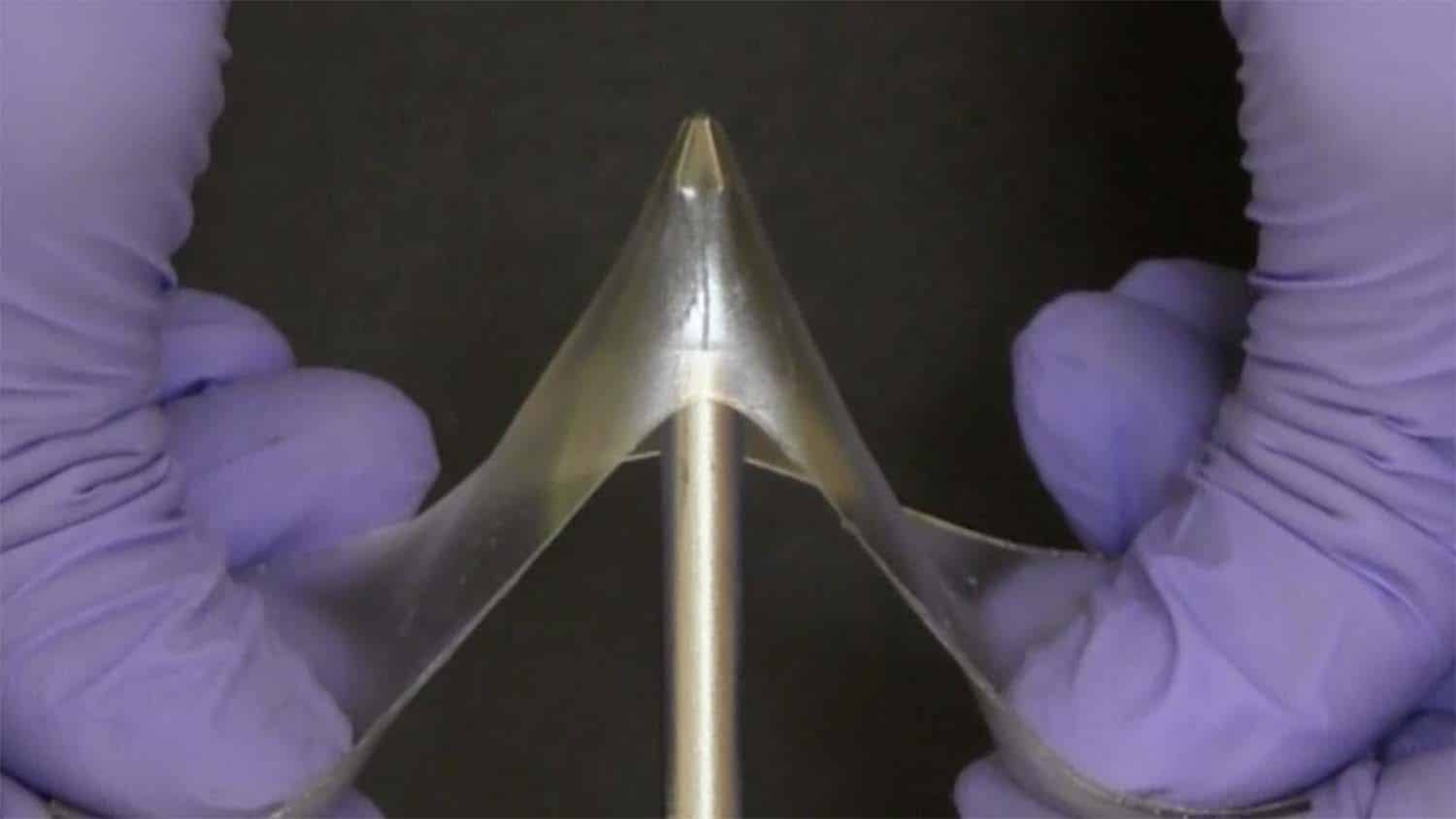

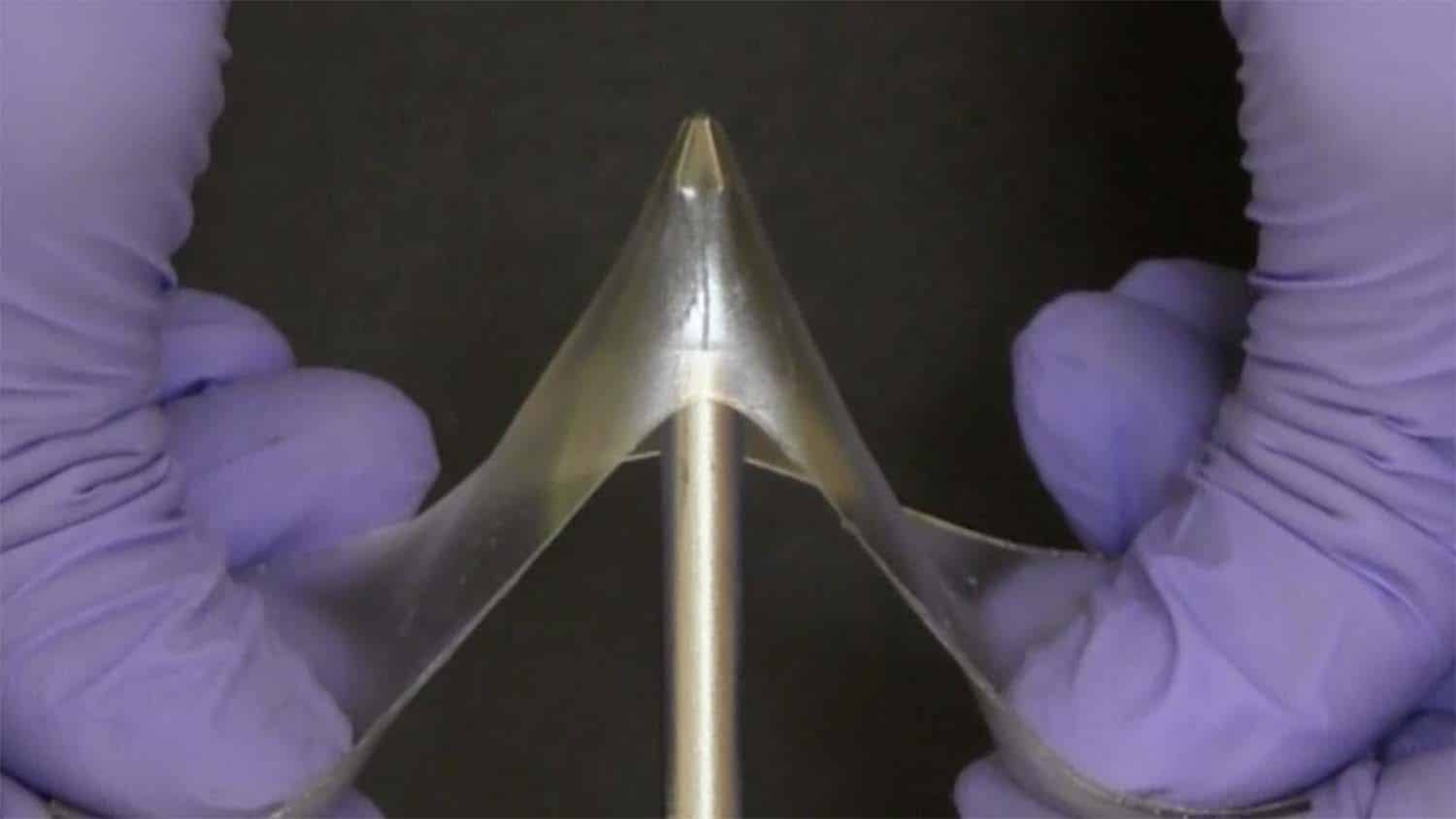

Super-elastic, self-healing “glassy gels” made from ionic solvents and polymers could one day become key components in 3D-printing and soft robots. And despite being composed of between 50-and-60 percent liquid, the new class of materials doesn’t dry out or evaporate, can withstand immense pressures, and stretch up to five-times their original shape without breaking.

Most people ditched hard, durable contact lenses years ago in favor of gel-based options for pretty understandable reasons—softer, liquid-infused gel polymers are far more comfortable, breathable alternatives than their glass predecessors. But after some recent lab experimentation, researchers at North Carolina State University have created a new material class combining some of the best properties of both options.

As detailed in a study published on June 19 in Nature, these glassy gels also possess unique adhesive qualities and conduct electricity more efficiently than common plastics with similar physical traits. According to its developers, the comparatively simple manufacturing process allows their glassy gels to cure in any mold or by using a 3D printer.

“Most plastics with similar mechanical properties require manufacturers to create polymer as a feedstock and then transport that polymer to another facility where the polymer is melted and formed into the end product,” Michael Dickey, a NCSU chemical and biomolecular engineering professor and paper corresponding author, said in an accompanying announcement.

To make a glass gel, however, Dickey and collaborators mixed a glass polymer’s liquid precursor with a liquid solvent made from ions. This solution is then poured into a mold and cured using ultraviolet light.

[Related: New, lightweight polymer is stronger than steel.]

“Normally when you add a solvent to a polymer, the solvent pushes apart the polymer chains, making the polymer soft and stretchable. That’s why a wet contact lens is pliable, and a dry contact lens isn’t,” Dickey explained. “In glassy gels, the solvent pushes the molecular chains in the polymer apart, which allows it to be stretchable like a gel. However, the ions in the solvent are strongly attracted to the polymer, which prevents the polymer chains from moving.”

This inability to move makes the gel glassy and hard, yet still stretchable when needed. While multiple polymers can be used to make glassy gels, Dickey also noted that charged or polar polymers are the most effective since they’re attracted to ionic liquids. But although the researchers know how such ionic attractions work, the reason why their glassy gels are adhesive remains a bit of a mystery.

“[It is] maybe the most intriguing characteristic,” Dickey said. “… Because while we understand what makes them hard and stretchable, we can only speculate about what makes them so sticky.”

While still in their early development, the team is confident the glassy gels could hold a lot of promise across manufacturing and engineering applications, and are actively looking for new collaborators.