A set of 135 million-year-old fossils, once thought lost during World War II, are now accounted for and analyzed. According to a study published July 18 in the Journal of Systematic Paleontology, a team of international researchers from Germany and the UK has determined the “well preserved” skull and first neck vertebrae are from what they now call Enalioetes schroederi. But while paleontologists now know they belong to a newly discovered species of ancient marine crocodile, these creatures likely looked more like dolphins than reptiles.

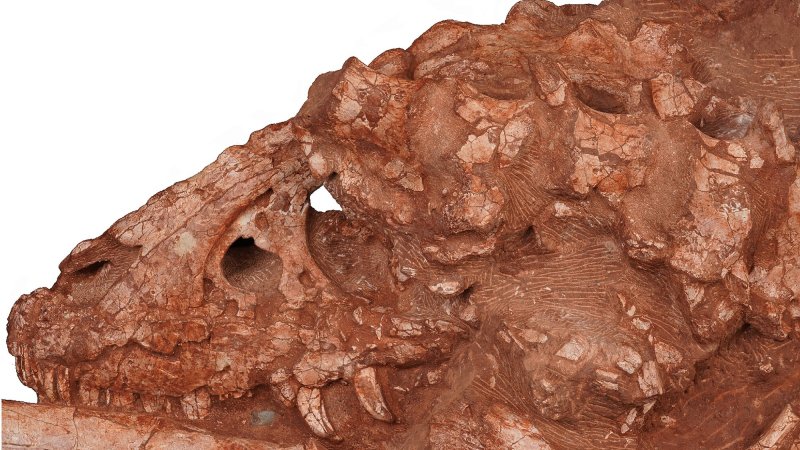

Between the Middle Jurassic to Early Cretaceous period, oceans were populated by multiple crocodyliform Metriorhynchidae species, a family known for their distinct body shapes and physical characteristics. Unlike today’s scaly and often bulky crocodiles, metriorhynchids featured flippers, a tailfin, and smooth, scaleless skin. Given their physiology more resembled modern dolphins than reptiles, metriorhynchids were likely speedy swimmers that fed on fast prey such as fish and squid. Some species also notably evolved large, serrated teeth, which paleontologists believe imply a diet that also included other marine reptiles.

[Related: Say hello to the surprising crocodile relative Benggwigwishingasuchus eremicarminis.]

Most metriorhynchids lived during the Jurassic period, but some, like E. schroederi, continued to evolve and exist into the Cretaceous. It wasn’t until recently, however, that researchers could confirm E. schroederi’s finer details due to a case of lost-and-found that stretches back over a century.

First discovered around 1916 by a German architect now known only as D. Hapke near Hannover, the skull and vertebrae were soon given to Henry Schroeder at Berlin’s Prussian Geological Survey. Experts initially believed the fossils belonged to an undetermined type of ichthyosaur, but eventually realized they were from a wholly separate creature.

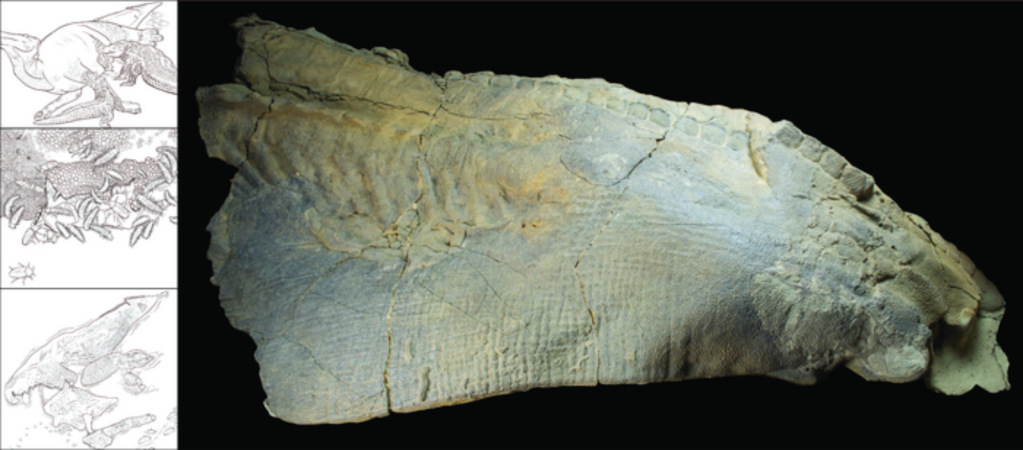

From there, however, details get murky. For decades, paleontologists believed the fossils were lost during Berlin’s destruction in World War II. Later, however, it was revealed Schroeder returned the specimens to their original finder, D. Hapke, whose family actually brought them to the Minden Museum in Western Germany, where they remained for years. Upon realizing this, a team from Naturkunde-Museum Bielefeld and the University of Edinburgh got to work on studying the rediscovered fossils, including subjecting the almost fully intact, three-dimensional skull to a CT scan.

“[W]e were able to learn a lot about the internal anatomy of these marine crocodiles. The remarkable preservation allowed us to reconstruct the internal cavities and even the inner ears of the animal,” Sven Sachs, project leader from the Naturkunde-Museum, said in an accompanying statement on August 9.

The new information shows how metriorhynchids evolved a “body-plan radically different from other crocodiles” during the Cretaceous Period. This included even larger eyes than their ancestors, which were already big by crocodylian standards, as well as more compact, bony inner ears. According to Mark Young, a study collaborator at the University of Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences, this latter fact is a sign that “Enalioetes was probably a faster swimmer” than their relatives.

While they determined the fossils belonged to an entirely new species, Sachs and Young chose E. schroederi’s name to honor the man who detailed the very first descriptions of the ancient creature before its decades’ long disappearance—and eventual resurfacing.