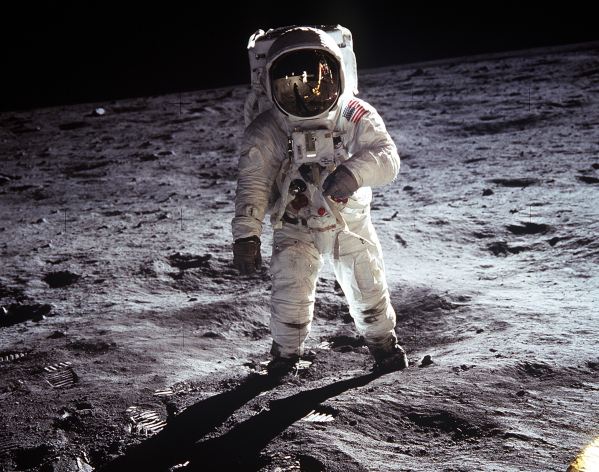

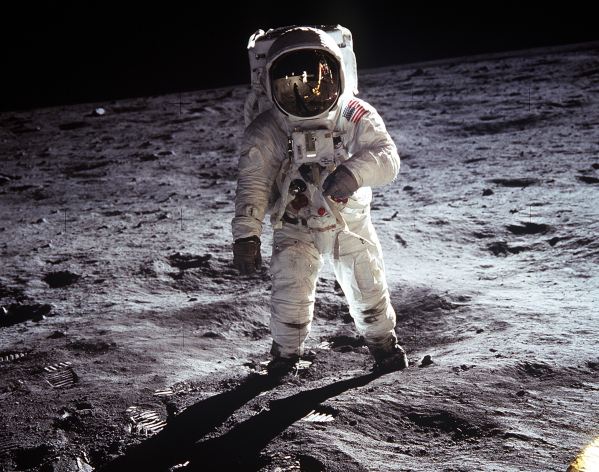

It’s been 40 years since Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin landed the Apollo 11 lunar module in the Sea of Tranquility. Aldrin, now 79 years old, recalls that fateful day with clarity. Alarms were sounding inside the space capsule during their speedy descent, and even down to the last seconds, the astronauts were uncertain whether they would need to abort the landing. Millions of Earthlings watched on television as the Eagle touched down.

Much has changed over four decades, and despite the success of the International Space Station, enhanced shuttle technology, robotic rovers, and satellites which bring us back daily analytical data from our solar system, the visionary optimism that once propelled the space race and captured the world’s collective imagination has waned. Ironically, with the loss of this optimism, the very notion of manned space travel beyond our moon seems to have become antiquated itself.

Dr. Aldrin, in the media blitz surrounding the moon landing’s historic anniversary and the release of his new memoir Magnificent Desolation, has been at the forefront, vocalizing his opinions and concerns about NASA’s space ambitions. A former Air Force pilot and MIT academic who made his reputation in the early days of the space race as a practical theorist and intrepid space walker, Aldrin has been a fierce advocate for continued manned expeditions into the space since retiring from NASA.

His personal experience on the moon (“Not a very pleasant place to set up housekeeping,” he notes) has led him to oppose NASA’s proposed return to the moon in 2020.

PopSci sat down with Dr. Aldrin for a chat about the possibilities for the future of space exploration.

Growing up during the 1930s and 1940s, was there a general fascination with space exploration?

No, only in comic book form, in science fiction. The writers back then made an attempt to be as realistic as possible and not to introduce anything that was clearly unrealistic or fanciful. Today, in order to be more bizarre or spectacular, people really deviate from the facts. And as a result, there’s projected unrealistic objectives, and the intimation that we ought to have miraculous breakthroughs around the corner.

And the focus of the science fiction was on Mars and Venus at the time and not on the moon?

Well, there were also periodicals: Destination Moon and such. It was certainly realized that it would be a challenge in itself, just getting to the moon. The more sage people recognized, in a bizarre observation, that if earth humans were meant to move into space, then God would have given us a moon — like he did. If we didn’t have that, the enormous task of trying to go to another planet would have been very, very daunting. And now that we’ve gone to the moon, we can go elsewhere.

What were your first impressions of the moon on that historic day?

We were approaching something that had never been done before, to slow down from an orbital condition. If the engine quit, you were going to crash, because there was no wind or atmosphere, so we were very careful. There wasn’t much to see once we’d landed… shades of grey, boulders, black velvet skies with no stars, which wasn’t a surprise, really, but the degree of serenity to it was a little outside of expectation.

What is the vision behind your advocacy for continued space exploration?

Well, it’s to chart a course of a longer-term, stepping-stone approach, that provides the U.S. with the preservation of the leadership attained by our investments in the ’60s and ’70s. And maybe we haven’t quite retained that leadership, even though the shuttle is a marvelous thing and the station is a collection of cooperative efforts.

I know that NASA has set a date for 2020 for a second manned mission to the moon and 2037 for a manned mission to Mars. Do you think these goals are reasonable?

I note that there’s an opportunity [for travel to Mars] in 2029 — an opposition — and in 2031. If we got to the moon in 2020, we couldn’t get to Mars. So I don’t think we can do both the Moon and Mars and get to Mars at all.

So you think we should focus on Mars?

Yes, I think we should help the internationals do that, to our benefit and to their benefit. For them just to ride on our coattails again, or try and compete with us, is a no-win situation for everyone.

Why would travel to Mars be more important than establishing space stations on, say, the moon? Is it simply for the sake of new exploration, or because Mars has an atmosphere with the possibility of terraforming?

Terraforming is very long-term — that’s pretty iffy — but it’s a survival question. Sooner or later, I think a mature society owes it to the future to preserve this society by establishing a survivable place other than Earth. There’s potential of life being there. When we get there, there will be life. We’ll start growing things and Mars will be gradually supportive of human existence. To just turn around and leave it would be a disservice to the investment we’ve made in going there. You can’t send just enough people for survival: you need to accumulate people. ■

The way to achieve this, Aldrin elaborates, is to take a new approach to space travel, and possibly revisit ideas from shuttle technology. He’s even outlined plans for a Aldrin Mars Cycler, a spacecraft that could be placed in a perpetual slingshot cycle around the Earth and Mars. This way, space shuttles could hitch a ride on the Cycler craft outside Earth’s orbit, and disengage once it reached Mars. If perfected, the transit between Earth and Mars could be shortened, perhaps to as little as six months for each leg of the journey. This, of course, would only be a mature strategy for the transit between the two planets once manned expeditions to Mars have proven fruitful. The first step would be one of commitment, by the U.S. and international community, to a long-term vision for Mars.

Whether or not NASA will heed Dr. Aldrin’s advice about its moon/Mars ambitions, or whether such a commitment to the fabled red planet would be of interest to the international community, has yet to been seen. The Obama administration has requested a full review of NASA’s current programs by the end of August. Perhaps then we will see if the U.S. can once again act on visionary ideas, so that further space exploration doesn’t fade back into the realm of science fiction once again.