The past is like a piece of Swiss cheese. You may get a sense of its two-dimensional rhombus proportions, its creamy yellow coloring, or its waxy texture, but the holes are still numerous. In linguistics, such a chasm is called a “lacuna,” like a missing chapter in an ancient text, or a word that should exist but doesn’t. In paleontology, it’s simply called a gap in the fossil record—and it’s an opportunity for a new discovery.

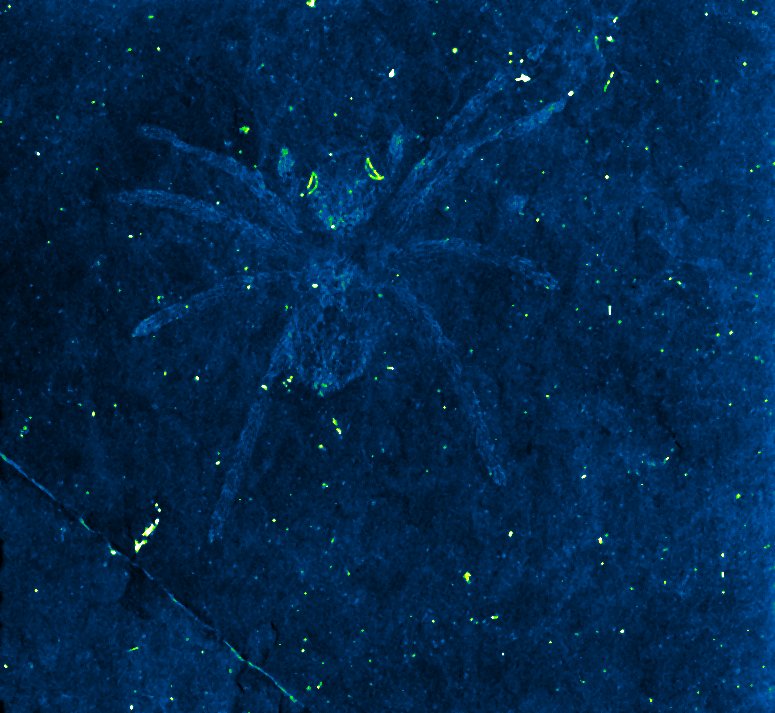

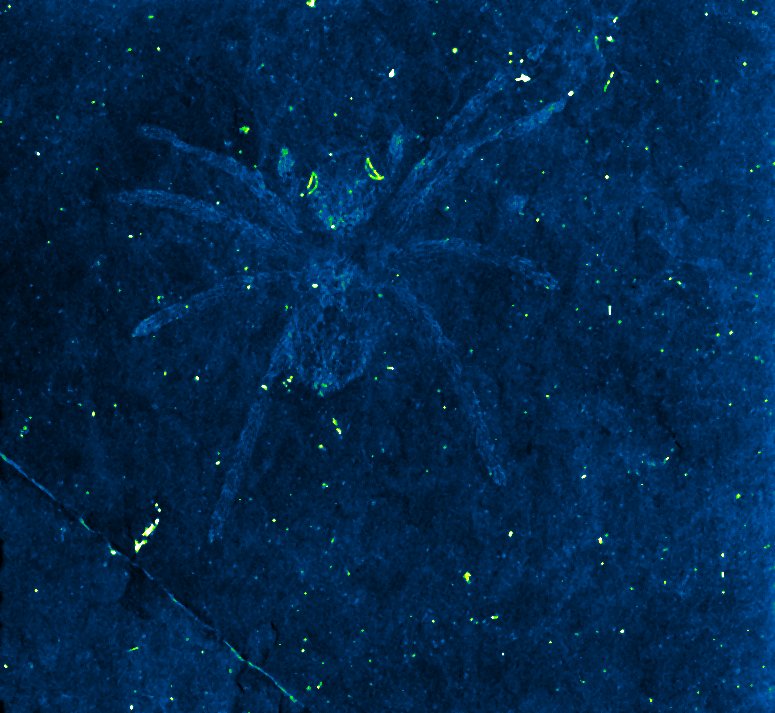

Paul Selden peered into one such abyss and found two sets of glowing eyes looking back at him. A geologist at the University of Kansas, he and his colleagues studied spider fossils in the spookily-named Lower Cretaceous Jinju Formation. The delicate eight-legged arthropods are typically preserved only in amber, but in this particular seam of Korean shale, several specimens of the extinct Lagonomegopidae family were trapped and, over eons, transformed into rock.

That spiders were fossilized in this way was not the only novelty reported in Selden’s recent paper in the journal Journal of Systematic Paleontology. Two of the 110 million-year-old specimens also had glowing eyes.

Tapetum lucidum, a light-reflecting tissue layer, is not uncommon in the animal kingdom. The surface, which gets its name from the Latin word for bright tapestry or coverlet, is common in animals ranging from cats to raccoons. It’s why photos of your dog often come back with an alien glare. The feature is even seen in some modern spiders, like wolf spiders that hunt at night. (“If you walk around a field at night with a headlamp you will see many tiny spots of light which are lycosid eyes reflecting the headlamp,” Selden wrote via email.) But this study is the first to describe the tapetum of a fossilized arachnid.

“This tapetum was canoe-shaped—it looks a bit like a Canadian canoe,” Selden said in a press release. It coated the spider’s posterior median eyes, which sit at the very top of its head. And it had maintained its iridescence through the ages. Though the bodies of some of the spiders may look flat and faded like cave paintings, these eyes leap off the .jpg.

While the discovery was noteworthy in and of itself, the authors think the specimens could provide even more insights down the line. For one, it may be worth reconsidering plentiful amber specimens, which could have preserved spider fossils with similar eye features but masked their reflectivity. It also highlights some of the lingering gaps in our understanding of spider evolution. “This is an extinct family of spiders that were clearly very common in the Cretaceous and were occupying niches now occupied by jumping spiders that didn’t evolve until later,” Selden said in a press release. “But these spiders were doing things differently. Their eye structure is different from jumping spiders.” Exactly how and why these changes occurred has yet to be illuminated.