went extinct, so the Denovian extinctions still ranks the lowest in severity of Earth’s major mass extinction episodes.

Coelacanth fossils like these are useful because two known coelacanth species are still alive today. They are likened to ‘living fossils’ due to their age and supposed similarities to ancient ancestors. Over the past 410 million years, more than more than 175 species of coelacanths have been discovered.

“[The fossil] provides us with some great insight into the early anatomy of this lineage that eventually led to humans,” study co-author and Flinders University paleontologist John Long said in a statement. “For more than 35 years, we have found several perfectly preserved 3D fish fossils from Gogo sites which have yielded many significant discoveries, including mineralised soft tissues and the origins of complex sexual reproduction in vertebrates.”

Coelacanths to humans

As a lobe-finned fish, the robust bones in coelacanth fins are somewhat similar to our own arms. They are also considered to be more closely related to lungfish and back-boned animals with arms and legs called tetrapods than they are to most other fishes.

Some parts of our own anatomy including jaws and chambered hearts have their roots about 540 to 350 million years ago during the Early Palaeozoic. In early fish, jaws, teeth, paired appendages, ossified brain-cases, intromittent genital organs, chambered hearts, and paired lungs all appeared at this time.

[Related: Yes, humans are still evolving.]

“While now covered in dry rocky outcrops, the Gogo Formation on Gooniyandi Country in the Kimberley region of northern Western Australia was part of an ancient tropical reef teeming with more than 50 species of fish about 380 million years ago,” said Long.

The team calculated the rates of coelacanth evolution. They found that coelacanth evolution has dramatically slowed down since the time of the dinosaurs, with some exceptions. During the age of dinosaurs, coelacanths diversified significantly, with some species developing unusual body shapes.

However, around 66 million years ago, they mysteriously vanished from the fossil record. This was during the end Cretacous mass extinction that wiped out approximately 75 percent of all life on Earth–including non-avian dinosaurs. Scientists assumed that coelacanth fishes had been a casualty of this same mass extinction event. In 1938, a group fishing off the coast of South Africa pulled up a large mysterious looking fish from the ocean depths that turned out to be a coelacanth.

It has since been touted as virtually unchanged, but the new fossil species is challenging the idea that surviving coelacanths have stopped evolving and are frozen in time.

“They first appear in the geological record more than 410 million years ago, with fragmentary fossils known from places like China and Australia. However, most of the early forms remain poorly known, making Ngamugawi wirngarri the best known Devonian coelacanth,” study co-author and University of Quebec in Rimouski vertebrate palaeontologist Richard Cloutier said in a statement. “As we slowly fill in the gaps, we can start to understand how living coelacanth species of Latimeria, which commonly are considered to be ‘living fossils,’ actually are continuing to evolve and might not deserve such an enigmatic title.”