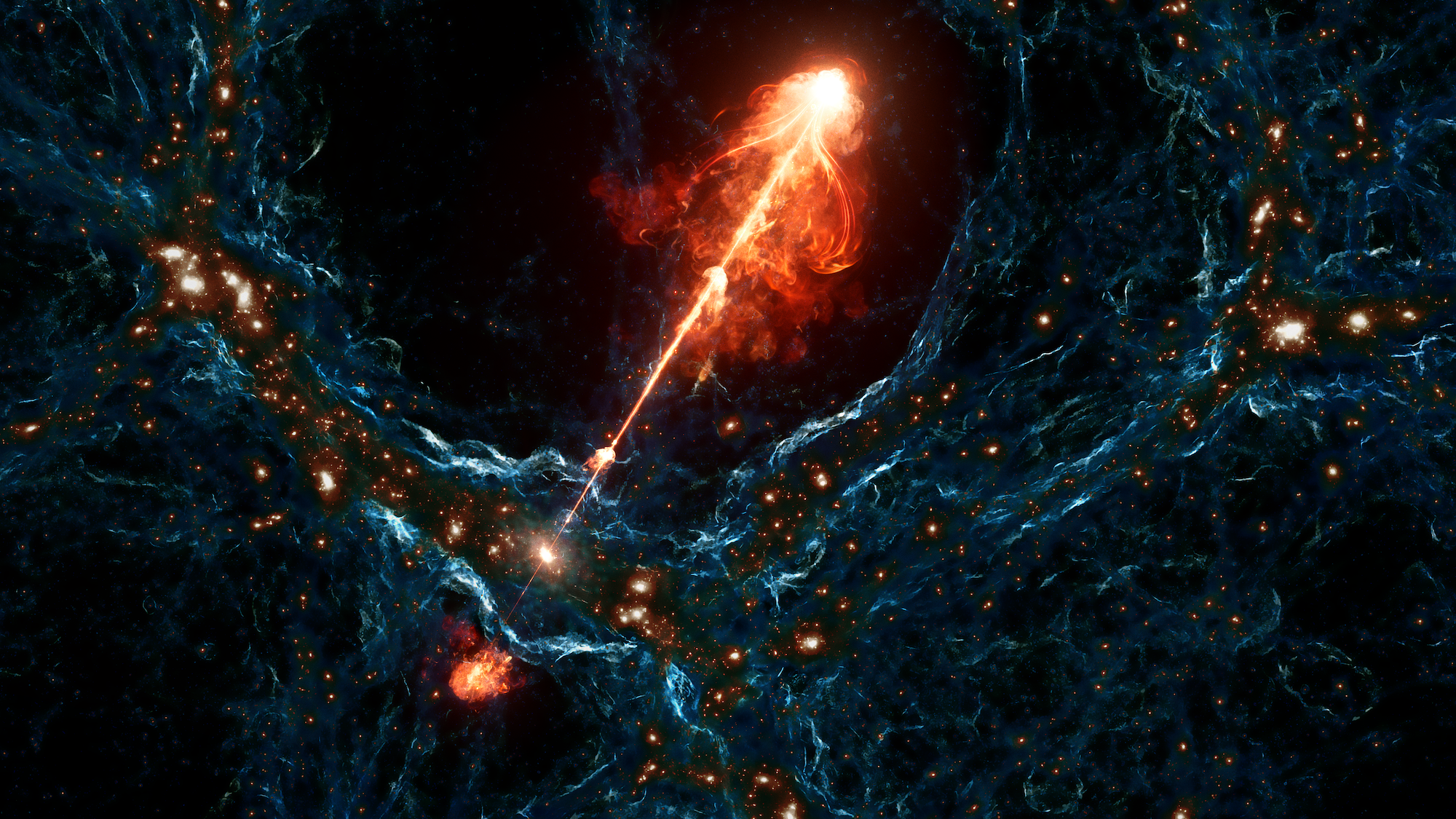

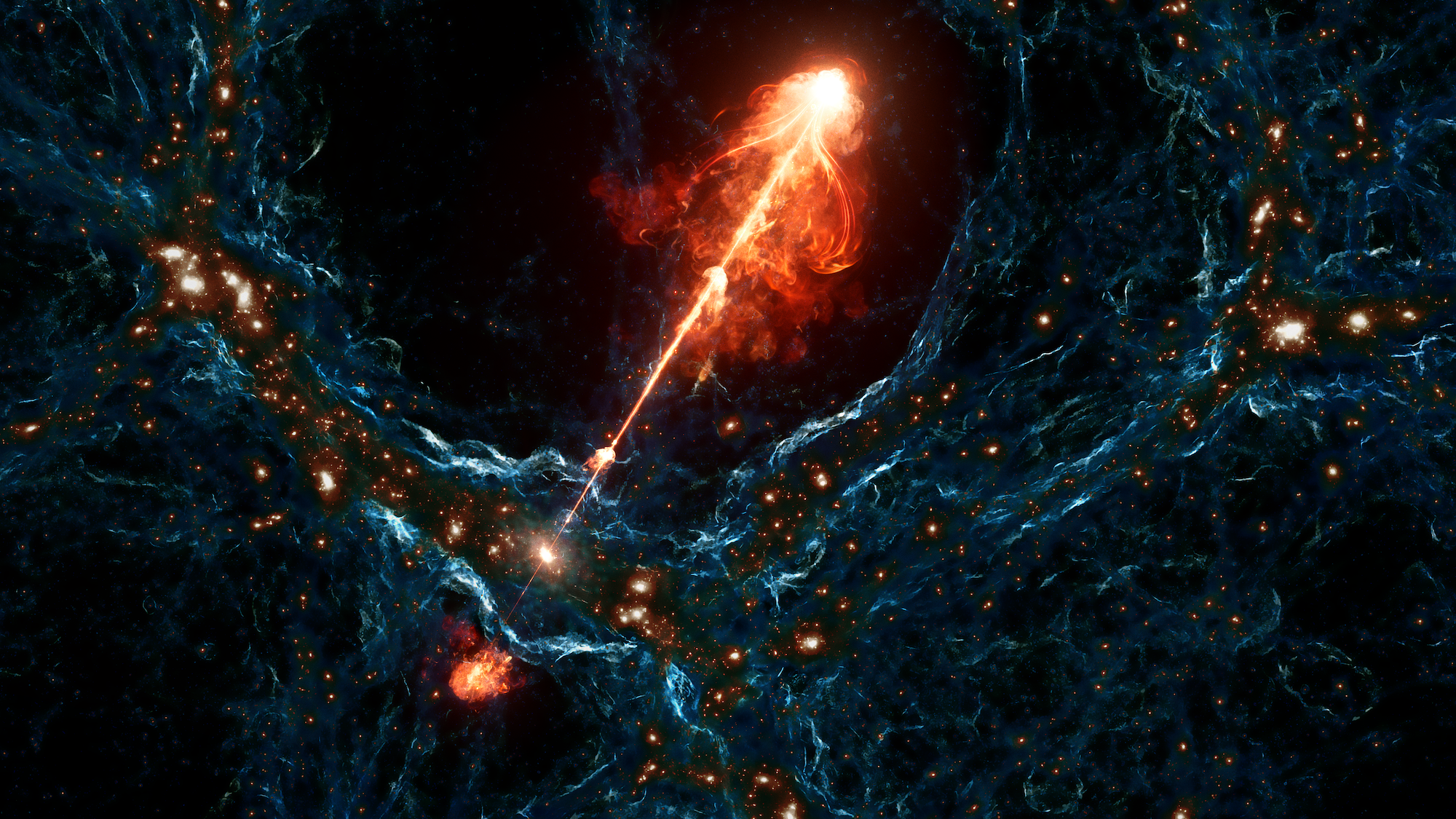

A newly discovered, distant duo of black hole jets is the largest of its kind ever seen. Formed when the universe was less than half its current age, the pair collectively spewed the energy equivalent of trillions of suns across 23 million light-years of space. Porphyrion, named after a giant from Greek mythology, is a cosmic megastructure that amassed when the universe was only 6.3 billion years old, and spans roughly the same distance of 140 Milky Ways. Astronomers say further studies could provide a window into how galaxies originated during the earliest eras of the universe. The findings, published on September 18 in the journal Nature, also indicate this may be only the “tip of the iceberg” for similar jet discoveries.

A snapshot back in time

Incomprehensibly vast distances separate Earth from most of the cosmos, but the celestial lights in the evening sky provide windows into the distant past. Images taken of Porphyrion today are technically snapshots of events that occurred 7.5 billion years ago, relatively speaking. Because of this, astronomers can use this information to expand their knowledge of the early universe’s foundational conditions, and how those influenced the creation of galaxies, stars, and planets.

“Astronomers believe that galaxies and their central black holes co-evolve, and one key aspect of this is that jets can spread huge amounts of energy that affect the growth of their host galaxies and other galaxies near them,” George Djorgovski, study co-author and Caltech professor of astronomy and data science, said in a statement.

Researchers have known that at least hundreds of black hole jet systems exerted at least some influence on early the universe’s evolution through the emission of cosmic rays, heavy atoms, magnetic fields, and heat. But it wasn’t until recently that they began to realize the scale of their importance. This shift came in recent years after employing Europe’s Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) radio telescope to survey the skies for supermassive black holes. The results have been nothing short of “shocking,” according to the team. By the time of Porphyrion’s discovery, over 10,000 black hole jet systems had been documented so far.

“Giant jets were known before we started the campaign, but we had no idea that there would turn out to be so many,” Martin Hardcastle, study second author and a University of Hertfordshire professor of astrophysics, said in the announcement. Hardcastle explains that although he expected to find more structures using LOFAR, “it was still very exciting to see so many of these objects emerging.”

When the giant Porphyrion formed

Porphyrion’s massive jets extend in polar directions from a supermassive black hole that lays in the center of a galaxy about 10 times the size of the Milky Way roughly 7.5 billion light-years from Earth. These deluges of energy extend around 40 percent further than the previous largest-known jet system, Alcyoneus, which the same team discovered in 2022 through LOFAR.

Porphyrion existed during an ancient era of the universe when the interconnected filaments of energy that feed into developing galaxies—known as the cosmic web—were closer than they are at present. Because of this, Porphyrion’s huge jets extended across larger areas of the cosmic web than they would today.

[Related: Astronomers discover Earth’s closest black hole.]

“Up until now, these giant jet systems appeared to be a phenomenon of the recent universe,” Martijn Oei, lead author and Caltech postdoctoral scholar, explained in a statement. “If distant jets like these can reach the scale of the cosmic web, then every place in the universe may have been affected by black hole activity at some point in cosmic time.”

spread across Europe. Credit: ASTRON

Yet another surprising realization about Porphyrion to astronomers was its “mode.” When a supermassive black hole’s gigantic gravitational forces begin to pull and heat surrounding material, they begin emitting energy as either radiation or in jets. Radiative-mode black holes were generally a staple of a young universe, whereas jet-mode versions are more common in the present. Despite its age and radiative-mode classification, Porphyrion still managed to emit enormous jets—indicating many similar, and possibly larger, megastructures may have existed at one time.

“We may be looking at the tip of the iceberg,” said Oei. “Our LOFAR survey only covered 15 percent of the sky. And most of these giant jets are likely difficult to spot, so we believe there are many more of these behemoths out there.”