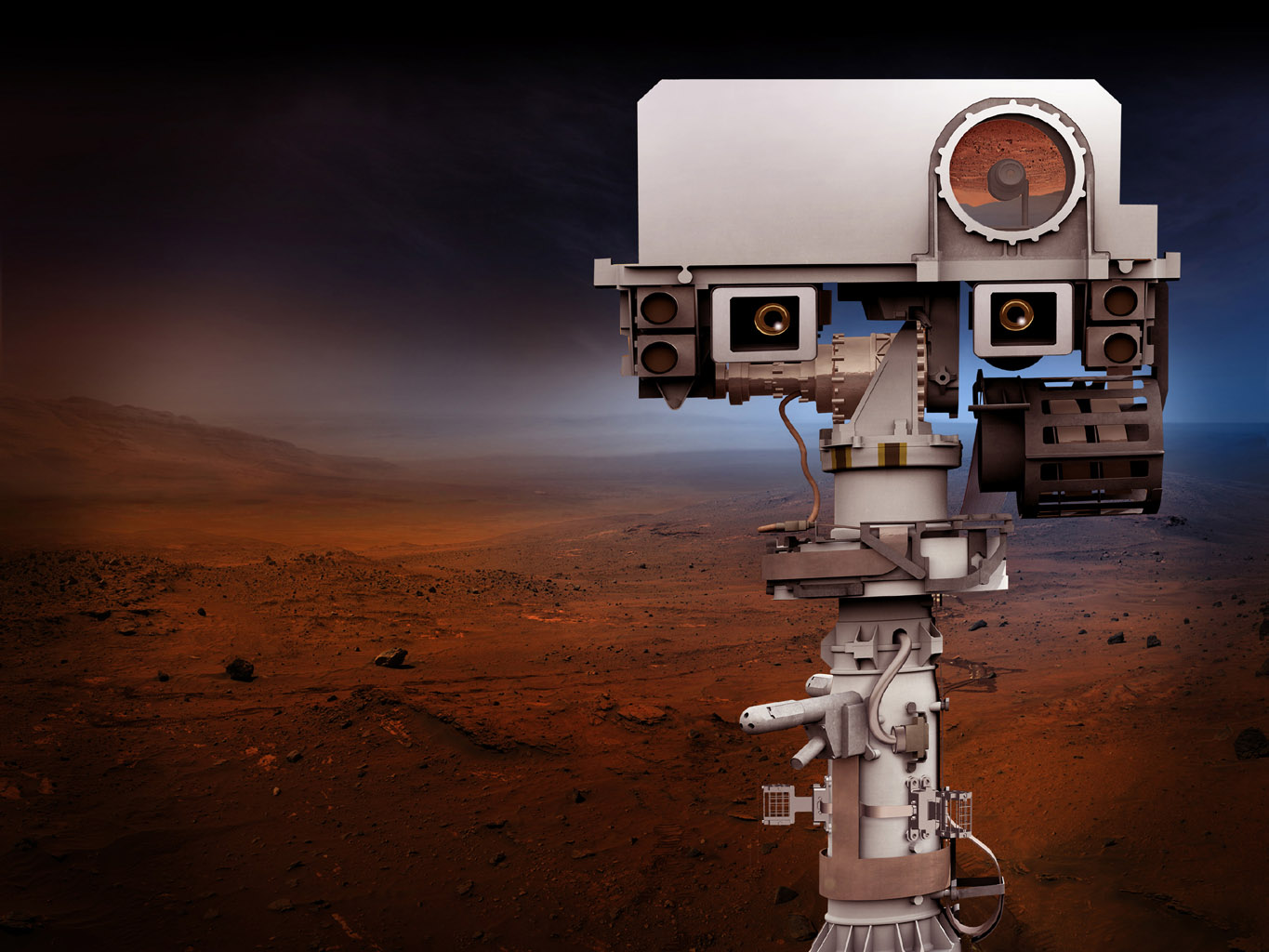

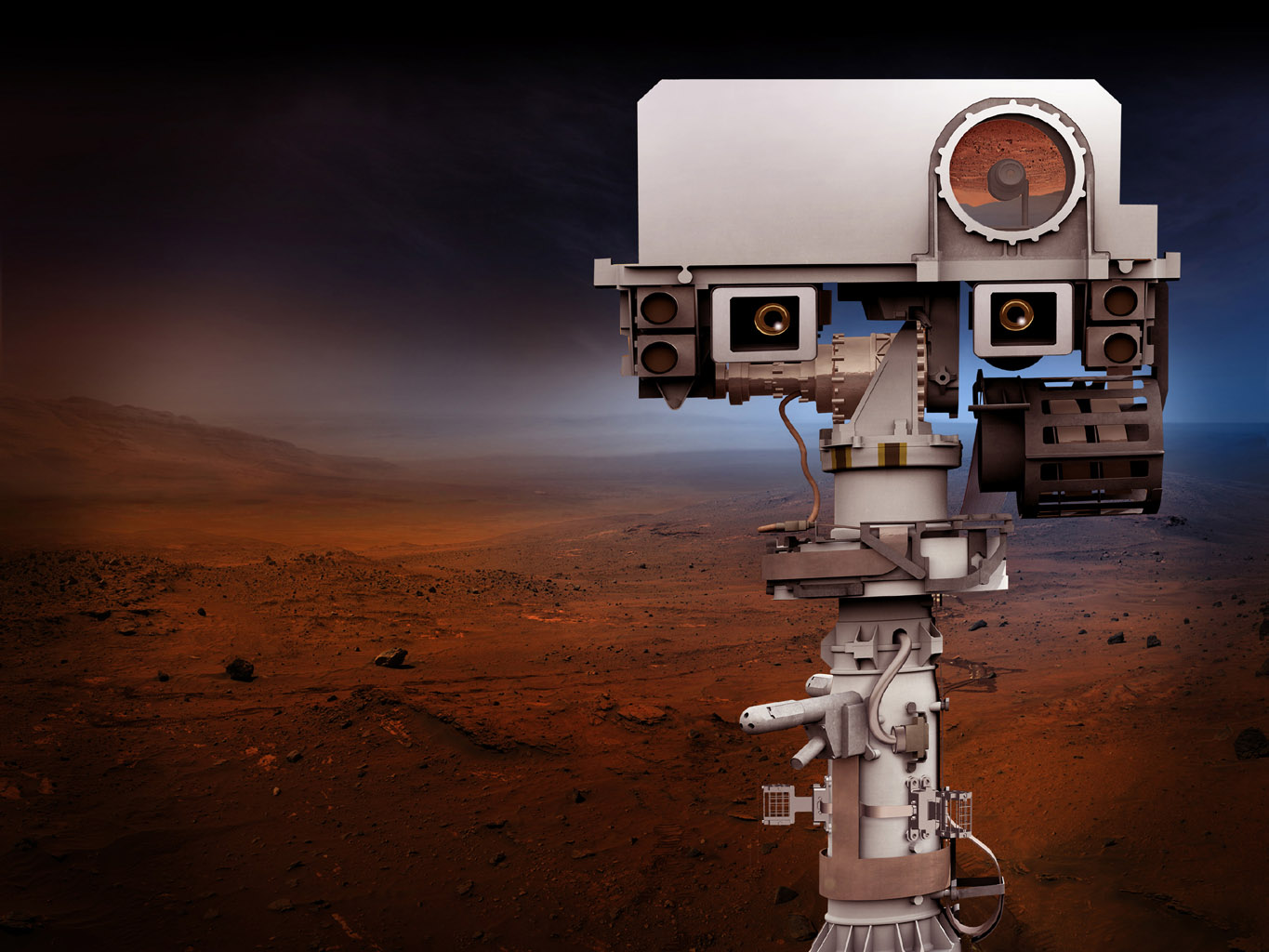

In less than three years, a robot larger than an SUV (that’s a pretty big space bot) is going to blast off from Earth and head towards Mars. The droid will gently parachute down onto the red planet’s surface, guided at the very end by a skycrane, which will bring it safely to the ground. That’s the plan anyway for Mars 2020. In addition to becoming the most modern piece of tech on our neighbor planet, the new robot will also have more cameras than any rover to go before it.

It’s 23 cameras will outnumber Curiosity’s collection by six, Spirit’s and Opportunity’s each by 13, and Sojourner’s—the first rover—by 20. The eye upgrades, facilitated by advances in camera engineering, will give researchers a clearer look at Mars, sure, but they will also help save time and ease the grueling process of scheduling tasks on Mars from 33.9 million miles away.

Currently, to plan out a day’s worth of work on Curiosity, it takes scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) about eight hours to first process information gathered by the rover the day before, plan out the next day’s tasks, engineer those projects, bundle them up in digital instructions, and send more instructions back to Mars.

Engineers spend about a half hour to an hour alone processing the images that Curiosity sends back, stitching together wide angle photos, or lining up stereo images that let humans—or rovers—deduce information about depth from two-dimensional pictures.

“For things like driving or operating the arm, we take a picture with the left camera and a picture with the right camera” Justin Maki, the imaging scientist for Mars 2020, says. “Then we match up pixels between the two images to create a 3D image of the terrain. Because we have these wider field of view lenses, we end up with better quality stereo terrain maps.”

Maki and his team’s plan for the next mission is to compress the entire daily timeline down to five hours, in part by taking advantage of the smaller, cheaper, and more powerful cameras on the rover, which have a much wider field of view.

The wider field of view and high resolution means less time stitching together or processing images, and more time working on the next day’s assignments for the rover, whether that’s telling it to drive over to a rock, avoid an obstacle, or fire a laser.

“The shorter the timeline the more chances you get for ground-in-the-loop planning,” Maki says. That means that there’s more room to accommodate the 40 minute delay in days between a day on Mars and a day on Earth. It may not seem like much, but the delay can periodically throw things out of whack when we’re talking interplanetary scales.

“Some days you come into work in the morning and the plan hasn’t finished executing yet on Mars,” Maki says. That’s a problem, because researchers have to wait for the info to come in to start their day. Delays—plus the eight hours needed to plan and program a day—mean sometimes unpredictable hours, which can get exhausting, especially when expeditions are extended and the team is five years into a two year mission, which is the case with Curiosity.

“When we first land we’ll work all through the night,” Maki says. “But that’s hard to sustain much beyond three months.”

A shorter, five hour window means that information can come in late to the JPL lab and researchers can still turn around precisely calibrated instructions by the end of a normal working day, which wouldn’t be possible without the wide-angle lenses on the camera taking precise pictures of the surrounding environment, samples, and the rover itself.

Of course, in addition to providing detailed navigation aids, the large number of cameras also means more amazing images for everyone back home as well. High-speed landing video cameras, along with a specialized microphone, will capture the harrowing descent of the rover to the surface. Yes, the engineers will see detailed footage of how the parachutes deploy in Mars’ atmosphere, but the rest of us will get a live-action remake of Seven Minutes of Terror—the immensely popular NASA animation of Curiousity’s landing.

And, like other NASA missions, when information comes back from Mars 2020 mission, the public will be able to follow along almost as soon as Maki and the other mission scientists get the information.

“It’s a really unique time in human history. Before, explorers would go off on a ship and hopefully they would come back with some stories or maybe some drawings,” Maki says. “But now anyone in the world can participate in our voyage in real time.”