Human performance—be it artistic, academic, social, or otherwise—is often influenced by the size of the crowd around them. But we aren’t the only species that adjusts to an audience. According to recent research, some of our closest animal relatives display the same crowd-induced performance boosts and limitations depending on crowd size. The new evidence indicates these innate psychological influences date back to well before the evolution of human cultures that valued reputation and authority.

It’s already well known that chimpanzees organize themselves into hierarchical societies, but experts previously disagreed on how much their peers may influence their emotions, actions, and performance capabilities. But as a study published on November 8th in the journal, iScience, details, even chimps appear susceptible to the “audience effect” in certain social situations.

[Related: Chimp conversations can take on human-like chaos.]

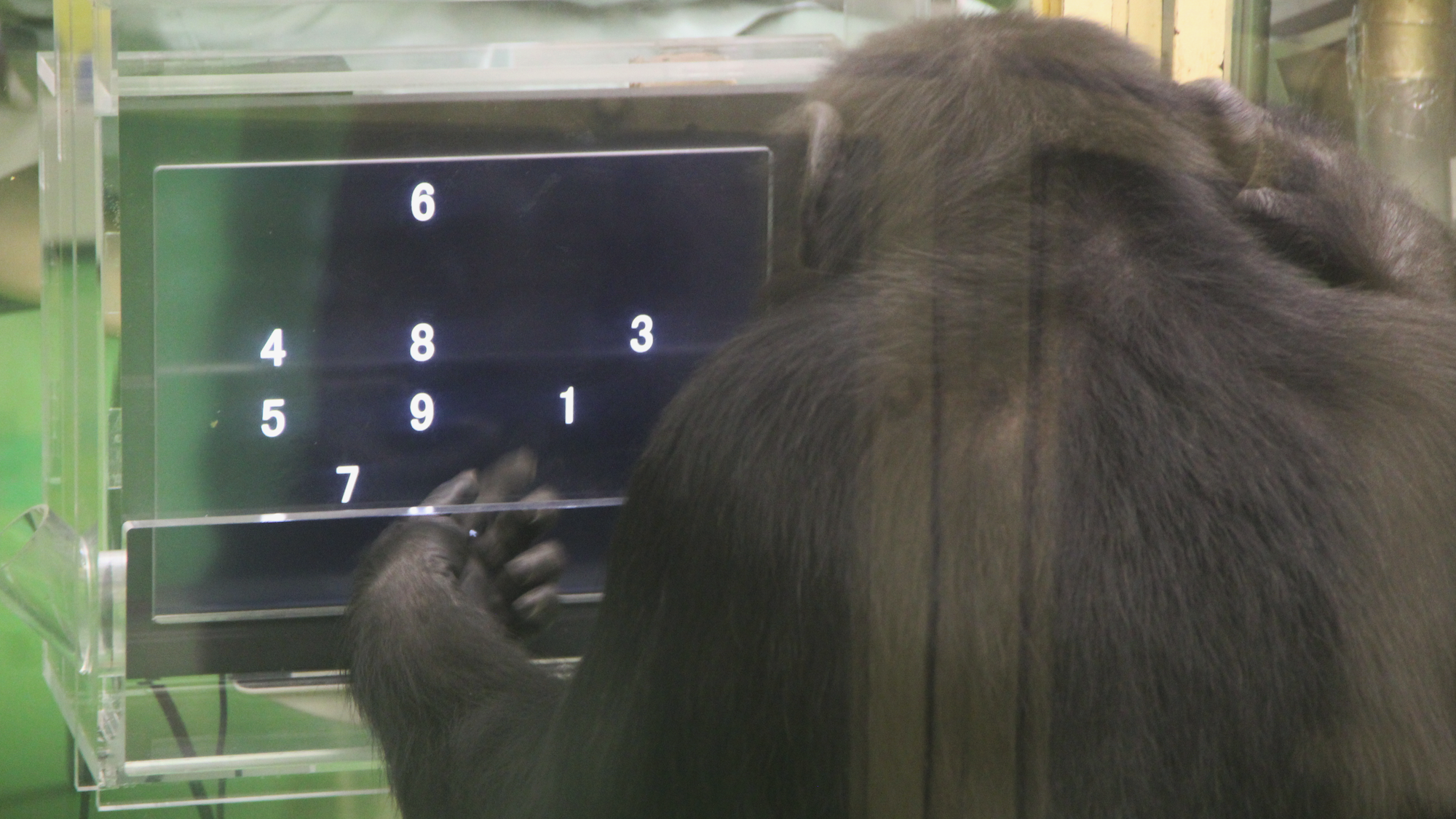

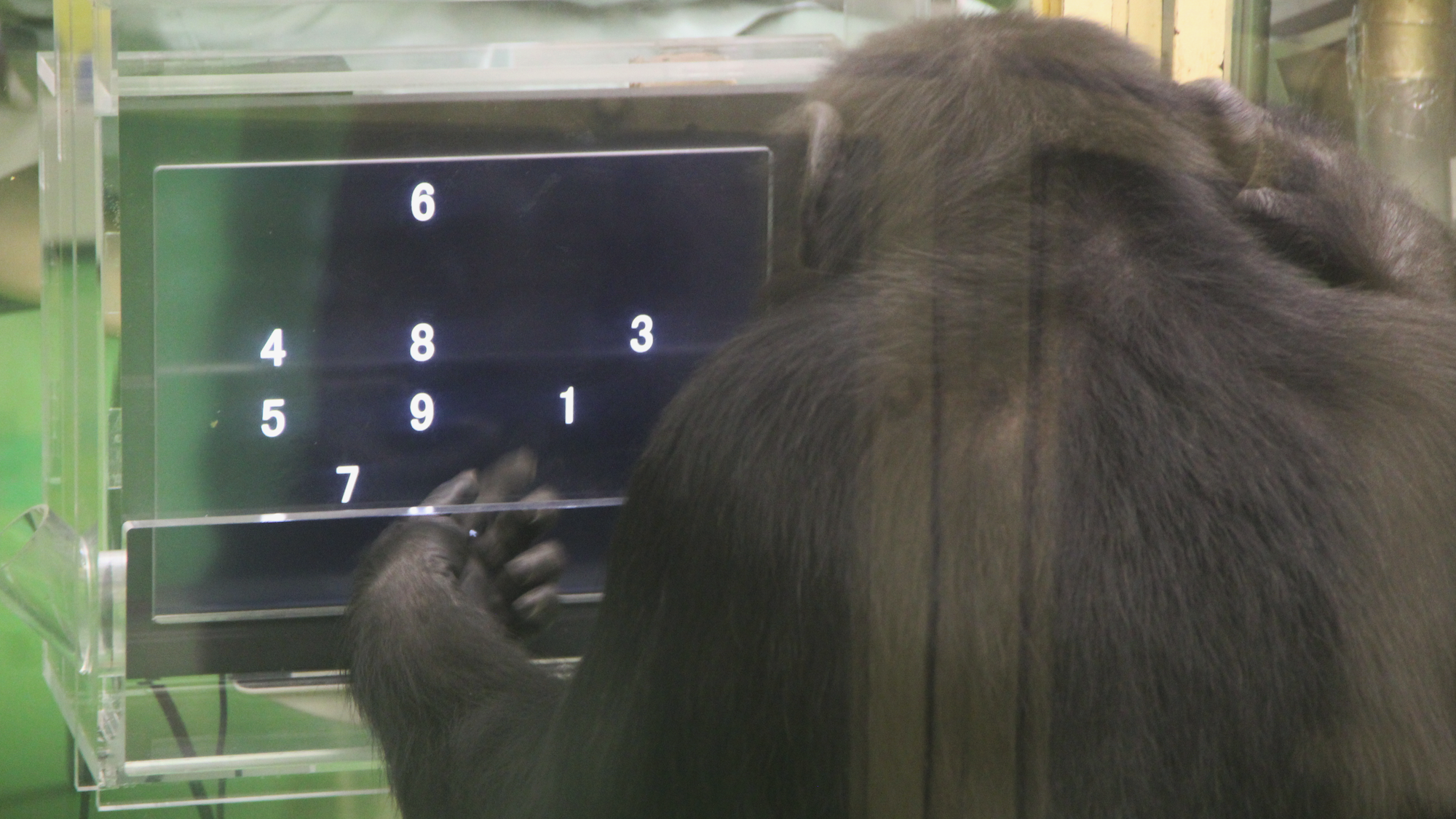

To assess how this effect manifests in chimps, researchers at Japan’s Kyoto University relied on their study facility’s comparatively unique environment. There, chimps interact with humans on a nearly daily basis through the use of touch screen-based, food reward experiments. Because of this, the team offered six chimpanzees three different, numerical-based touch screen tasks that varied in complexity and cognitive requirements.

In the first task, chimps needed to touch numbers 1-19 sequentially after they appeared in adjacent order on their screen. The second game again required the animals to select the numbers in order, but only after the numerals displayed in disparate places across the screen. Task three, the most difficult, had chimps select the numbers in order once more. This time, however, all other numbers would disappear when the primates pressed a single digit, requiring them to quickly memorize the positions in real-time. Researchers then analyzed each primate’s performance results collected from thousands of sessions over six years of testing.

Reviewing the data identified two particular trends. Chimps’ average performances improved by a “statistically significant” amount on their most difficult task in tandem with an increased number of fellow experimenters. But for the easiest task, the animals performed worse if they knew more chimps or familiar humans were standing nearby.

“Our findings suggest that how much humans care about witnesses and audience members may not be quite so specific to our species,” Shinya Yamamoto, a study co-author at Japan’s Kyoto University, said in a statement on Friday. “… [I]f chimpanzees also pay special attention towards audience members while they perform their tasks, it stands to reason that these audience-based characteristics could have evolved before reputation-based societies emerged in our great ape lineage.”

Study co-author Christen Lin added that while one might not expect a chimp to care if another species watches them performing a task, “the fact that they seem to be affected by human audiences even depending on the difficulty of the task suggests that this relationship is more complex than we would have initially expected.”

The team noted that they still aren’t certain what neurological mechanisms trigger these behavioral changes in both primates and humans. Still, they hope that further studies of our ape relatives may help one day better explain these shared, cross-species experiences.