Both vacationers and residents in Galveston, Texas, knew a storm was approaching on September 7, 1900. But there was no evacuation, and most everyone stayed put, not realizing the scale of the coming fury. The next day, surging waters killed 8,000 people.

This event remains the most lethal natural disaster in U.S. history. But with dramatically improved forecasting, it’s unlikely to happen again.

“You’re not going have a storm sneak up on Galveston,” says James Franklin, Branch Chief for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA) Hurricane Specialist Unit, who has flown into over 80 hurricanes on NOAA aircraft. “People will have notice and will be able to take action.”

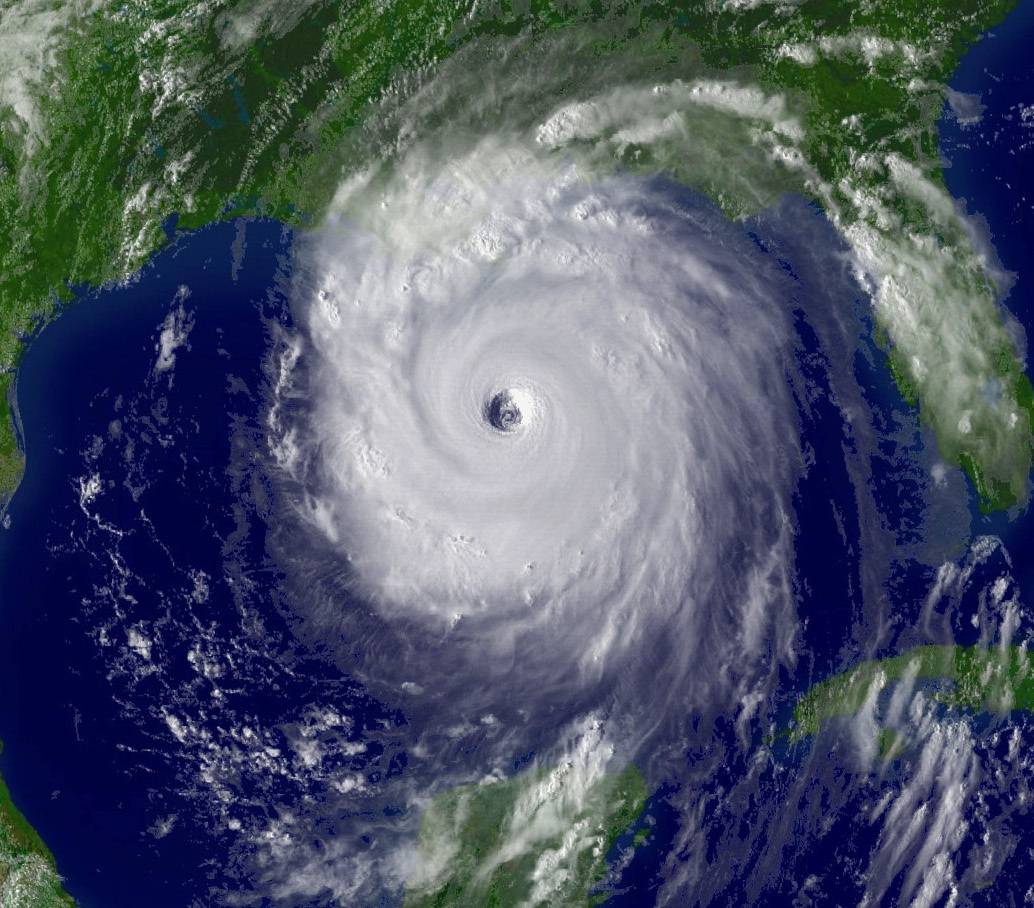

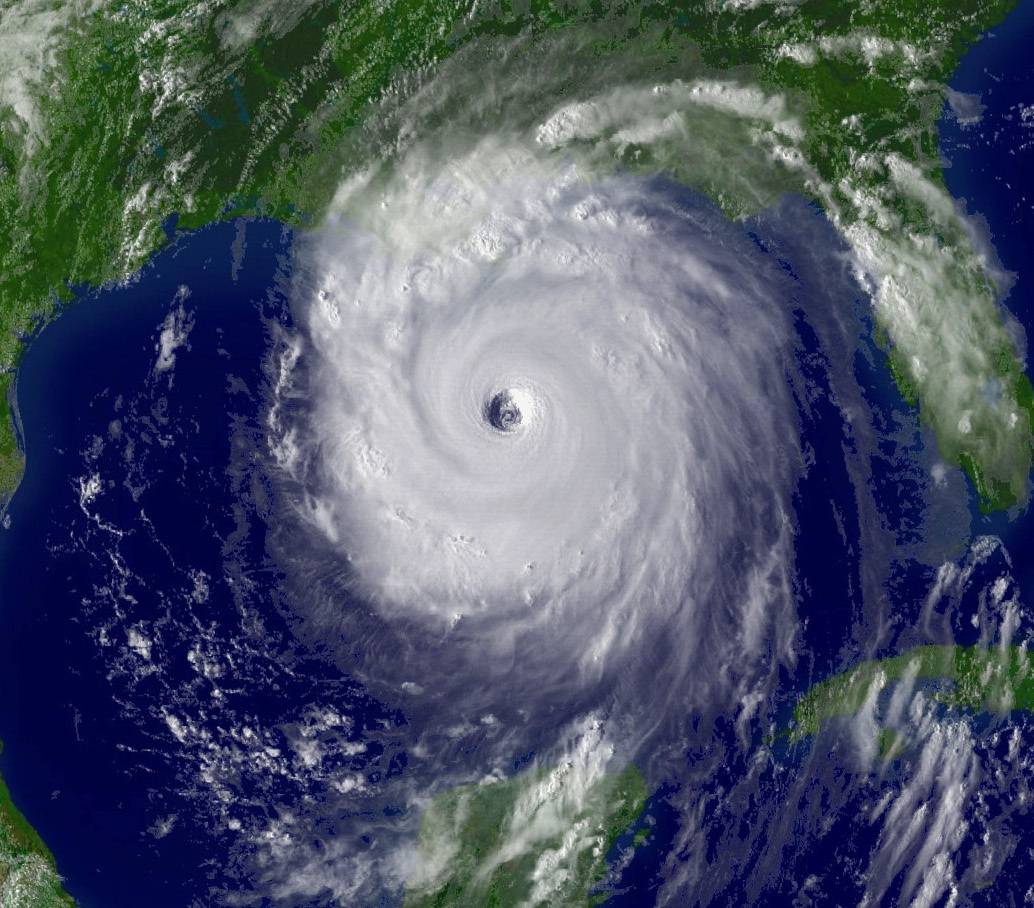

A crucial difference in modern storm forecasting is NOAAs fleet of sophisticated weather satellites. With such advanced storm-tracking systems, it might seem obvious to expect that hurricanes kill less Americans than they did decades ago, but “It’s not an easy number to estimate,” says Franklin. After all, hurricanes are still deadly, and every storm is different. But evidence does exist. In a 2007 study published in Natural Hazards Review, scientists demonstrated that improved storm forecasting prevented up to 90 percent of deaths that would have occurred should satellite-less, error-prone technology still have been used used to predict hurricanes.

The researchers found that between 1970 and 2004, an average of around 20 people died from hurricanes each year. But if forecasts were as faulty as they were in the 1950s, they estimated that 200 people would have died each year, simply because significantly more people had settled into the path of destructive cyclones.

“The bottom line is that the number of deaths have been going down, but the coastal population has been going up,” says Hugh Willoughby, the study’s lead author and a hurricane researcher at Florida International University.

With better predictions, these vulnerable, swelling populations have more time to flee than they did 50 years ago. “What was really happening before 1970 is that every few years there was storm that would kill a few hundred people—sometimes more and sometimes less,” says Willoughby. “Since 1970 we’ve done a really good job of reducing those events.”

These might be useful numbers for the nation’s lawmakers to consider. For all of NOAA’s vigilant storm-tracking efforts, a four-page white house budget memo obtained by The Washington Post last month revealed significant proposed cuts to NOAA, including $513 million to its satellite data division. But in encouraging news for the millions of Americans that live in cyclone-territory, on March 30 the U.S. Senate passed the Weather Research and Forecasting Innovation Act of 2017, which as its name suggests, supports hurricane science. Next, the bill will be considered by the House of Representatives.

Following World War II, the U.S. still used pretty simple forecasting tools. Airplanes took rough rides into these tempests, found the storm’s center, and then returned every six hours to find the center once again. In 1960 the United States’ first weather satellite, TIROS-1, took orbit, giving forecasters their first glimpse of menacing clouds moving across the ocean. By the 1970s, satellite images began appearing on people’s televisions, “which made it a lot more real,” says Willoughby.

But it’s been in the last couple decades that forecasting has significantly improved, and advanced satellites are the difference, although sophisticated computing has also played an important role.

“You need a good starting point, and that’s where satellites come into play,” says NOAA’s Franklin. “Over last 25 years they’ve been providing more quality and quantity, especially over oceans where it’s difficult to get measurements.”

Although predicting where tumultuous weather might go is challenging, NOAA’s errors in storm tracking have been cut in half in the last 12 to 15 years, explains Franklin. And beginning five years ago, the agency could give imperiled residents 12 more hours of notice that a hurricane was expected to hit (we now get 36 hours of advanced noticed—up from 24 hours).

Our ability to predict the intensity of storms, however, has not kept up with the forecasting of where these storms might land.

”Intensity is a different problem, and a harder problem,” says Franklin. “You need much more detail.” The factors that influence a storm’s intensity happen on a much smaller scale than the big atmospheric features that push giant storms around.

The agency is working to understand these details. “Saving lives also involves getting the intensity right,” says Franklin. “If you’re trying to make a decision about how many people to evacuate, you need to know if it’s a strong storm.”

Fortunately, a promising solution exists, and it’s called the Hurricane Forecast Improvement Program. “It’s the most focused effort to improve guidance that hurricane forecasters have,” says Franklin. Its funding, which supports both NOAA scientists and high-level computing, was once around $14 million annually.

“That’s a huge amount in the hurricane world,” says Franklin. But the budget has been slashed to around $3 million, “meaning we won’t sustain progress for intensity, and that’s a concern,” he says.

Even without accurate intensity forecasting, tracking where the storms will land has proven invaluable to the public. Hurricane Katrina killed approximately 1,200 people, but it could have been dramatically worse. “If it hadn’t been for 60 hours of forecasts we would have been looking at 10,000 or 20,000 killed,” says Florida International University’s Willoughby. “To the credit of the people in New Orleans, they did what they should have done. Only 15 percent were there when the storm hit. That’s a phenomenal response to an evacuation order.”

No amount of storm forecasting, however, will prevent major property damage. People can flee, but the buildings stay.

“It’s easy to get a 10 billion dollar hit,” says Willoughby. “Expect that every few years.”

Rising seas, which facilitate flooding, make property damage more likely. Willoughby points at Hurricane Sandy, a flooding event that caused nearly $70 billion in damage.

Aside from billions of dollars in destruction, rising seas imperil lives. “The thing we have to worry about is rising water. That’s gonna be our big threat,” he says. “There’s no question that moving water kills most of the people in a hurricane.”

This was certainly the case 117 years ago in Galveston. Since then, sea levels have risen by about eight inches, and the effect continues.

Sea level rise is driven by warming oceans, which cause the water to expand, and melting ice, notably from glaciers, which are receding globally. Should enough glacial ice melt, sea levels could rise by as much as three feet—or more—by the end of the century.

“Glaciologists run around with their hair on fire, and they may be right,” says Willoughby.