Sometimes, a name just sticks with you. When 17th century astronomers peered up at the dark spots on the moon, they thought they looked like vast lunar oceans. We still call these spots maria (Latin for ‘seas’), even though Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s landing in the Sea of Tranquility was less of a splashdown and more of a gentle plunk onto some hard rock.

But just because those seas seem bone-dry, that doesn’t mean that all areas of the moon are water-less. Analysis of fragments of volcanic glass brought back on later Apollo missions showed that tiny droplets of water were embedded in the material. Now, a study published Monday in Nature Geoscience shows that the moon might hold even more water than previously thought.

Before you start packing your lunar swimwear, let’s hear from one of the lead authors of the paper, Ralph Milliken. “We’re not talking about liquid water. There’s no evidence for oceans or seas or rivers on the surface” he says. But that doesn’t mean that these small, scattered bits of water couldn’t eventually be tapped for human use.

Billions of years ago, Milliken says, huge fire fountains of lava erupted on the lunar surface, bringing up magma from the interior of the moon. That magma contained something geologists call volatiles—substances like carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, hydroxyl, and water—which at great depths (like, inside the moon) stay dissolved in melted rock. But as the magma moves up towards the surface, those volatiles can separate out into swiftly-expanding gasses, just like bubbles in a recently uncapped bottle of soda.

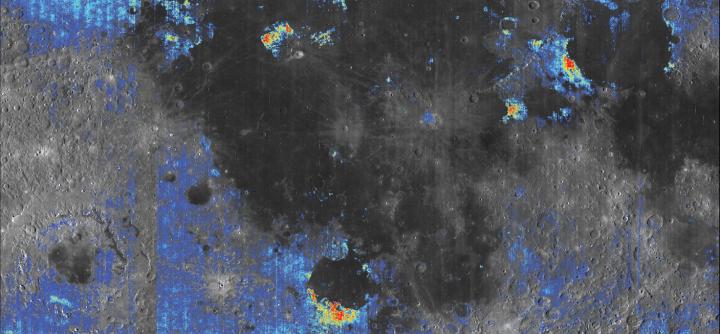

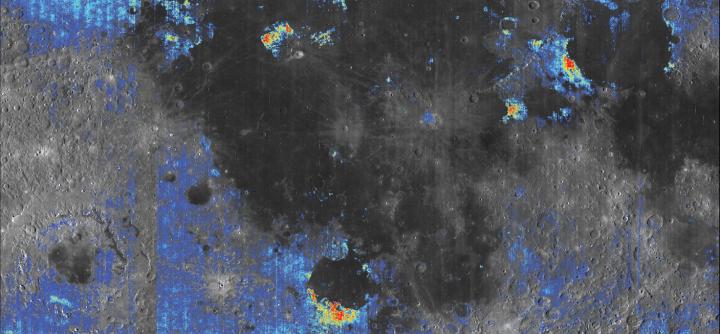

As the lava exploded out onto the surface, it cooled fast. So fast, in fact, that some of those volatiles got trapped in volcanic glass beads. That’s the water that Milliken and his colleague, Shuai Li—now a post-doc at the University of Hawaii—were able to detect on the moon’s surface using a relatively new technique that measures the amount of water in rocks by analyzing reflected sunlight bouncing off the lunar surface.

“It’s not much [water], maybe a couple hundreds parts per million, but the size of these deposits are huge, you have a lot of material to work with,” Milliken says. “Theoretically, we could extract water from these deposits for human exploration.”

Extracting the water wouldn’t be as simple as drilling a well here on Earth. The material, Milliken says, would likely have to be mined from the deposit, then heated to release the water from its glassy prison. After that, you’d have to condense the water back into a usable, liquid form. There’s likely enough material on the moon to make that process possible, but before we start mining moon rocks for water, we need more information from the moon itself.

Li and Milliken used remote sensing to draw their conclusions about the amount of water on and beneath the moon’s surface, but it would be even better to have additional samples gathered by future crewed or robotic missions. The samples we have from the Apollo missions were taken from the very edge of these water-rich formations. More samples, taken from places that may have even more water, could help validate and constrain these initial results.

Of course, there are other sources of water on the moon. There is actual water ice in shadows, in the lunar dust, and at the moon’s poles, which researchers like Li and Milliken are working to characterize in order to make a tally of all the wet stuff in and on our rocky satellite.

“Other studies have suggested the presence of water ice in shadowed regions at the lunar poles, but the pyroclastic deposits are at locations that may be easier to access,” Li said in a statement. “Anything that helps save future lunar explorers from having to bring lots of water from home is a big step forward, and our results suggest a new alternative.”