An old folk remedy involving hairy bean leaves strewn around the bedroom may have a new life as a modern bed bug trap, according to new research from the University of California, Irvine and the University of Kentucky. With insecticide resistance on the rise, such a device could be a helpful tool for treating bed bug infestations.

Although its mechanisms weren’t known at the time, the tactic dates back to at least 1678, when the English philosopher John Locke wrote of placing kidney bean leaves under the pillow or around the bed to keep bed bugs from biting as he traveled through Europe.

In the early twentieth century, the approach was also common throughout the Balkans, according to a 1927 report from the Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Army. That report suggested the leaves stunned the bloodsucking bugs as they traveled from hiding places to their sleeping hosts during the night; in the morning, the bug-covered leaves were removed and burned (dense infestations could allegedly amass over two pounds of the buggy leaves in a single room).

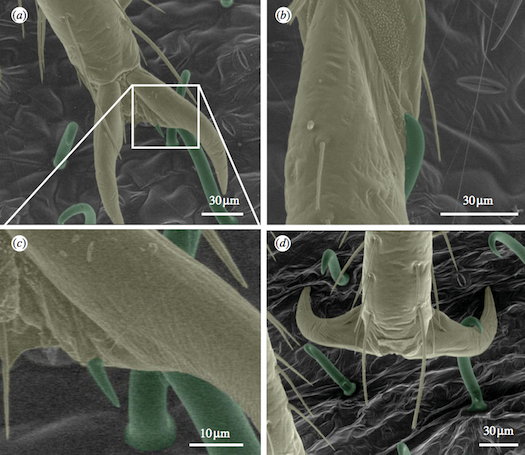

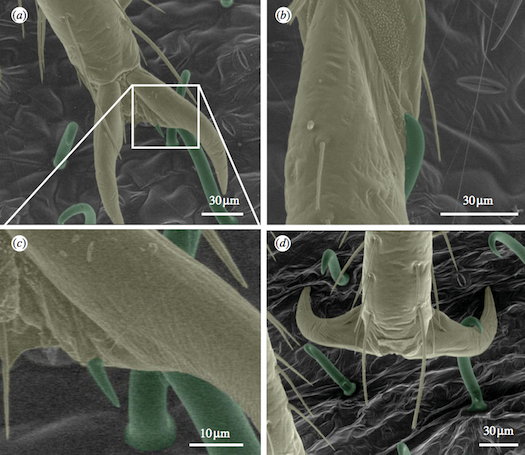

American entomologists studying the effect in the 1940s noted the bed bugs “could hardly be induced to move from the leaves,” and microscopic images suggested that fine, curved hairs called trichomes on the bottom of the leaves snagged the bugs’ feet.

Now, the California-Kentucky team has zoomed in even closer to reveal that the leaves’ sharp trichomes actually pierce the bugs’ feet like meat hooks, immobilizing them.

“It was astonishing to me that it worked at all,” says Catherine Loudon, a physical biologist at UC-Irvine and lead researcher of the new study, “You see this big muscular bug vigorously struggling, and it’s astonishing to me that the little tiny microscopic hairs don’t snap.”

Loudon’s team tipped single male bed bugs from a glass vial onto the bottom surface of kidney bean leaves, which usually captured the bugs within seconds (they used males, rather than a mix of both sexes, to avoid making baby bed bugs).

A low-vacuum scanning electron microscope (LV-SEM) allowed the researchers to examine the bugs while they were still trapped on the leaves. The images revealed that the trichosomes sometimes hooked the bugs’ feet like Velcro, but more often went right through. Some bugs were able to rip themselves free by breaking the trichome or rending their own flesh, but they were usually recaptured.

While there is no evolutionary connection between bed bugs and bean leaves, similar trichomes on other plants are known to capture ants, aphids, bees, flies, and leafhoppers, among other species. Scientists hypothesize that the structures first evolved for other reasons, possibly to retain water, with the defensive role coming later.

Of course, keeping fresh bean leaves on hand isn’t an easy bed bug fix, says Loudon: “The inconvenience of bean leaves is that not everyone wants them scattered around their bed room.” Synthetics mimicking the surface of the bean leaf, however, could be placed “as a ring around the bed legs, a floor mat at the door, a strip on the bed board, it could be something one put’s in one’s suitcase,” Loudon adds, since bed bugs “really only get from one place to another by walking or being carried.”

Ideally, a synthetic version would have the same geometry and physical properties as a real leaf, meaning the trichomes would be in the same locations and would move the same way as a bug walks through. To do this, Loudon and her team used dental impression putty to create negative molds from the surface of the real bean leaves, then filled these molds with epoxies of varying strengths and stiffnesses.

While the spacing of the trichome replicas matched the original leaves perfectly, none of the synthetic leaves worked as well as the real leaves, in part because the thin hooked ends of many of the trichomes broke off during the molding process. And, unlike the natural trichomes, which are hollow, the synthetic versions were solid, which meant they moved differently as the bugs walked through.

Loudon adds that the team is working on new synthetic versions that may address these issues, and has also optioned the technology to an undisclosed company.

Of course, a bed bug trap only works if a bed bug actually walks through it, which means it is unlikely that even a crafty biomimetic material will be a final solution for a bed bug infestation, but instead one part of an approach that may include heat, steam, vacuuming, and insecticides.

Brooke Borel is a contributing editor at Popular Science and is writing a book about bed bugs for the University of Chicago Press. Follow her on Twitter @brookeborel .