Alcohol distilled in a replica of a disgraced emperor’s 2,000-year-old bronze vat may help rewrite China’s drinking history. Although famous medical texts like the 16th century Ming Dynasty’s Bencao Gangmu originally cited the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368 CE) as the earliest evidence of Chinese alcoholic distillation, recent experiments conducted by a team affiliated with Zhengzhou University support a theory that pushes back that estimate by as much as 1,000 years.

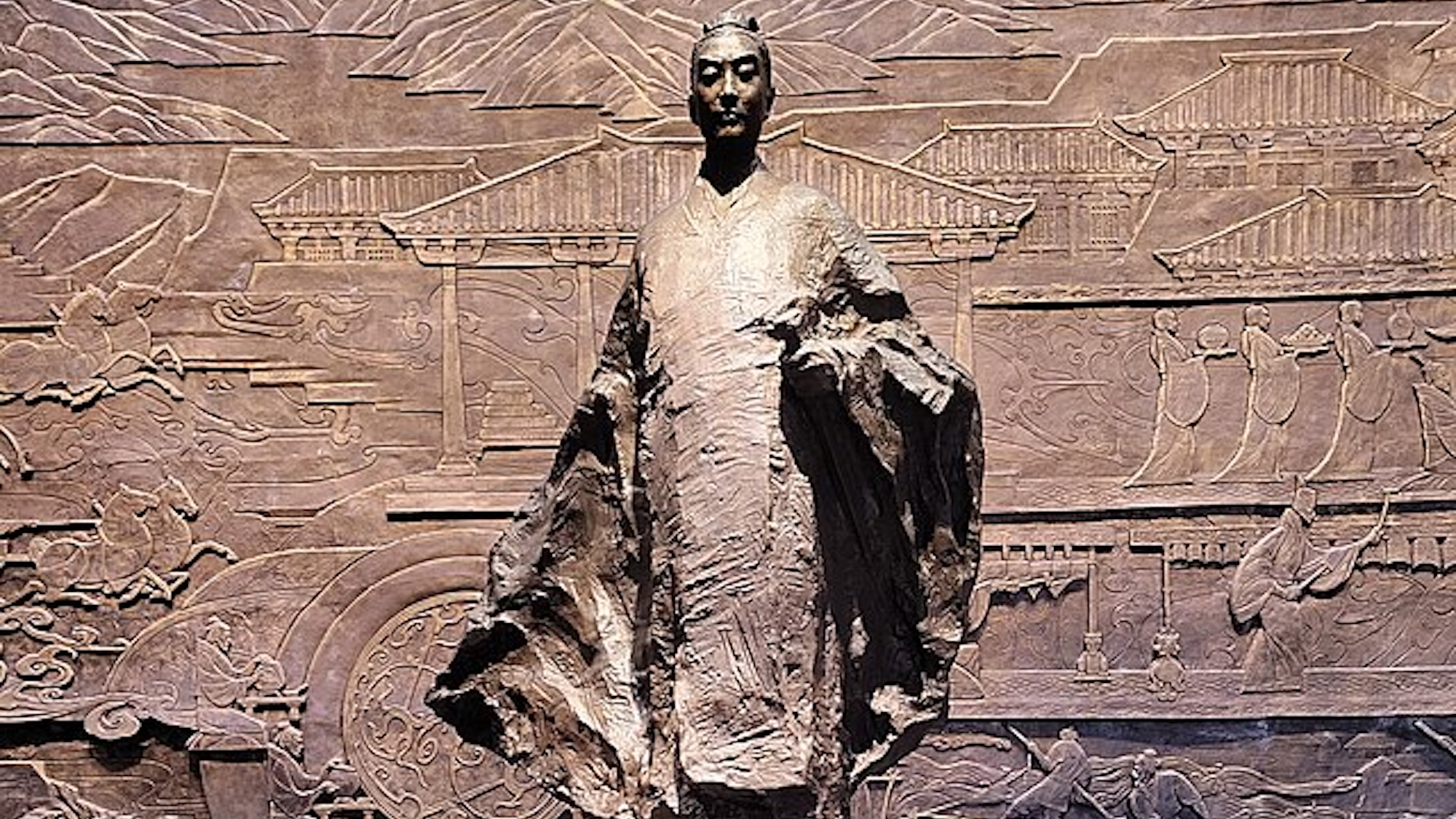

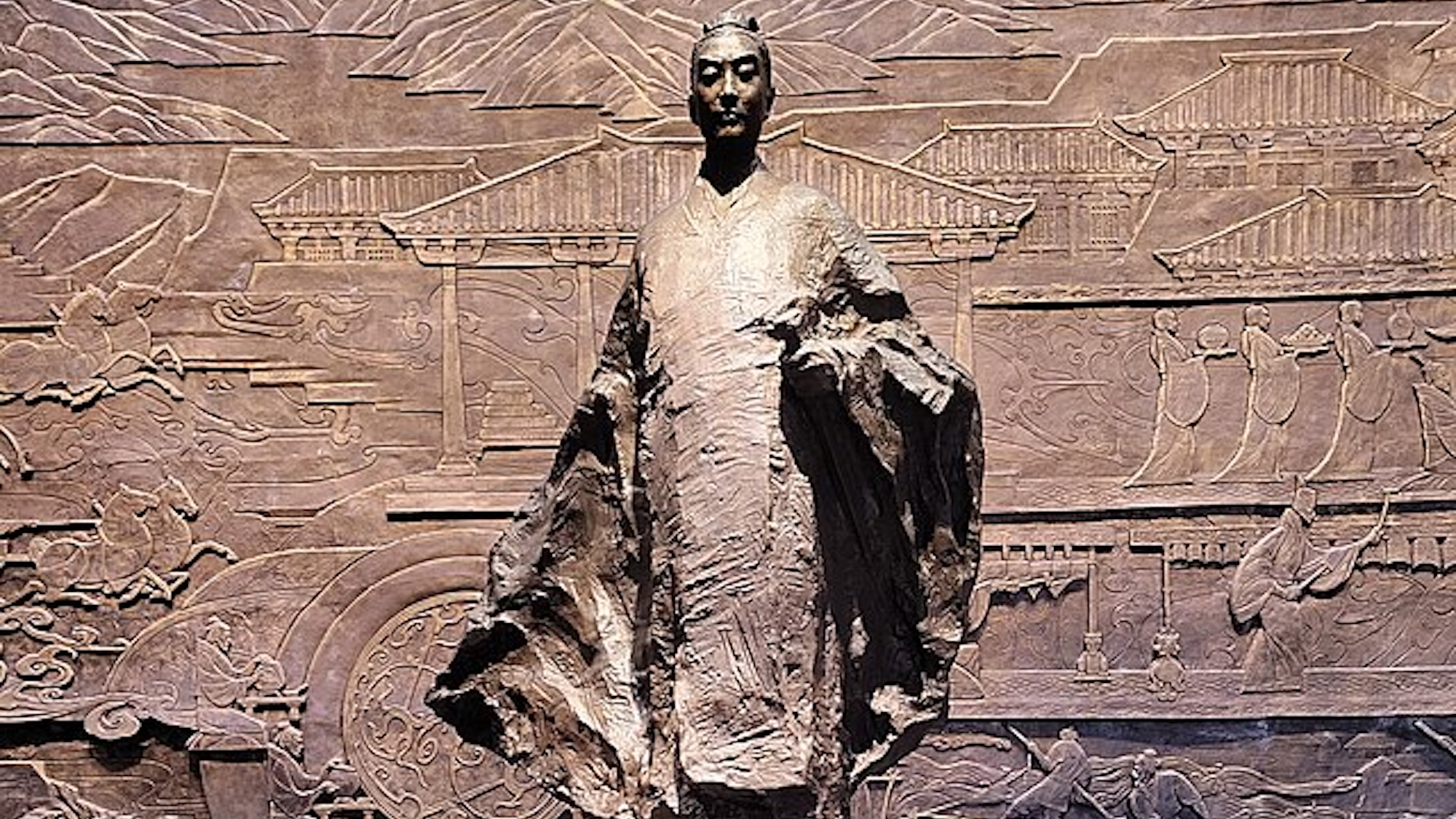

As Arkeonews explained on January 1st, the 1:2 scale replica is based on a metal vessel recovered from the tomb of Emperor Liu He, one of the most well-preserved gravesites from the Western Han dynasty (202 BCE-9CE). Liu He’s tenure on the throne as the dynasty’s ninth emperor was short-lived, however—opponents (including his wife, the Empress Dowager Shanggua) conspired to overthrow and exile him just 27 days into his reign due to impropriety and incompetence in 74 BCE.

According to his articles of impeachment, Emperor He wracked up 1,127 misconduct charges, including failing to abstain from meat and sex during a period of mourning, failing to keep the imperial safe secure, and nepotism. Court historians ultimately omitted Liu He from the kingdom’s official list of emperors, and his overthrowers exiled him to become the Marquis of Haihun in what is now the Jiangxi province. The deposed Western Han politician ultimately died in 59 BCE.

Despite his infamy, He’s tomb remained remarkably well-preserved until its rediscovery by archeologists in 2011. The trove of grave relics included the oldest known Chinese painting of Confucius, as well as around 6,000 composite armor scales made from lacquered leather, iron, and copper. But it was a unique, bronze distillation array found in the tomb that caught the attention of Zhengzhou University researchers and the country’s State Administration of Cultural Heritage.

Distillation is the process of concentrating alcoholic liquid into more potent, often flavor-rich liquors like brandy, whisky, and bourbon. This is usually achieved through boiling a fermented liquid such as wine or corn mash. The resultant steam travels through an apparatus that separates the alcoholic liquid from its fermented ingredients, after which the former byproduct is collected for further development and eventual consumption. The three-part contraption found in He’s tomb included a main vat known as the “heavenly pot,” a cylindrical unit, and a brewing cauldron.

Although some experts believed He’s distiller was used to purify and concentrate cinnabar and flower dews, others theorized the setup could also have been for distilling alcoholic drinks like wine into brandy-like beverages. To test out the hypothesis, a team led by tomb excavation project manager and archeologist Zhang Zhongli built a half-sized replica of the artifacts and followed ancient distillation recipes that included ingredients like taro from around the same time period. Zhongli’s team then used yellow wine and beer to achieve a 70 percent distillation efficiency while maintaining each source liquid’s flavor and alcohol concentration.

“This discovery is remarkable. It has recreated this product from the Western Han dynasty—from the selection of raw materials, to the production process, and the instrument,” Zhongli told the South China Morning Post last month.

According to collaborator Yao Zhihui, the previous flower dew purification theory can also be “ruled out” due to the original distiller’s design, as well as residue analysis conducted at the excavation site. If nothing else, Liu He’s laundry list of transgressions—including feasting and gaming—arguably support the theory that the exiled emperor also enjoyed his alcohol.