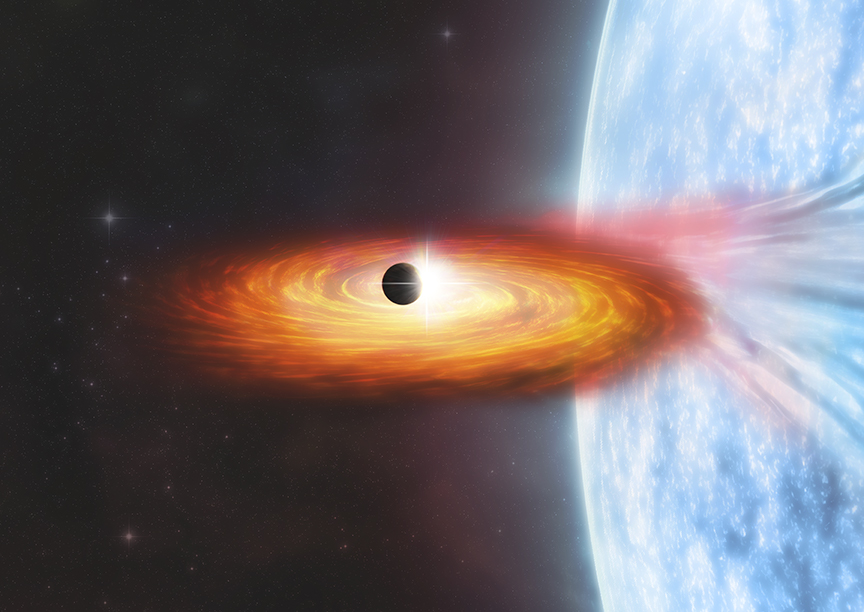

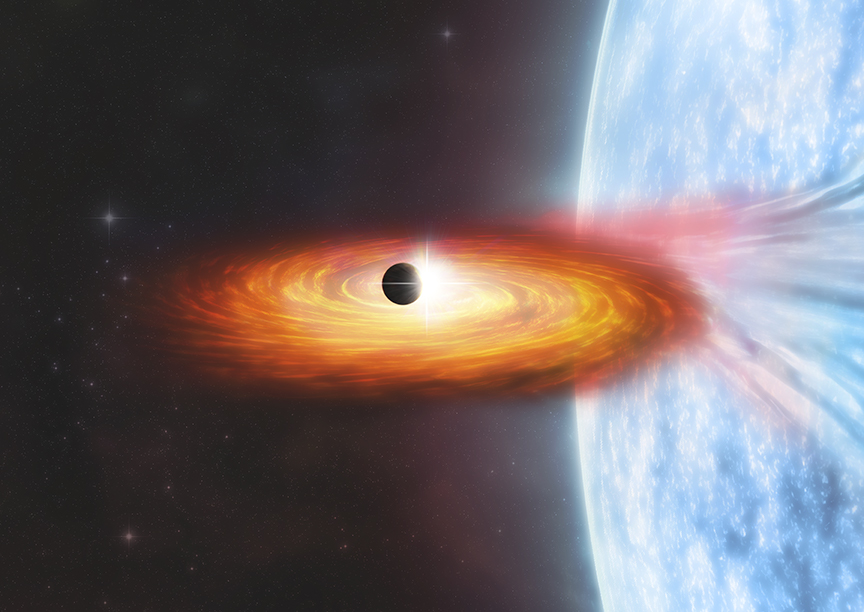

For the first time, astronomers have detected evidence of a planet in a galaxy beyond our own. The yet unnamed exoplanet lies in the Messier 51, often referred to as the “Whirlpool” galaxy, around 28 million light-years from Earth.

Astronomers and planetary scientists have discovered nearly 5,000 exoplanets so far, but all were found within the confines of our own Milky Way galaxy. The new discovery is the first to detect and place a planetary body in an entirely different galaxy—a feat achieved by using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory telescope to observe “transit,” when a planet passes in front of a star and blocks its rays. The findings were published this week in Nature Astronomy.

“We are trying to open up a whole new arena for finding other worlds by searching for planet candidates at X-ray wavelengths, a strategy that makes it possible to discover them in other galaxies,” Rosanne Di Stefano, Harvard University astrophysicist and leader of the study, said in a NASA statement.

Most exoplanets have been found in transit by observing dips in optical light as a planet passes in front of a star, but Di Stefano and her team instead looked for dips in x-rays. Regions where x-rays can be detected are small but bright, and this technique could allow astronomers to find exoplanets at much greater distances than with current optical light transit studies.

[Related: A newly discovered planet orbiting a dead star offers a glimpse of Earth’s future]

Though an exciting find, scientists still need to confirm the evidence—a process that, in this case, will take decades. The potential new planet won’t cross in front of its star for another 70 years, giving astronomers a long and undetermined wait before they can confirm the findings.

“Unfortunately to confirm that we’re seeing a planet we would likely have to wait decades to see another transit,” said co-author Nia Imara, a University of California at Santa Cruz astrophysicist, in the NASA statement. “And because of the uncertainties about how long it takes to orbit, we wouldn’t know exactly when to look.”

That uncertainty with timing has other planetary scientists wondering how useful this method of detecting x-ray transits is and how often it should be used. Bruce Macintosh, a Stanford University astrophysicist who wasn’t involved with the research, told NBC that studying X-ray transits is “clever,” but since “you can only see transits when objects line up just right between you and the thing you’re looking at” (and those alignments only ever last a couple hours at most) it’s unlikely that it could be used to find hundreds of thousands of planetary candidates.

But Di Stefano told NBC that she’s excited that this new method, which she and her colleagues first proposed in 2018, yielded such exciting results in the search for extragalactic exoplanets. “We did not know whether we would find anything, and we were extremely lucky to have found something,” she said. “Now we hope other groups around the world study more data and make even more discoveries.”