Archaeologists often focus on what skeletal remains can tell about how and when ancient peoples died. But an individual’s final moments are far from their complete life story. By analyzing features like their teeth, researchers can better understand not only the person as an adult, but how they developed over the course of their life.

In Italy, a team at Rome’s Sapienza University has conducted the first dental study of its kind for an Iron Age community 35 miles south of present-day Naples. After analyzing the microscopic makeup of teeth from ancient Italians, it appears that the people living near Pontecagnano enjoyed a diverse diet that reflected a time of increased interactions with nearby Mediterranean societies. Their findings are detailed in a study published today in the journal PLOS One.

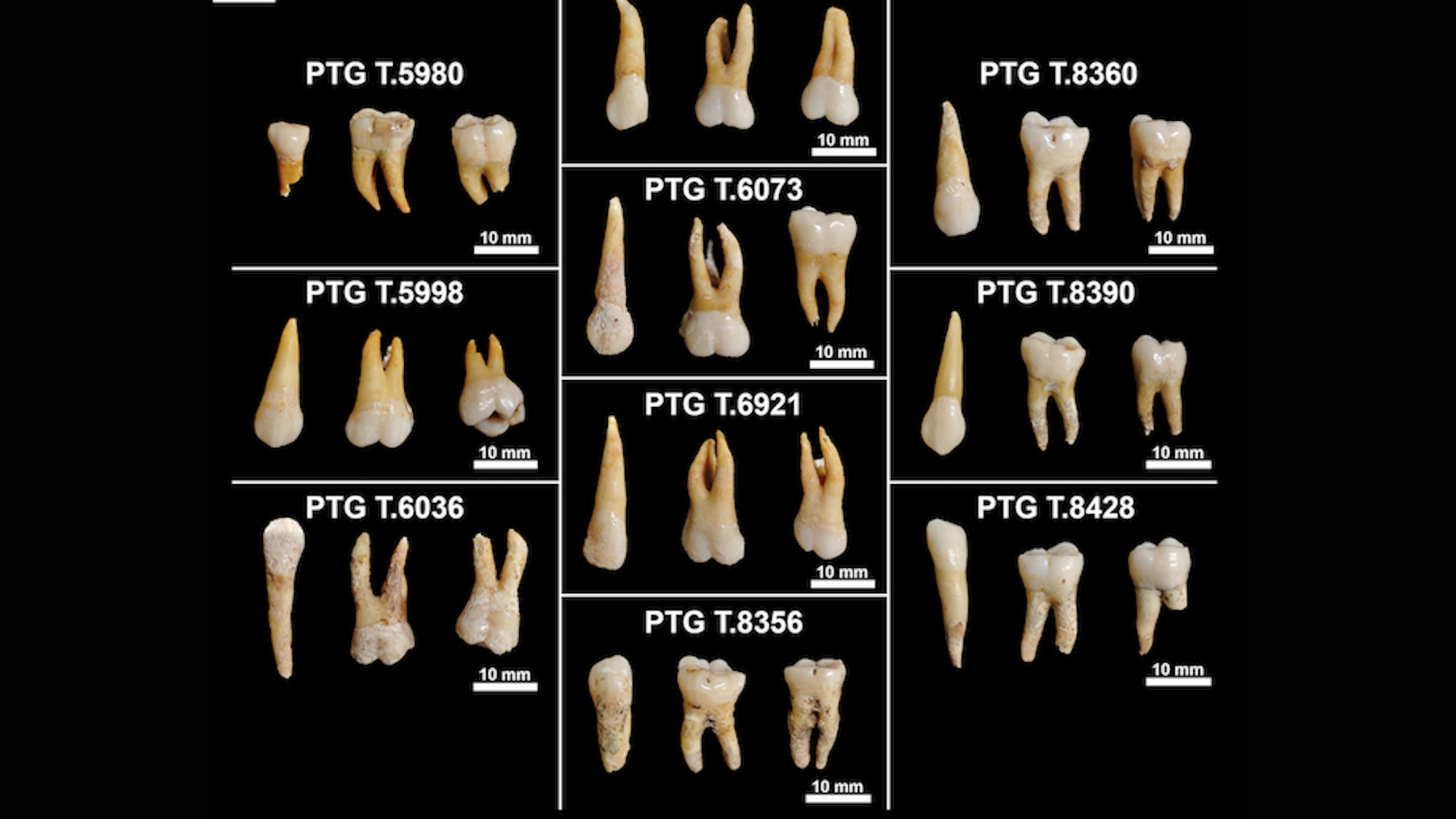

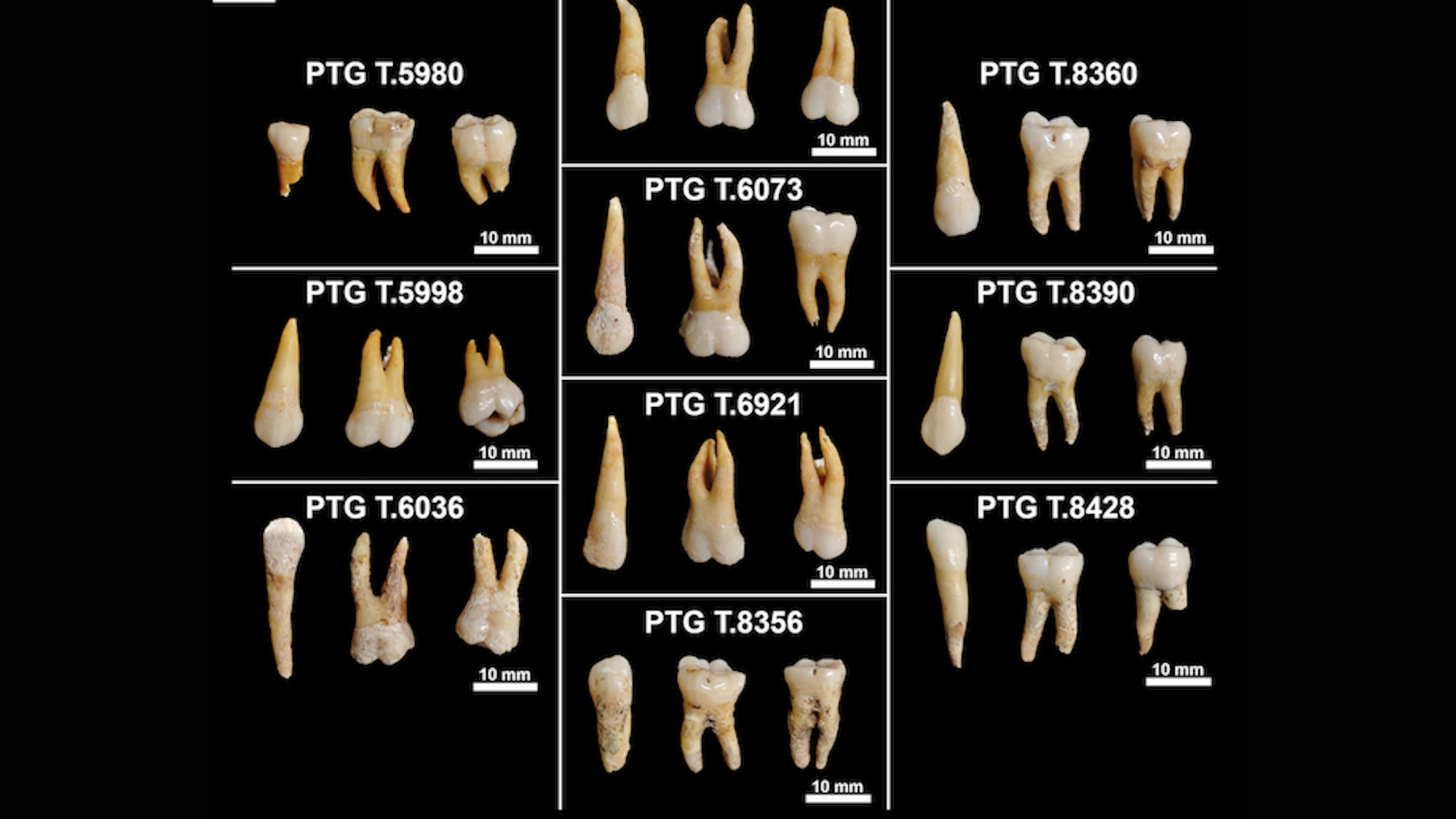

Archaeological records at Pontecagnano span multiple cultures and date as far back as the Copper Age (3500–2300 BCE). By the 7th century, the region was home to the Etruscans, who occupied the area until the Roman Empire’s arrival in the late 4th century. The Etruscans often interred their deceased in necropolises, which is where the Sapienza University team recovered 30 teeth from 10 individuals who died during the 7th and 6th centuries.

“The teeth of Pontecagnano’s Iron Age inhabitants opened a unique window onto their lives: we could follow childhood growth and health with remarkable precision,” study co-author and archaeologist Roberto Germano said in a statement.

They analyzed the growth patterns displayed in dental tissues, and then compared the resultant data between canines and molars to contextualize the first six years of each person’s life. This revealed minor stress events linked to dietary shifts, often between the ages of one and four. According to researchers, the changing sources of nutrition likely made the young children susceptible to diseases, which left lingering evidence in their teeth.

However, their diets were incredibly diversified by the time of adulthood. Dental plaque examinations showed remnants from an array of foods, including legumes and cereals as well as “abundant carbohydrates and fermented foods.” These chemical traces are supported by the existing historical understanding of the era, which featured increased trade with other societies around the Mediterranean.

The team believes that their approach represents a proof-of-concept for using dental analysis to offer personalized insights into the individual lives of ancient peoples. While not intended as findings representative of the larger Etruscan region, the analysis illustrates a more intimate look at Iron Age existence.

“The study…makes it possible to go beyond the narrow focus on the period close to their death, and brings to the forefront the life of each of them during their early years,” explained study co-author Alessia Nava.