Why can newts and toads regrow limbs, but we can’t? New genetic research might hold the answer to this evolutionary question.

By manipulating the genes of African clawed frog tadpoles, a group of researchers has found that the ability to regenerate limbs, a trait possessed by many cold-blooded animals, is based on whether or not an animal carries one particular gene. The results of their study are out this week in the journal Cell Reports.

The team named this gene c-Answer (short for cold-blooded animals specific wound epithelium receptor-like). They think that warm-blooded animals lost this gene when they evolved from being cold-blooded to warm-blooded. The gene’s disappearance in warm-blooded animals seems to have caused changes in appearance related to head size, changes in brain size, and the loss of the ability to regenerate at the level cold-blooded animals can, says organic chemist Daria Korotkova of the Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, and the main author on the study.

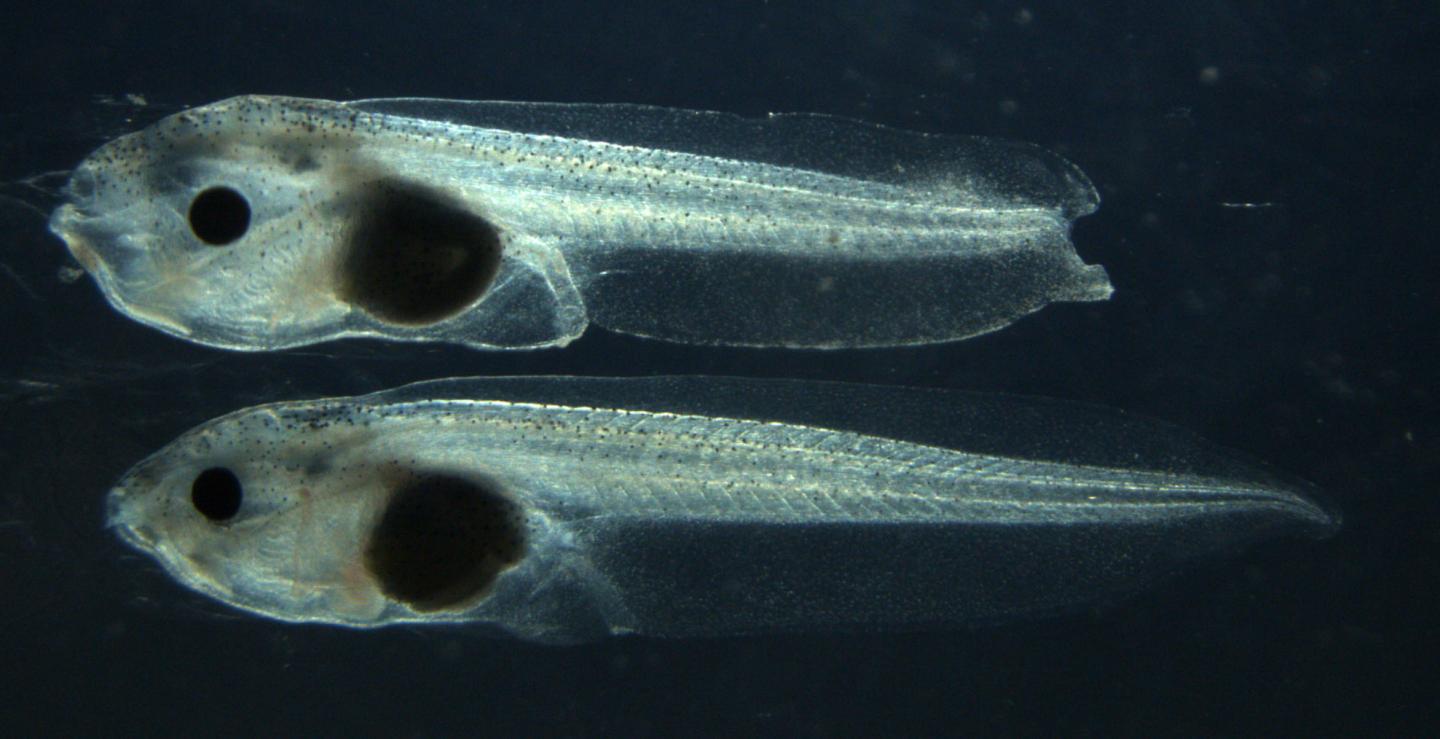

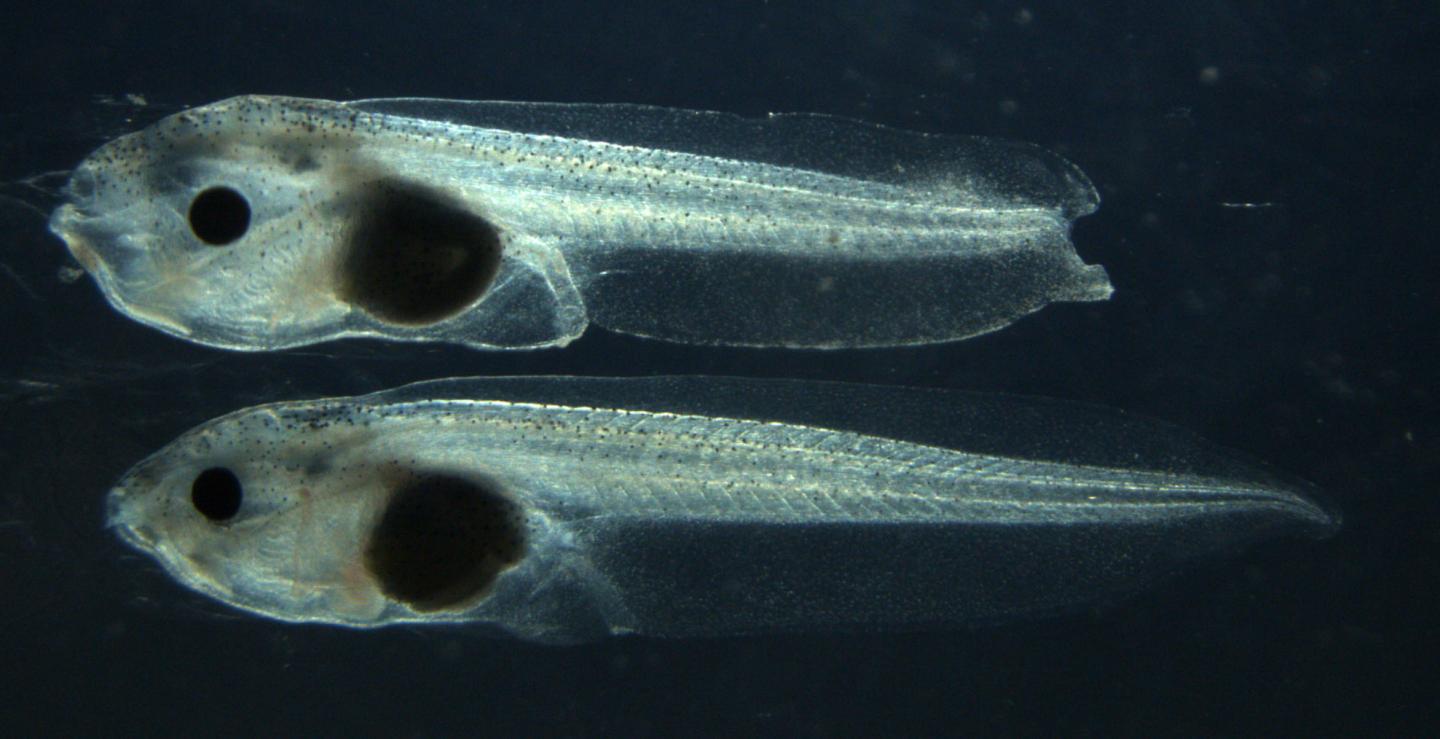

To do the research, she and her co-authors turned off or enhanced the function of the c-Answer gene in two groups of tadpoles, and looked at what happened when they did so. With the gene enhanced, the tadpoles had more brain growth and larger eyes than regular tadpoles, and, of course, they could still regenerate their limbs, even during a period of development called the “refractory period” when they normally cannot regenerate. When the gene was turned off, however, the tadpoles could no longer regenerate their limbs at all, and had smaller brains.

Finding c-Answer wasn’t dumb luck: Korotkova and her team used a computer algorithm to figure out which genes code for regeneration in the genomes of a number of fish, amphibians, and reptiles. Then they looked for similar chunks of DNA in warm-blooded species like the platypus, Tasmanian devil, human, mouse, and guinea pig. Finally, they selected one of the genes missing from the warm-blooded animals that encodes for a protein related to healing, and used the gene-editing technique CRISPR to enhance or delete the genes in tadpoles.

Warm-blooded animals—birds and mammals—don’t have the c-Answer gene at all. This might explain why we can’t just regrow a limb at will like our cold-blooded distant cousins. The researchers also think some of the other genes we lost when we evolved into warm-blooded animals are also related to regeneration.

But what exactly this all means in terms of the history of evolution is still being understood. “It was unexpected that the disappearance of one gene could cause such dramatic changes in the function of the body,” Korotkova says. Next, she says, she and her colleagues want to study the gene and the proteins it codes for in more depth, and also further examine what it does to the brain.

While the work doesn’t have any direct bearing on human health today, the search method might help other researchers better understand human evolution. “We have developed an algorithm and a computer program for a systematic search for genes lost at a certain step of evolution,” the researchers write. The discovery of c-Answer shows this method can work. Now it’s just a matter of using it to further peer into our evolutionary history.