A team of paleontologists recently found matching sets of Early Cretaceous dinosaur footprints on what are now two different continents. One set is in Brazil and the other is roughly 3,700 miles away in Cameroon. Over 260 footprints show where terrestrial dinosaurs were last able to freely walk between Africa and South America millions of years before the two continents split apart. The findings were published on August 23 by the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science.

“We determined that in terms of age, these footprints were similar,” study co-author and Southern Methodist University paleontologist Louis L. Jacobs said in a statement. “In their geological and plate tectonic contexts, they were also similar. In terms of their shapes, they are almost identical.”

[Related: A newly discovered sauropod dinosaur left behind some epic footprints.]

Studying footprints–or trace fossils–like these is important because they offer clues to how quickly dinosaurs and other organisms walked or ran and even what their skin may have looked like. Compared with the more well-known body fossils of teeth or bones, trace fossils often contain evidence of how these long-dead animals interacted with their environment and can also indicate what their environment may have looked like.

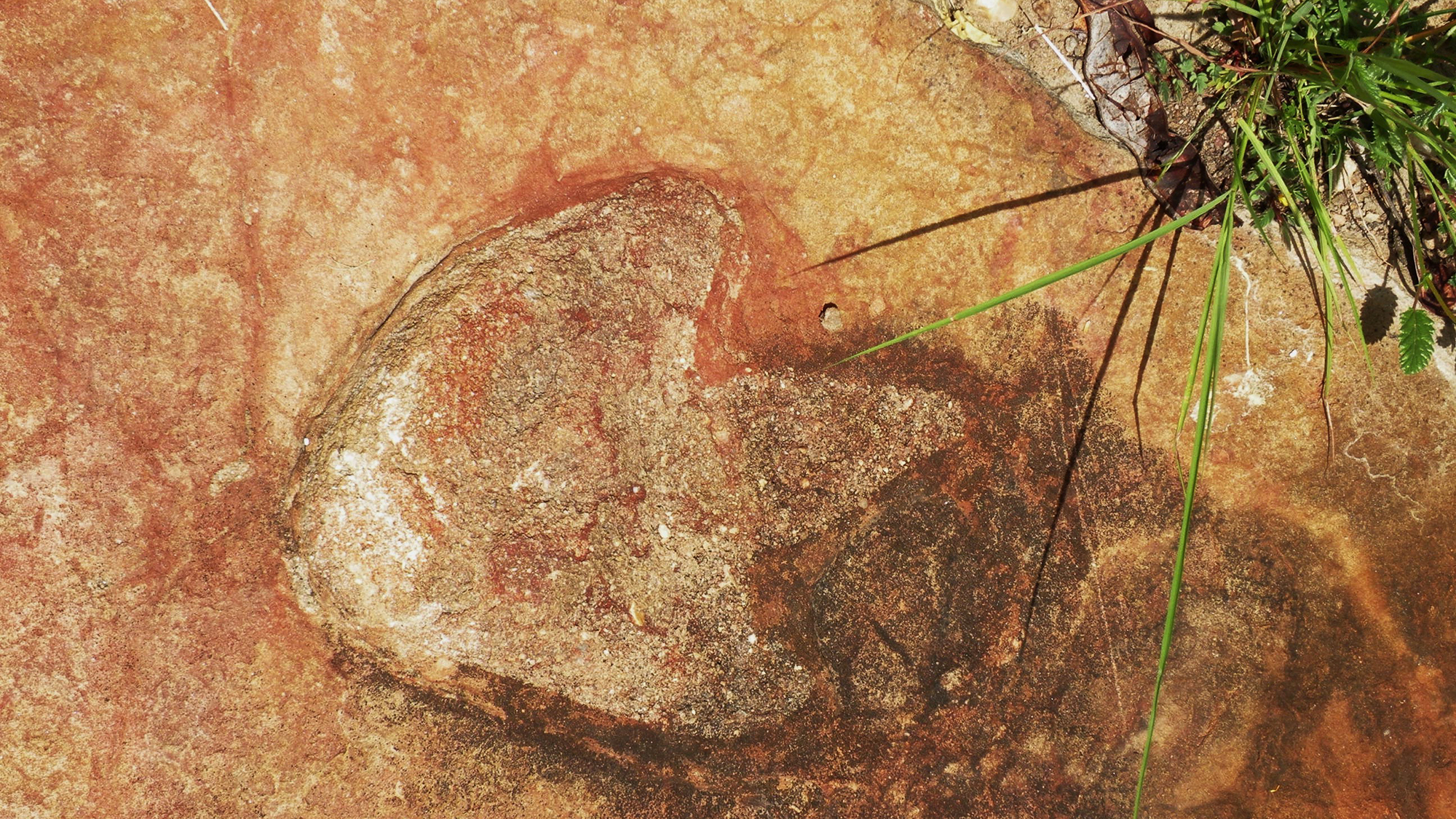

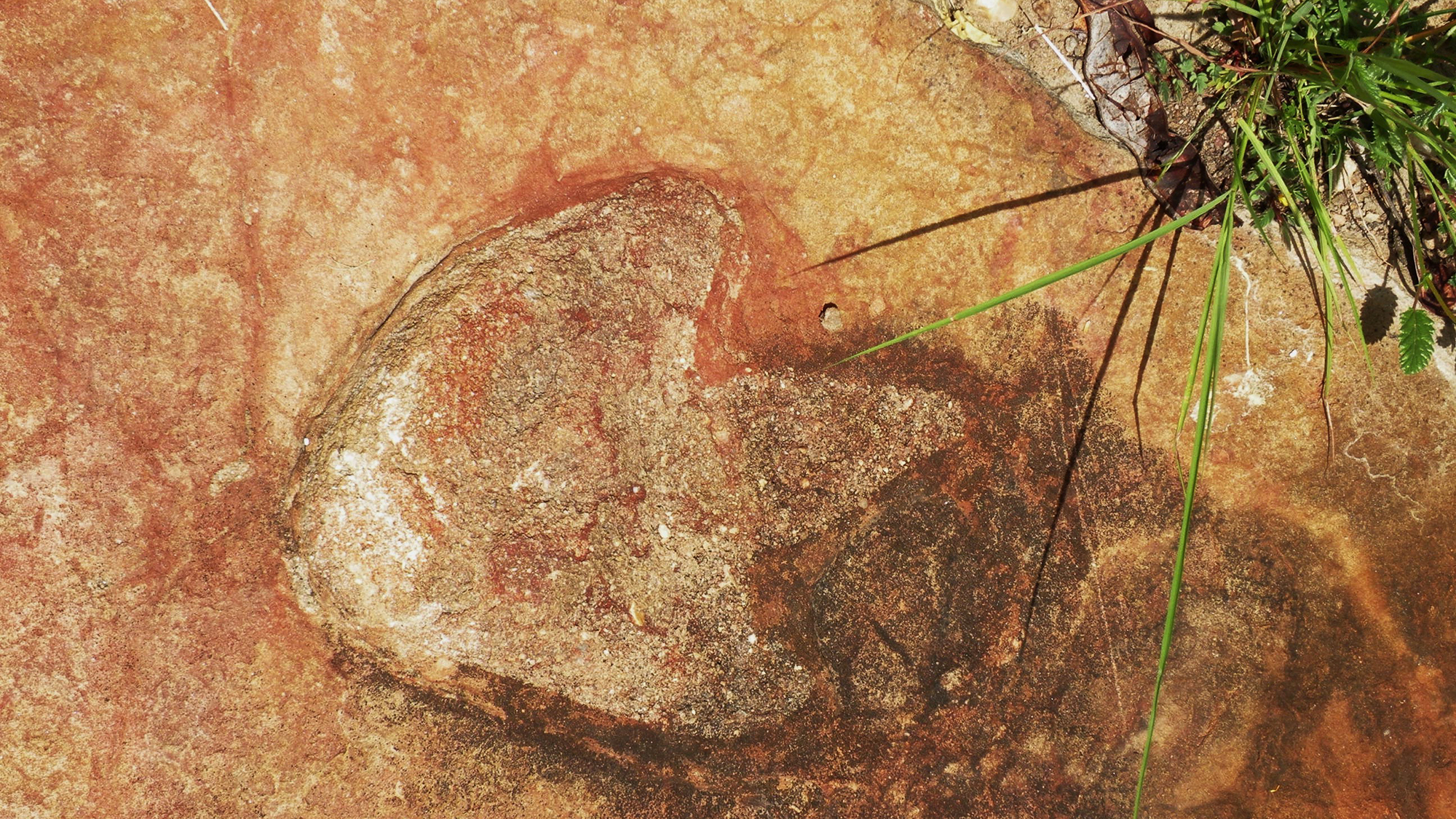

The team believes that most of the footprints were created by three-toed theropod dinosaurs. A few were also probably made by sauropods or ornithischians. The footprints are impressed into the mud and silt along a few ancient rivers and lakes and were made 120 million years ago on a single supercontinent known as Gondwana. This supercontinent broke off of the larger landmass Pangea. Just before the connection between Africa and South America was fully severed, lakes formed between the basins.

“Plants fed the herbivores and supported a food chain,” said Jacobs. “Muddy sediments left by the rivers and lakes contain dinosaur footprints, including those of meat-eaters, documenting that these river valleys could provide specific avenues for life to travel across the continents 120 million years ago.”

South America and Africa began to split apart about 140 million years ago. This break up caused huge gashes in the Earth’s crust called rifts to open along any pre-existing weaknesses in the crusts. As the tectonic plates beneath the two continents moved apart, magma from the Earth’s mantle rose to the surface. The magma forged a new oceanic crust, while the continents moved away from each other. Eventually, the South Atlantic Ocean filled in the void between these new continents.

[Related: Why dinosaur footprints inspired paleontologist Martin Lockley.]

The South American footprints were found in the Borborema region in northeast Brazil. The African footprints were discovered in Koum Basin in northern Cameroon. Some geological signs of when the continents split apart are present in both locations where these dinosaur footprints are located. Geologic structures that formed as the Earth’s crust pulled apart called half-graben basins were present in both areas. These basins have ancient river and lake sediments and fossil pollen that indicate the area is about 120 million-years-old.

“One of the youngest and narrowest geological connections between Africa and South America was the elbow of northeastern Brazil nestled against what is now the coast of Cameroon along the Gulf of Guinea,” said Jacobs. “The two continents were continuous along that narrow stretch, so that animals on either side of that connection could potentially move across it.”

The article was also a tribute to the late paleontologist Martin Lockley, who spent the bulk of his career studying dinosaur tracks and footprints.