Saturday will mark the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 landing on the moon, which was the first time in history humans set foot on an extraterrestrial world. But Earth’s only natural satellite is still a very unfamiliar place to us half a century later, and its history and geology are still puzzling—largely because we haven’t been back since 1972.

All of that is poised to change in the next decade as NASA and its partners ramp up new efforts to return, with an eye on staying permanently this time. With new ways of collecting data and new methods for analyzing it, some of our long-standing questions might soon have answers. Here are six of the biggest scientific mysteries about the moon still waiting to be cracked.

The Origin of the moon

“The fundamental question of how the moon formed, and how that relates to the Earth, is really the most important of the unknowns.” says Noah Petro, a research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and a project scientist for the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. “Everything else comes after that.”

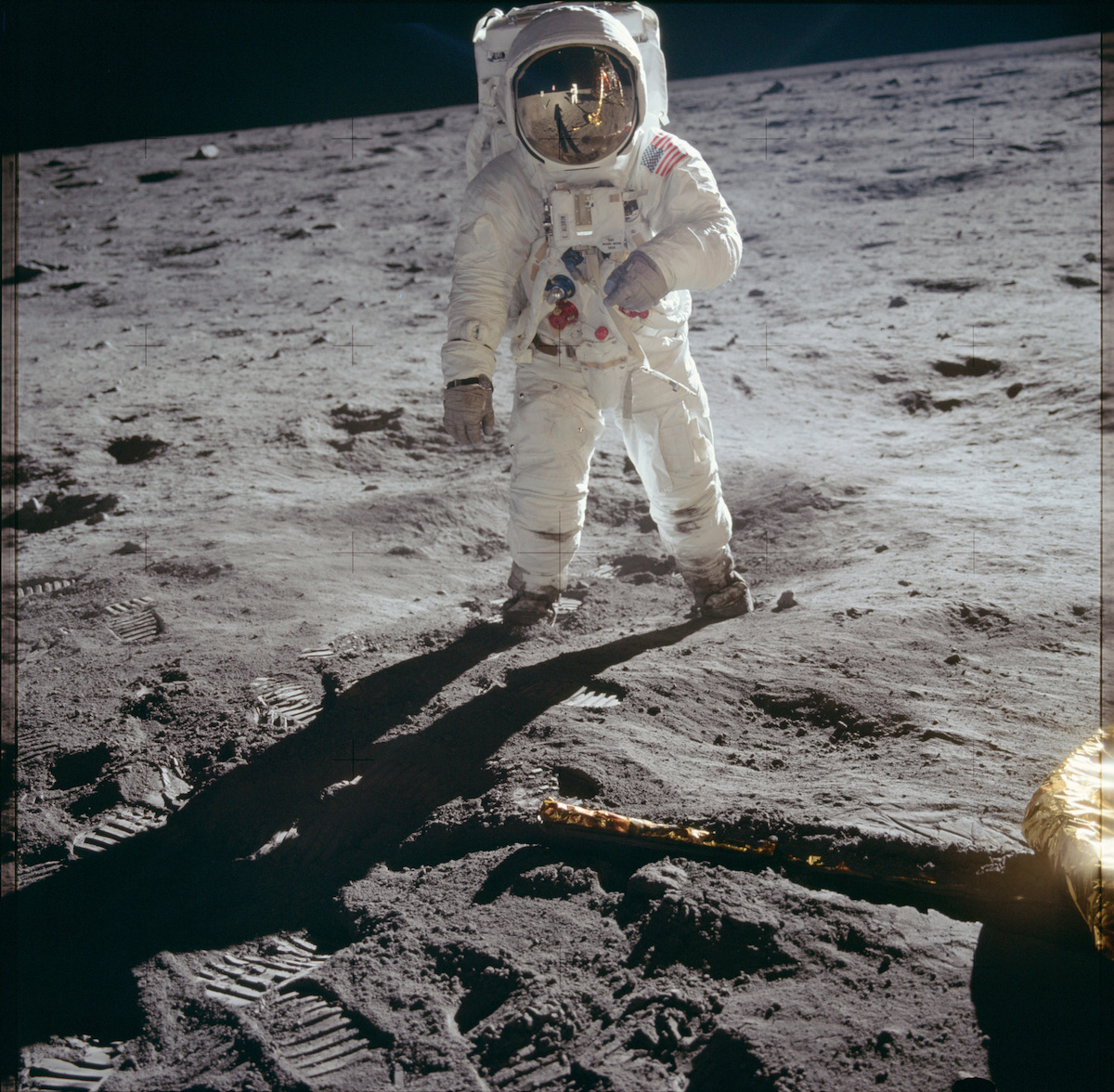

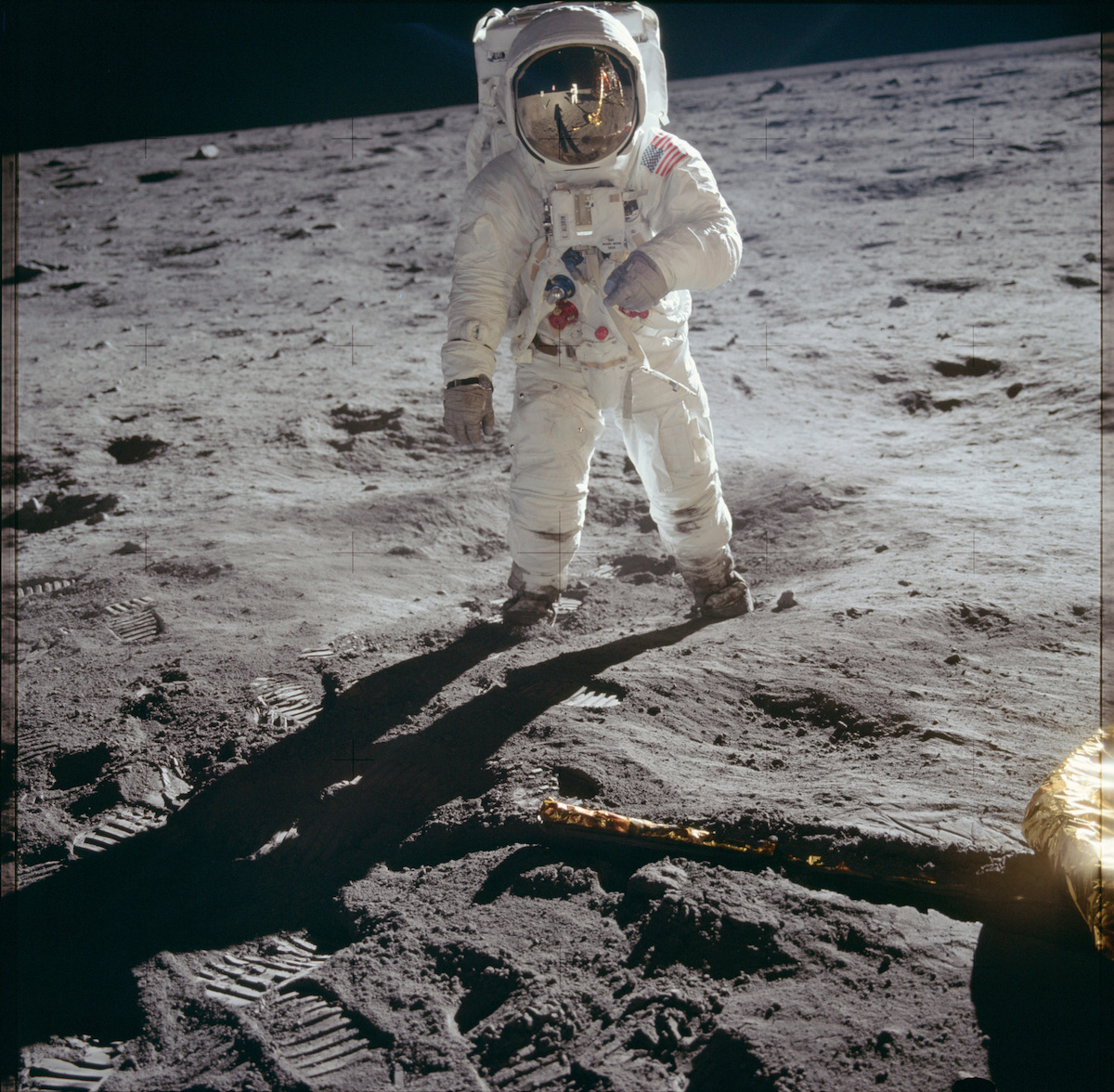

You can thank Apollo 11 for giving us our first insight into that mystery. The mission brought back 50 pounds worth of moon rocks and initiated decades’ of investigations focused on learning how the moon formed and evolved. “I can’t understate the importance of getting those first samples back from Apollo 11,” says Petro. “They set the stage for our entire understanding of the moon.”

Scientists used them to come up with the strongest existing model: that the moon began as a magma ocean—a giant ball of molten lava—orbiting Earth. This in turn led, decades later, to the hypothesis that the moon was borne out of Earth itself, when a giant impact with a Mars-sized object ejected debris into orbit. Further studies of the rock show the material that formed the moon also formed our own planet, adding more support to this idea.

That’s the most widely accepted hypothesis for the origin of the moon, but it’s by no means perfect. There is no way yet to confirm a giant impact created the moon, and our sense of how the magma ocean cooled down into the dry, gray rock we see now is still very hazy. About 10 years ago, we discovered evidence of water on the moon—something that’s a bit difficult to reconcile with an impact hypothesis. Getting to the bottom of the moon’s past requires the sort of on-the-ground work we’ve done to unravel Earth’s own history.

Water on the Moon

There’s water on the moon, and we’re not just talking about a little sprinkling of interstellar H2O—we’re talking about troves and troves of water-ice that could be sitting just beneath the surface, especially at the lunar poles. This water could be harvested to help generate a new form of spacecraft fuel or used to help sustain a future lunar colony.

How did all that water-ice get there? Nobody really knows yet. Theories range from outgassing reactions that pushed water embedded in the interior out toward the surface, to meteorite impacts and cometary bombardments that delivered the water from outer space, to chemical interactions catalyzed by solar wind. “We just don’t know,” says Petro. “And we’d certainly like to find out.”

Moonquakes

There are earthquakes happening on the moon pretty frequently—otherwise known as moonquakes. Apollo-era seismometers installed on the surface measured these shakes from 1969 to 1977. That data has shown us that the moon is an active body, a far cry from the stale lifeless rock many assume it is.

We’re already aware of a few phenomena that cause these quakes, like thermal expansion, tidal stress induced by Earth’s gravity, and meteorite impacts. But with such limited data, we’re not entirely sure how these processes work and exactly how the quakes behave. Moreover, there are other, shallower moonquakes without any obvious cause, which seem to be occurring more recently than the others. Petro suggests a global seismic network installed around the moon would be tremendously helpful in helping understand the trigger mechanisms behind all this tectonic activity. Such a network could cleanly identify exactly when these events occurred, where they originated from, and the effect they have on the rest of the moon. The 50-year-old data we’re using now won’t be enough to give us any good answers.

Tidal Locking

There’s a reason we’ve only ever seen one side of the moon. It’s tidally locked, which means only one side of it faces Earth. This is not uncommon for moons in our solar system, but it’s still unclear exactly when this occurs, what conditions encourage it, and how it happens. In Petro’s mind, this mystery of tidal locking harkens back to the question of the origin of the moon, and what was happening in early lunar history. It’s another piece of the 4-billion-year puzzle.

This mystery isn’t just local to the moon, either. As we continue to find more planets and moons outside of our solar system, it’s important to figure out what sort of factors help incite features like tidal locking, and decide whether potentially habitable worlds, like the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets, really are hospitable to life.

South Pole-Aitken Basin Anomaly

One enigma that’s sprung up only recently has to do with the discovery that something massive is lurking underneath the south pole of the moon, below the largest impact crater ever made in the entire solar system. Scientists have no idea what it could be, but it’s certainly big enough to affect the gravitational force exerted by the moon’s mass.

Predominant theories suggest it’s some sort of heavy metal body from a projectile that impacted the surface a long time ago, but this is far from certain. And it’s hard to understand what this mass is doing suspended underground: We know the moon’s interior is still active to some degree (e.g. moonquakes), and heat should have caused this mass to shift around instead of staying trapped like Han Solo in carbonite.

“It raises questions we’re just not able to answer yet,” says Petro. “I’ve been working for a number of years to try to get a mission together to study and sample the Aitken Basin, to study it directly. Just knowing its age would be a great place to start.”

Volcanoes on the Moon

We don’t see volcanoes erupting on the moon these days. But research suggests lunar volcanoes were active within the last 100 million years, and on the scale of the cosmos, that may as well have been last week. The problem is, we just don’t know enough about volcanism on the moon to determine what this activity was actually like and what it did to the moon’s geology. Different lunar rocks and observations based on orbiter imaging give weight to various attempts to explain this history. Some surfaces seem younger than others, and we’re not sure why. It all comes down to a need for fresh lunar samples.

The implications stretch beyond just learning more about the moon. Petro suggests that if we’re able to assess exactly how young a surface on the moon really is, we can use that knowledge to make predictions of how old the surfaces on other celestial bodies are, from Mercury to MU69. In turn, this could give us a better understanding of the solar system’s history. The moon is really just a small step toward the giant leap of unraveling the origin of everything we know.