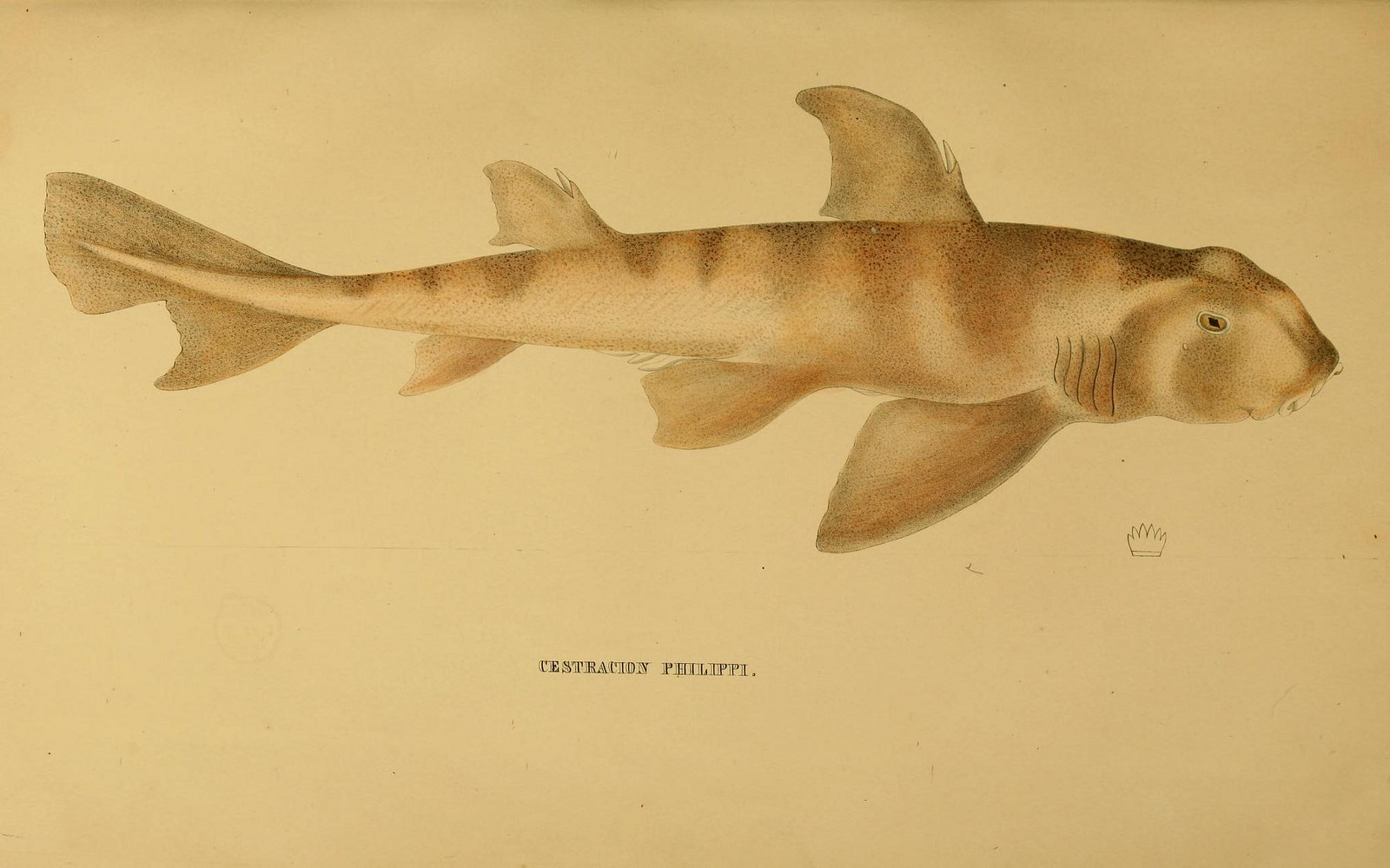

It’s a tale as old as time: Boy meets girl, boy and girl make babies, boy goes away, girl just keeps having babies, sperm-be-damned. While Leonie the zebra shark can’t quite claim a “virgin birth”—she had a couple dozen pups with a male partner in the early 2000s—scientists have confirmed that the three babies she made in 2016 were a total inside job. Without any genetic contributions from a male partner, Leonie got pregnant and had three healthy pups.

Parthenogenesis—asexual reproduction in a female—has been seen in other animals before, though it’s rare enough to cause a bit of a stir whenever it’s caught on the record. But scientists are especially excited about Leonie’s case: As researchers reported this week in Scientific Reports, she’s the first shark ever known to have switched from sexual reproduction to asexual. This duality shows that Leonie really did adapt to her circumstances—she wasn’t some fluke of an asexual being; she had pups the usual way but took matters into her own hands when males got scarce.

That’s a switch that scientists rarely get to observe, and one they don’t really understand very well: In one of the two other known cases, a female eagle ray switched from sexual reproduction to producing a pup asexually less than one year after being separated from her male partner—which seems like an awfully short grieving period. The other case was even stranger, with a female boa constrictor giving birth to parthenogenic pups after reproducing sexually and while there were males available for her to mate with.

But while the exact mechanism of this sexual switch is still mysterious, it’s clearly an ingenious evolutionary strategy—even if it’s only a short-term solution. After all, the extreme lack of genetic variety will make a population more vulnerable to dangerous mutations, and slower to adapt to new environmental circumstances. It’s also likely that Leonie’s solo offspring will be asexual reproducers themselves, which would limit their longterm usefulness in the gene pool. Being a literal single mother gets old after a generation or two, so male tiger sharks needn’t worry that they might become obsolete.

“It might be a holding-on mechanism,” study author Christine Dudgeon at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia told New Scientist. “Mum’s genes get passed down from female to female until there are males available to mate with.”

The zebra shark fossil record shows evidence of several population bottlenecks (sharp reductions in the population) associated with ice ages. Perhaps, Dudgeon and her colleagues write in the study, the ancestors of today’s zebra sharks were able to hold out longer than some of their cousins by squeezing out a few extra generations of female clones. Since zebra sharks are now listed as endangered, it’s heartening to see evidence that they might have a few tricks up their sleeves—even if scientists still don’t know how or when this astounding reproduction might occur.