Astronauts of the future trekking their way across barren extraterrestrial landscapes may soon do so with less fear or running out of water—or uncomfortably shuffling through their own pee—thanks to a new Dune-inspired urine filtration system. The small, backpack-like device, created by researchers from Cornell University and detailed today in Frontiers in Space Technology, could help explorers conduct lengthier space missions without the need for heavy, cumbersome water reserves. It could also help modernize astronaut’s current approach to dealing with biological waste, which essentially amounts to a large adult diaper.

The new device would use a small silicone catheter to immediately identify and absorb an astronaut’s urine. An onboard integrated reverse and forward osmosis system would filter out toxins and store the remaining liquid as safe, drinking water. If successful, researchers say the novel filtration system would provide astronauts with a “continuous supply of potable water” that could allow them to explore their environments without having to lug around heavy water reserves. That simplified mobility could come in handy, especially as NASA plans for several manned moon missions in coming years that place scientific exploration at the forefront.

Astronauts have too much pee and not enough water

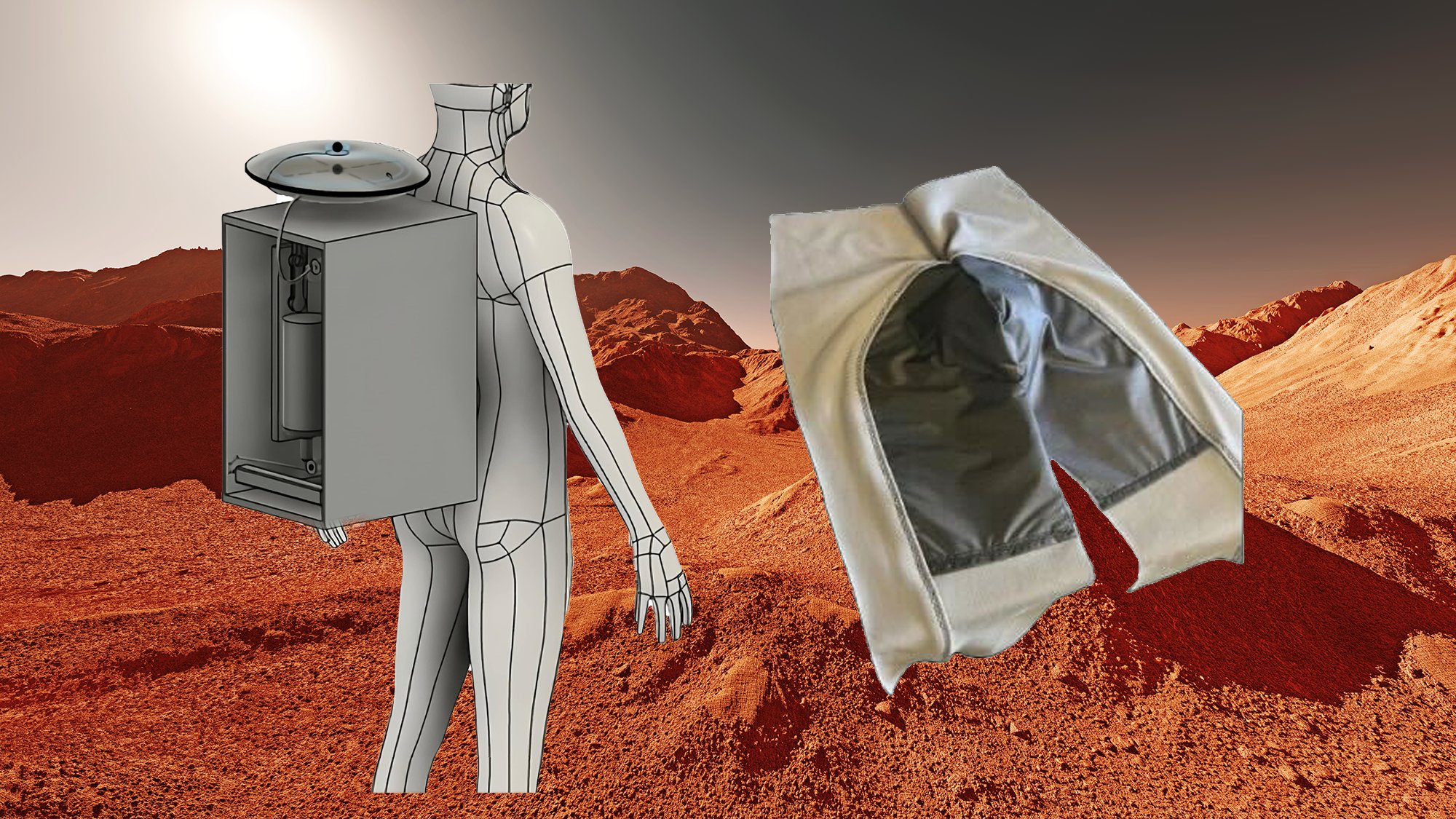

The process for relieving oneself during a spacewalk isn’t glamorous. Current spacesuits feature what’s called a “Maximum Absorbency Garment,” (MAG) that can retain around 300 times its weight in fluids. MAGs, which despite their abbreviated title are essentially highly absorbent diapers, can hold around two liters of urine, blood, and feces. That might sound like a lot until one realizes just how much time space explorers may have to spend away from a toilet. Astronauts are expected to have around seven urinations a day and a typical spacewalk for repairs or scientific research, on average, lasts six and a half hours. (Excursions topping out over eight hours aren’t unheard of either).

To put it mildly, many astronauts aren’t thrilled about the idea of conducting that crucial, often high-stakes work with a sagging bottom. In some cases, researchers say astronauts have opted to eat smaller, calorie light meals to cut down on the amount of waste created in their suit. But that strategy can simultaneously impair their ability to perform at their mental and physical best. Prolonged time spent in a filthy MAG diaper also inherently increases the odds of skin irritation or even infection.

“This is undoubtedly an environment not conducive to optimal performance or the maintenance of heath,” the researchers write.

But wet diapers are only half of the problem. Spacewalks are physically demanding operations and can easily lead to dehydration if astronauts aren’t properly hydrated. Current spacesuits come equipped with an In-Suit Drink Bag (IDB) filled with just 32 ounces of water. Past simulations of astronauts responding to a hypothetical rover failure in space resulted in the astronauts chugging through 50%-100% of their allocated water supply. And that’s just now. Future planned Artemis missions to the Moon and Mars will require astronauts to spend far greater lengths of time on spacewalks and exploratory missions than they do currently. They will need access to much more water to survive in those environments.

“Astronauts currently have only one liter of water available in their in-suit drink bags,” Weill Cornell Medicine and Cornell University Research Staff Member Sofia Etlin said. “This is insufficient for the planned, longer-lasting lunar spacewalks, which can last ten hours, and even up to 24 hours in an emergency.”

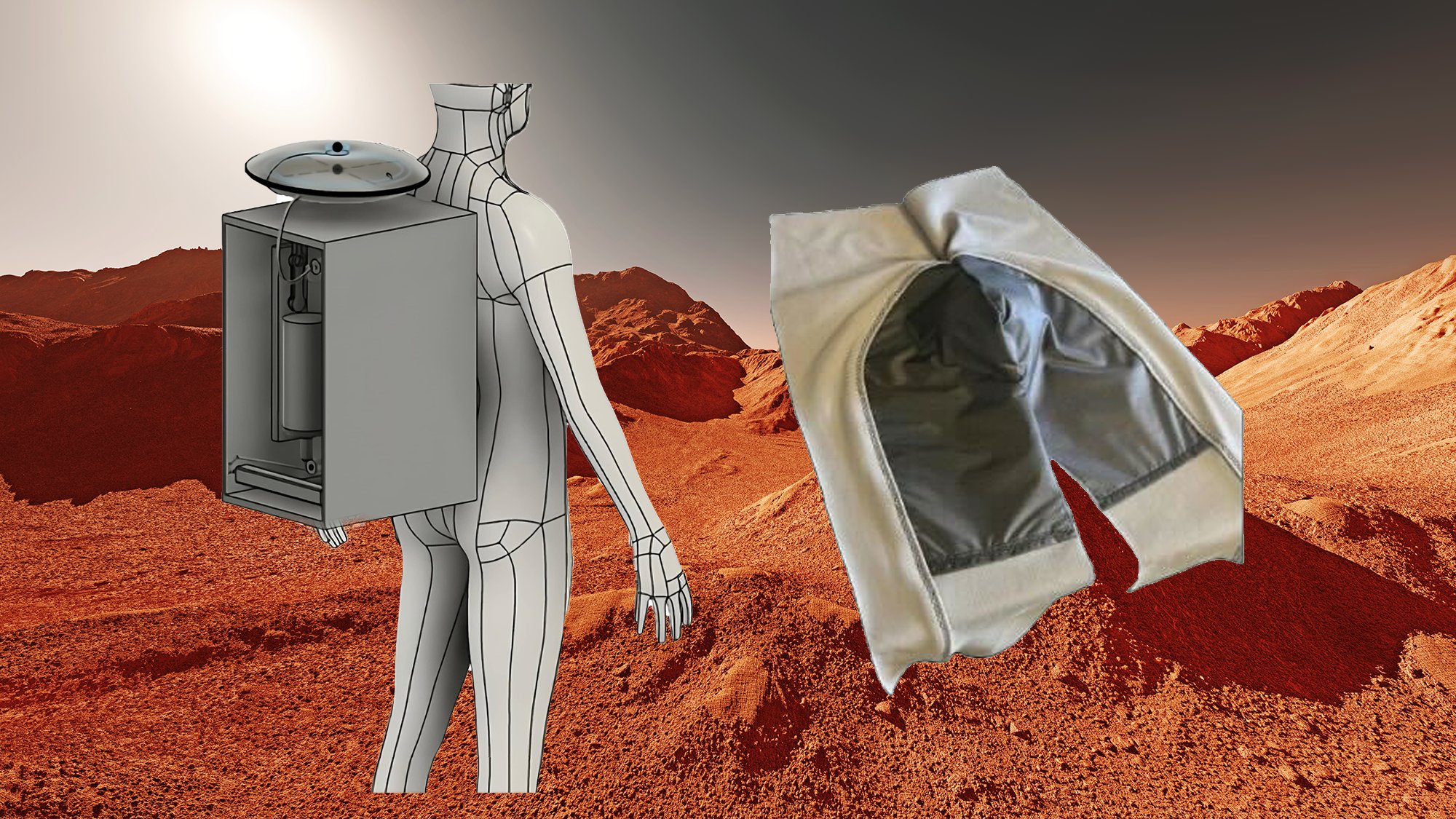

The Cornell researchers believe they may have found a solution with a prototype “Urine Collection Device” (UCD) that could help address both of those problems at the same time. The device would absorb exuded by astronauts, filter it, and then add back in nutrients to create viable drinking water. The process notably would not apply to feces or sweat. All told, the entire process of filtering a typical urination of 100-500mL should take under five minutes. If any of that sounds familiar, it’s probably because the device sounds similar, in concept, to the “stillsuits” used in Frank Herbert’s 1965 sci-fi novel turned Hollywood blockbuster Dune. In that case, the novel’s Fremen are clad head-to-toe in fabric and tubes capable of turning moisture into highly valuable water. The UCD is modest by comparison. Shaped like a rigid backpack, the device has an area of 38X23 and adds eight kilograms (17 pounds) of additional weight.

How a urine filtration device would work

In practice, the new filtration system would replace the previous diaper with several layers of fabric meant to easily allow for the passage of urine. Unlike the previous MAG system, which is intended to absorb copious quantities of urine, the UCD needs to do the opposite and absorb as little plant liquid as possible. Astronauts using the new system would wear a gender specific silicone external catheter that resembles a “cup” some athletes wear atop their genitals. An RFID tag attached to an absorbent hydrogel uses a humidity detector to know when the cup is filled with liquid. When the up is full, a vacuum pump is triggered to move the urine into the filtration device.

Once initiated, the pee passes through an antimicrobial fabric layer before being pumped to limit the amount of contact it may have with an astronaut’s skin. The device then uses an integrated forward and reverse osmosis system to filter out salt and other solutes from the urine. The resulting purified water is finally enriched with electrolytes and pumped back into the suit’s drink bag, where the astronaut can take a sip. Researchers say the filtration system recycles the urine to water with an efficiency of 85% and a minimum of 75% water recovery. That entire process is powered by a 20.5 volt battery.

Initial prototyping for the UCD is already underway. Cornell University Professor of Physiology and Biophysics and study lead author Christopher Mason says the device can be tested in simulated microgravity conditions similar to what future Artemis astronauts might experience. And while the device does add additional weight and battery considerations that could complicate a spacesuit, the researchers argue the tradeoff in terms of hygiene and water storage are “well worth it.”

This actually isn’t the first instance of some trying to realize some elements of Dune-style stillsuits. Just last month, engineers from the YouTube channel Hacksmith Industries used a combination of personal protective equipment (PPE) and spare computer parts to create a suit capable of somewhat effectively transforming the wearer’s sweat into drinkable water. In that case, the engineers used a thermoelectric cooler embedded into the suit to turn the surrounding moisture into a liquid. Neither the Hacksmith prototype nor the UCD filtration device are one-to-one stand ins for the types of suits featured in Dune but the are both proof theoretical designs once reserved to the dense pages of sci-fi literature could play a role in reimagining real-world scientific endeavors.