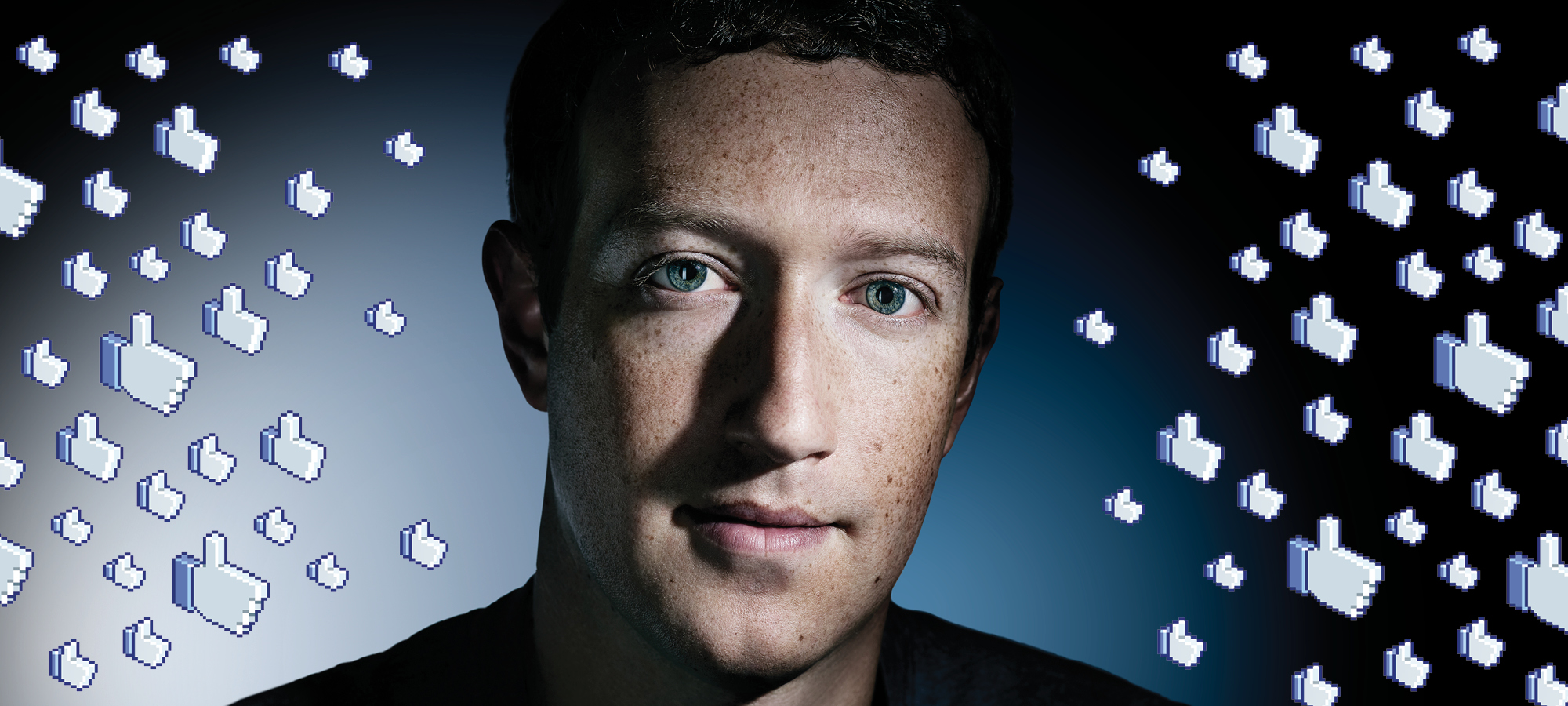

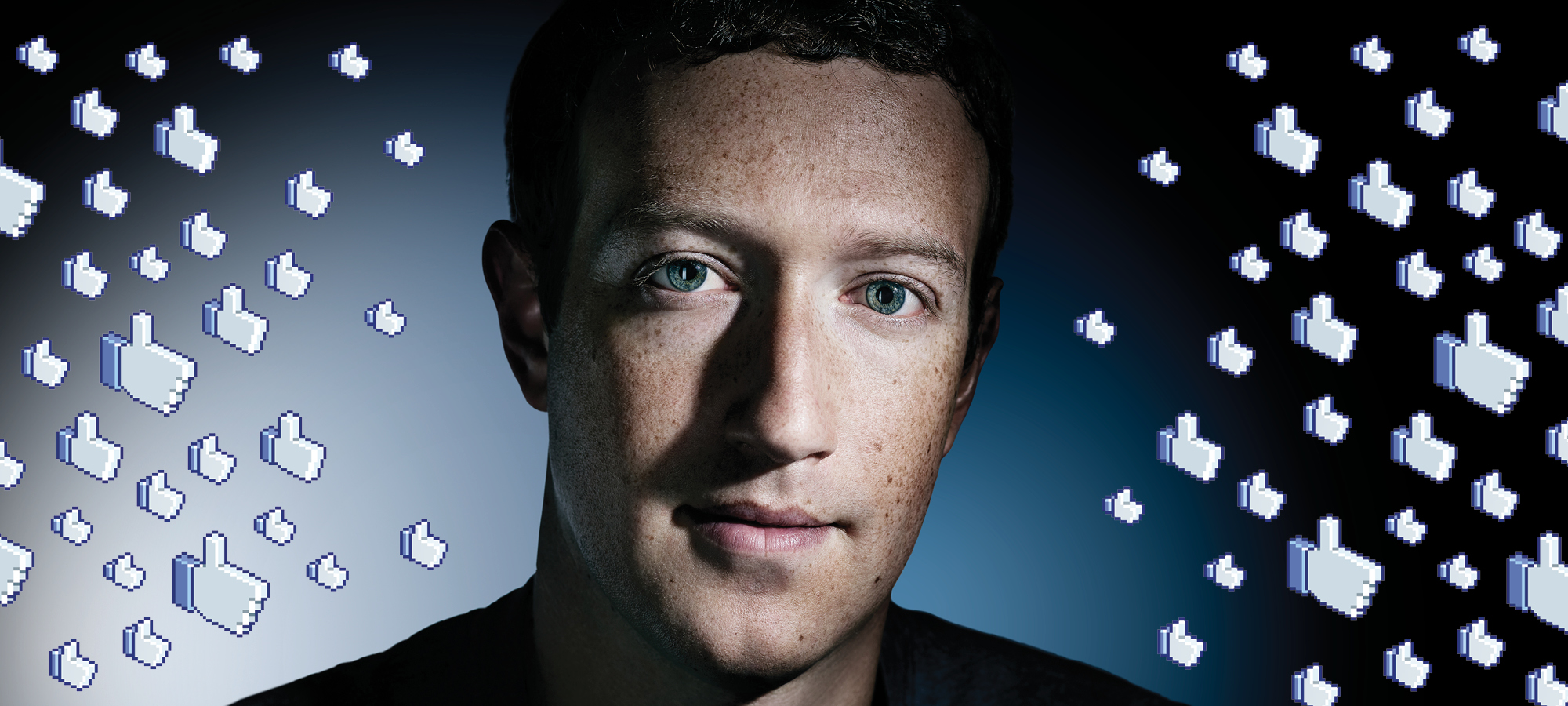

Photography by F. Scott Schafer

In just 12 years, the Facebook founder built an empire of 1.71 billion followers. His next goal: to friend the rest of humanity.

Down the hall from Mark Zuckerberg’s desk sits a virtual reality studio. Foreign heads of state and other dignitaries have been known to lose themselves here in games of zero-gravity Ping-Pong and the real-seeming experience of firing virtual fireworks at each other. Such are their number, and frequency, that on an early summer morning Zuckerberg is at a loss to remember—or perhaps too diplomatic to divulge—one of their names. He does, however, recall the anecdotal nugget of the man’s visit.

“He wouldn’t leave,” says Zuckerberg, sitting in a glass-walled conference room in Facebook’s cavernous and almost factorylike headquarters in Menlo Park, California. “His aide was like, ‘Mr. Prime Minister, you have to take off…you’re two hours late for your flight.’”

That is exactly the reaction that Zuckerberg—the 32-year-old, still jeans-and-tee-clad creator and CEO of Facebook—wants to elicit from millions of people he hopes will strap on his Oculus Rift headset. But there’s way more to it than a feeling of presence with Ping-Pong opponents. Zuckerberg wants Oculus, or some future iteration of it, to replace our laptops, our smartphones, our televisions, the art on our walls, and, in some cases, seeing our friends in the flesh. So instead of owning a bunch of devices, you will swipe your emails and favorite shows into virtual view and go at it. The point isn’t living in solitary work or game mode, but rather connecting even more frequently with people through a technology that tricks your mind into thinking it’s somewhere else, without actually having to be there. Or letting you hold and flip through digital files at your desk as if they were physical, with augmented reality. Having brought together 1.71 billion people on a social-media network that began just 12 years ago in his dorm room—a network that now comprises the largest global audience in human history—Zuckerberg wants all of us to start connecting in his new realities.

As he sees it, in just 10 years’ time, “VR will be a mainstream-computing platform.” And just as we saw an explosion of apps for our smartphones, an entire ecosystem of activities will be built up around it.

“You can bring these objects into any space,” he says. “I’ll be able to say, ‘OK, we’re here together, let’s play chess.’ Now here’s a chessboard, and we can be in any space. We can play chess on Mars.”

Zuckerberg’s long game isn’t the chessboard, or even building out a virtual Mars—though he plans on being a part of that too. His driving vision is to connect our entire planet. For that reason, he pushed Facebook to buy Oculus for $2 billion in 2014—when everyone else thought it was just another screen for gamers—seeing it as a means to socialize in immersive technicolor from across the world. For that reason too he’s working to beam the Internet, via DIY transmitters, or drones and lasers, to the billions on the planet who do not yet have online access. And in this larger pursuit of connecting people and technologies, he has pledged nearly the entirety of his fortune (99 percent of his Facebook shares, valued at some $45 billion) to his Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, named for him and his wife, Priscilla. Its stated goals are “advancing human potential and promoting equality.” And he plans to do that, in part, by improving education and trying to cure the world’s most intractable diseases—by giving scientists access to engineers, whose work could include artificial intelligence.

It’s safe to say that no one is doing more, in so many fields, to bring about this singular vision of connectivity. “I certainly would not underestimate him,” says Ben Horowitz, whose venture-capital firm, Andreessen Horowitz, is a Facebook investor. “He is totally determined, willing to fail and try again, has the resources, and he’s a genius. If he can’t lead the way, then I’m not sure who can.”

That was hardly Silicon Valley wisdom two years ago when Zuckerberg urged Facebook to purchase Oculus. “Everyone really scratched their heads and said: ‘VR, is that really a thing? And, Facebook? Why is Facebook doing it?’” says Mike Schroepfer, the company’s chief technology officer, referring to the idea of Facebook getting into the hardware business. At the time, Oculus didn’t have the necessary hand- and head-positional tracking that would make it feel immersive, or real to life. “It was sort of a one-demo thing,” says Schroepfer.

In the past two years, a number of important advances have occurred: higher-quality, pixel-dense LED screens; faster processors; and improved sensors. And during that same time, others have followed Zuckerberg’s lead. Google backed Magic Leap, an augmented-reality platform that overlays objects onto the real world. (It also rolled out the $15 Google Cardboard, which offers a VR experience via your smartphone.) Microsoft unveiled its HoloLens (also AR). And Apple is reportedly developing its own headset.

What Zuckerberg is proposing—and working to create—is a radical rethinking of our relationship with our personal technology, which he doesn’t see as all that personal right now. “It’s kind of crazy to me that we’re here in 2016 and the defining relationship we have with computers and phones is apps, not people,” he says. “It feels very unnatural and overly technical to me.” His goal is to help build out the next-generation computing platform, in which, he says, “people are the foundational element.”

His end goal is a seamless integration of our digital and analog lives: augmented reality, also known as mixed reality. Not a full virtual zone like in VR, but one based in the real world, in which you call up the things you need, and the people you need, when you need them. “If you look around the room,” he says, gesturing around the nearly empty conference room, “how many of the things here need to be physical?” It turns out, not much. Not the laptops on the tables, not the TV screens on the walls. “Instead of buying these things for hundreds of dollars,” he says, “you’d buy it for like a dollar in an app store and use it whenever.”

In addition to the social apps he expects to find in the virtual world (attending a lecture across the globe, for example, or standing inside a 360-degree live stream of a street protest in a foreign capital), Zuckerberg sees this technology usurping our solitary moments.

Instead of binging on eight hours of Netflix, with our brains in a zoned-out state, Zuckerberg sees some of us choosing the interactive brain-on experiences of AR and VR. “I think a lot of time people frame the question like this: ‘Is it weird that people will be spending time in something like VR when they could be interacting with people instead?’” says Zuckerberg, who notes that he has teams doing studies on the mental effects of VR exposure. “I think that misses the point on a couple of fronts, the main one being that what is actually being replaced are other modes of technology like TV, where I think we’re more passive. …You want to be in a personalized experience where you’re making decisions. You want to be interacting with other people. And VR is a natural extension of that.” So in Zuckerberg’s augmented future, we all become more social, not less.

On the surface, it’s easy to dismiss Zuckerberg’s efforts to connect the planet as solely self-interested. After all, Facebook is a public company that makes money by selling ads against its user. And his Internet-access program called Free Basics, which makes a limited portion of the Web available for free, has been accused of a Facebook bias. When India rejected it in February, the criticism centered on Facebook acting as gatekeeper, deciding what would and would not be accessible.

Yet Zuckerberg argues the Internet has the power to lift people out of poverty and promote education, which explains why he’s made connectivity the cornerstone of his $350 billion company. As Horowitz puts it: “Mark has a mission much larger than himself, and he won’t stop until he achieves it.” Within Facebook, large swaths of resources tackle complex tasks like automatic language translation. That way, people can eventually communicate with nearly all of humanity, with fewer barriers to understanding.

While India was a major setback— “There are a billion people in India who are not on the Internet, so that’s a big one,” Zuckerberg says—he has a track record of proving naysayers wrong. Today, Facebook has launched Free Basics in 42 countries, bringing 25 million people online for the first time.

Zuckerberg slots the unconnected of the world into three categories: 1 billion who can’t afford the Internet, 1 billion without access because they are out of reach of Wi-Fi, and 2 billion who don’t know why they would want or need to buy a data plan in the first place.

For the billion who want it but can’t afford it, Facebook is designing plans for cheaper infrastructure, and aiming to cut the costs for the telecommunication companies. In July, Facebook introduced another hardware product to improve connectivity in rural areas: OpenCellular, a shoebox-size transmitter that’s attachable to existing infrastructure and can broadcast 2G to LTE cellular service as well as Wi-Fi, and can support up to 1,500 users within 6 miles. Facebook is making the schematics free, encouraging telecom companies or entrepreneurs to build wireless infrastructure off the OpenCellular platform.

For people in remote areas, Facebook is planning to launch drones to transmit Internet from the sky. Named Aquila, the drone has the wingspan of a Boeing 737—113 feet—but weighs just 880 pounds and consumes the wattage of a large microwave. It’s essentially one big wing, laden with Internet-beaming lasers. These drones might eventually stay aloft three months at a time, using solar power and gravitational energy. On its inaugural test flight, the drone stayed airborne for 96 minutes—three times longer than planned—before being grounded due to a structural failure. Aquila’s lasers will send signals to towers and dishes over a 31-mile radius, delivering enough bandwidth to support thousands of users.

The last 2 billion, those unconvinced of the Internet’s purpose, are the most difficult. Zuckerberg puts it like this: “You’ve never used the Internet, and someone comes up to you and asks, ‘Do you want to buy a data plan?’ You’re like, ‘Why?’”

Why indeed, if you’ve never sent an email? The commitment is enormous, and the venture is full of prickly political and cultural issues, as the India blowback showed. Yet this goal is crucial to Zuckerberg’s belief that the Internet makes the world a better place. “If we are trying to give every person the power to share and connect to everyone,” he says, “then it’s hard to do that when more than half the people are not on the Internet.”

Others too want to see this happen. Elon Musk and SpaceX are taking this on via Internet-beaming satellites, as is Facebook’s fiercest competitor, Google, with its inflatable balloons and drones. So why should Zuckerberg be the one to succeed? “I think anyone could do it,” he says sincerely. “But I think often the question is, ‘Who cares the most to get it done?’”

In 2015, when Zuckerberg and Chan’s daughter, Max, was born, Zuckerberg wrote an open letter to her, pledging to commit—within their lifetimes— 99 percent of their wealth to education reform and fighting disease, among other things.

Zuckerberg has long cared about education. In 2010 he donated $100 million to the Newark, New Jersey, school system—a venture that left him frustrated due to the bureaucracy and politics. This time around, he’s focusing on reforming education with something he understands: software.

In January 2014, Zuckerberg toured a school in Sunnyvale, California, which is part of Summit Public Schools, a charter-school system started by a software engineer. The classrooms were set up like a startup, with no walls between them, and computers on every shared table. Most compelling to Zuckerberg, though, was that they were experimenting with personalized education. Each student learned at his or her own pace. Groups worked together on more complex problems. Zuckerberg asked the program’s founder to meet the school’s engineering team that had built the initial personalized education platform. “Her response was, ‘Yeah I’ll introduce you to him,’” Zuckerberg said.

Zuckerberg, surprised that the “team” was a single person, made her a deal. He’d give her more engineers (which will number 30 from his own troops by the end of the year) as long as the software remained free for other schools to use, thus connecting educators and propagating knowledge. She accepted. This school year, about 120 schools will use the personalized education software. In the next decade or so, Zuckerberg hopes to get half the country on board.

To Zuckerberg, education is just another engineering problem. So is medical research. So is anything. That’s the heart of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative as it progresses: the idea that engineers can scale progress in any field. A researcher studying cross sections of the brain to understand neuron pathways, or to look at the growth of cancer cells, could take years, and even a lifetime, of physical scanning and study. But applying AI (and its ability to sort information exponentially faster than humans) to this process could reduce that time by orders of magnitude. “If top scientists had the firepower of a world-class engineering organization behind them,” says Zuckerberg, “I’m pretty optimistic we could help build some tools that can unlock a lot of new understanding.”

Not one to lack vision, he’s willing to go so far as to say that science can, through AI and machine learning, one day manage or cure the main diseases that kill humans, such as cancer. “I really want to convince the world that it is possible,” says Zuckerberg, “to get to a place where we can manage all diseases by the end of the century. I believe that we can.”

And no one has yet gone wrong betting with him.

This article was originally published in the September/October 2016 issue of Popular Science, under the title “The Most Social Man On The Planet.”