As a rule, almost anything that involves the prefix neuro is probably a buzzword. Brains! They’re the key to everything! Pretty pictures of brain scans or electrical pulses can reveal the depths of the human experience! We’re even more likely to believe poor explanations of psychology when they’re accompanied by gratuitous neuroscience jargon.

Perhaps no field is buzzier than neuromarketing, a concept invented in the 1990s by Harvard psychologists and now used by companies like Google, Frito-Lay and CBS. Neuromarketers operate on the principle that simple focus groups and surveys aren’t enough to truly figure out what people want–marketing needs to tap into the subconscious parts of the brain. Marketers need to know what you want before you want it. And so neuromarketers co-opt the techniques of neuroscience–analyzing the brain’s responses to products with electroencephalography (EEG) and MRI imaging. Brain-whispering, The New York Times called it a few years ago.

Now, Matt Wall argues over at Slate that neuromarketing doesn’t produce solid data–and perhaps it never can.

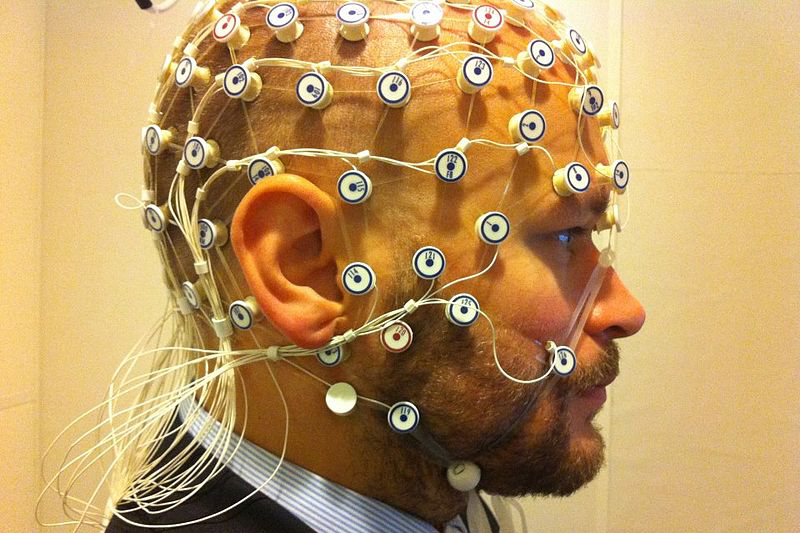

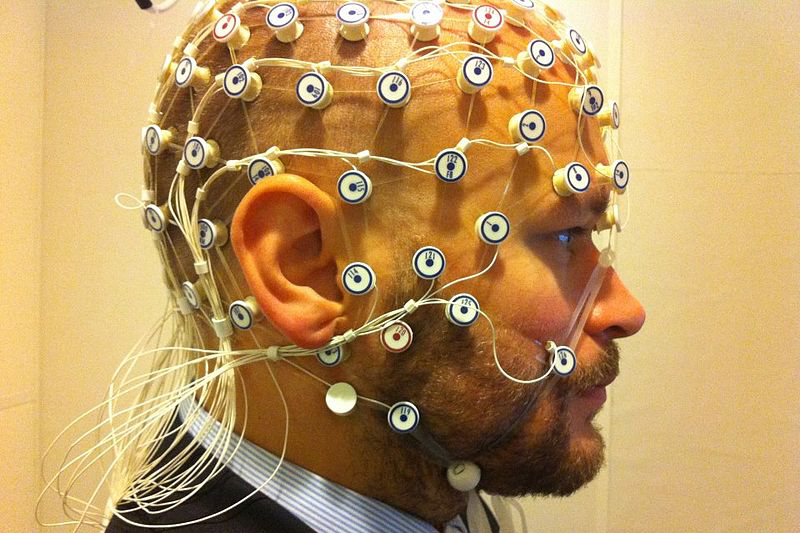

Scientists use electroencephalography (EEG) to measure electric activity in the brain during some kind of task in the lab (like looking at certain kinds of images). In the last couple years, neuromarketers have embraced cheap, user-friendly EEG systems that claim to work with dry sensors, removing the need to dab messy conductive gel on someone’s head. It’s more efficient than expensive, bulky MRI machines, but it comes with a price.

The messy, long process of applying electrodes to the scalp ensures the best quality data:

Modern research-grade EEG systems can use up to 256 separate electrodes, and fixing them to a subject’s head using conductive gel (in order to get the best possible connection) is a messy business that can take several hours.

The dry-contact systems with one sensor or a few can record only the most basic kind of data, and they do so with much lower fidelity and reliability.

And there’s often just not enough data, or sophisticated analysis, to ensure the reliability of the subsequent findings:

The signal-to-noise ratio in EEG data is poor, so sophisticated filtering and analysis techniques are required to pull out the weak signal from the background noise. Because of this poor signal-to-noise property, large numbers of repetitive trials are required in an experiment, and large numbers of subjects are also needed to demonstrate a reliable effect.

In general the same applies to getting information out of a data set as to getting information out of a human: If you torture it long enough, it’ll tell you everything you want to know, but information extracted under torture is highly unreliable. In addition, marketing-related studies are not well-suited to the kind of repetition that’s required to boost the useful signal and reduce noise; the same product or TV commercial can be presented only a few times before the participant becomes very bored indeed and therefore ceases to have any kind of meaningful reaction.

These technical issues could, in theory, be solved by changing the experimental design or upgrading the equipment, but Wall points out that there’s a larger issue with neuromarketing that will remain an impediment to getting any good scientific results: reverse inference.

Instead of carefully examining data between control and experimental conditions, neuromarketing studies often jump to conclusions about what a jump in something like an EEG signal mean about how the study subject is thinking or feeling.

An experimenter might observe a change in the EEG signal and infer that this means the participant is paying more attention. Unfortunately, logically this doesn’t work. Nothing has been systematically manipulated or tested, so this is not a safe assumption. The signal change might be because a participant just thought about his boyfriend, or experienced an itch on her foot, or felt hungry, or any number of other possible things. There is no unique brain signature of any particular cognitive or emotional state that can be seen with current technology. Labelling a set of brain data as a signal of attention or anxiety based on previous experimental findings is similar to saying “tomatoes are red, this apple is red, therefore this apple is a tomato.” It’s plainly nonsense.

Until more rigorous scientific standards come into play, it’s pretty hard to say what your brain really thinks about that ad campaign.

Read the whole piece here.