Crunchy or smooth peanut butter. Toilet paper tucked over or under. Clicky top or cap pens. Jellies or sponges. No, not the kitchen items—the animals. Maybe you haven’t been debating that last issue with the same passion as the eternal toilet paper question, but evolutionary biologists have. Now one group says they’ve got an answer: it’s the jellies.

The question isn’t whether jellies or sponges are better (it’s obviously sponges, because they have no real circulatory, digestive, excretory, or respiratory systems yet still manage to survive—plus you can use ’em to wash your armpits). The question is which lineage came first. Or rather, which evolved first.

You’ve probably seen a basic tree of life—more accurately called a phylogenetic tree—that shows when different types of plants, animals, and microorganisms evolved over the millennia, and therefore how closely they’re related to one another. You may have also assumed that you were looking at the final draft. But for lots of creatures, that’s not the case at all. Historically, biologists based their trees on which animals seemed the most closely related based on physical features and pieced that together with fossil records to estimate when and how the various branches on the tree formed.

Today, we can look to genetics for better answers. It’s easier to tell how related two animals are from their DNA code than from their appearance because, quite simply, DNA is where evolution happens. Random mutations arise there, particular genes are selected for, and as the genetic code changes, so do the animals. Genetic analysis has helped biologists settle lots of debates. But some of them are complicated enough to drag on for a spell.

That’s why biologists and geneticists from Vanderbilt University and University of Wisconsin-Madison teamed up to resolve some of the more contentious issues. They published their findings on Monday in Nature Ecology & Evolution. In many cases, they found that the debate really came down to one or two genes, which means whenever previous studies had failed to consider those genes, they were coming up with flawed results based on the scientists’ own biases. Much of your outcome depends on what data you choose to include or exclude. And if removing a single gene from the analysis could flip the result, the biologists in the new study concluded, the issue was simply too close to call.

And as a very important sidenote: this almost certainly isn’t the final call on this debate. Evolutionary biologists have been discussing it for decades. Heck, a study came out just last month arguing exactly the opposite, and the scientific community will probably publish many more opposing papers in the years to come. This is just one solution to the very complicated, bias-prone world of phylogenetics. In the view of the scientists behind the latest paper, the jellies vs. sponges case was close enough to call—so they’re calling it.

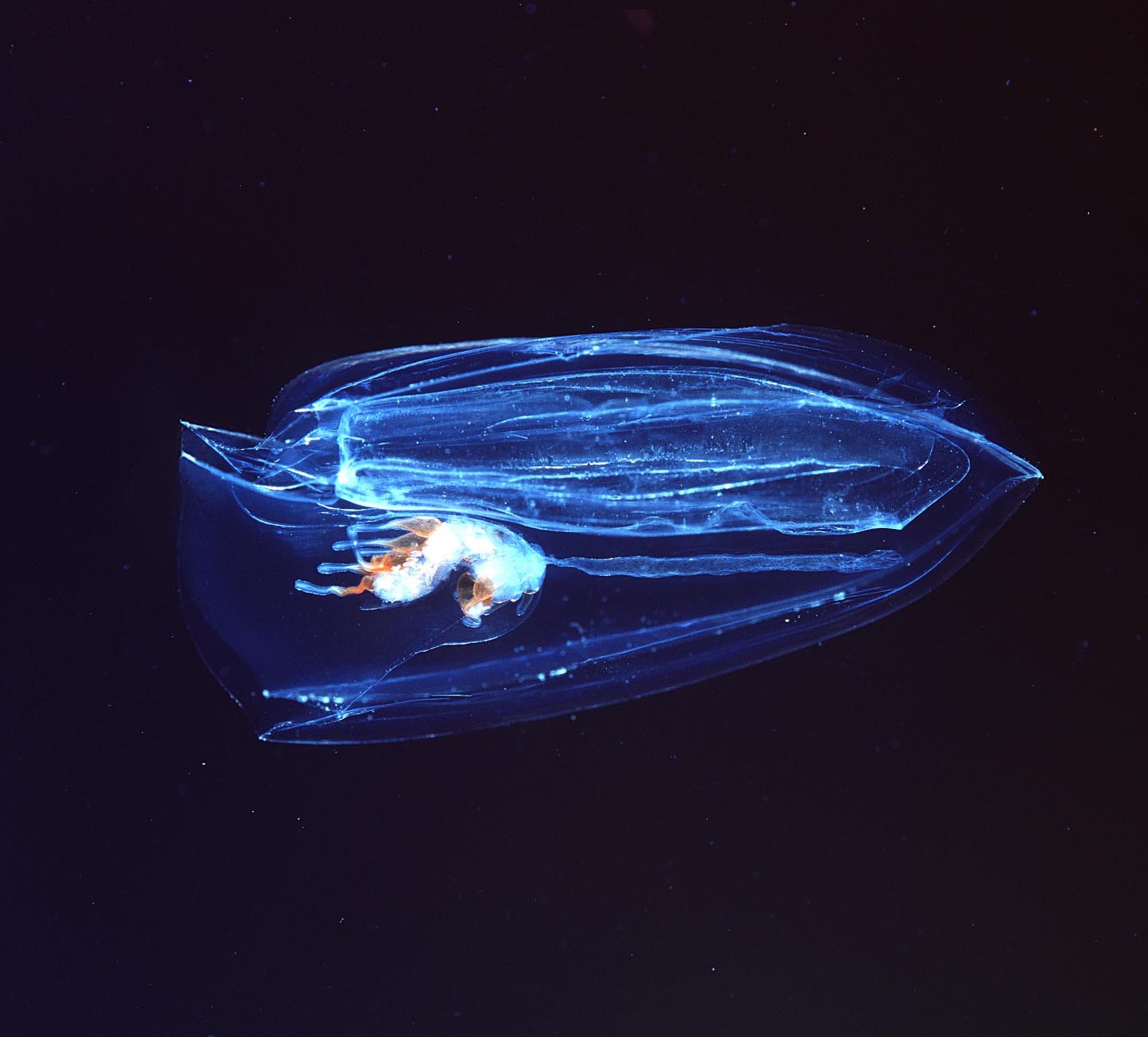

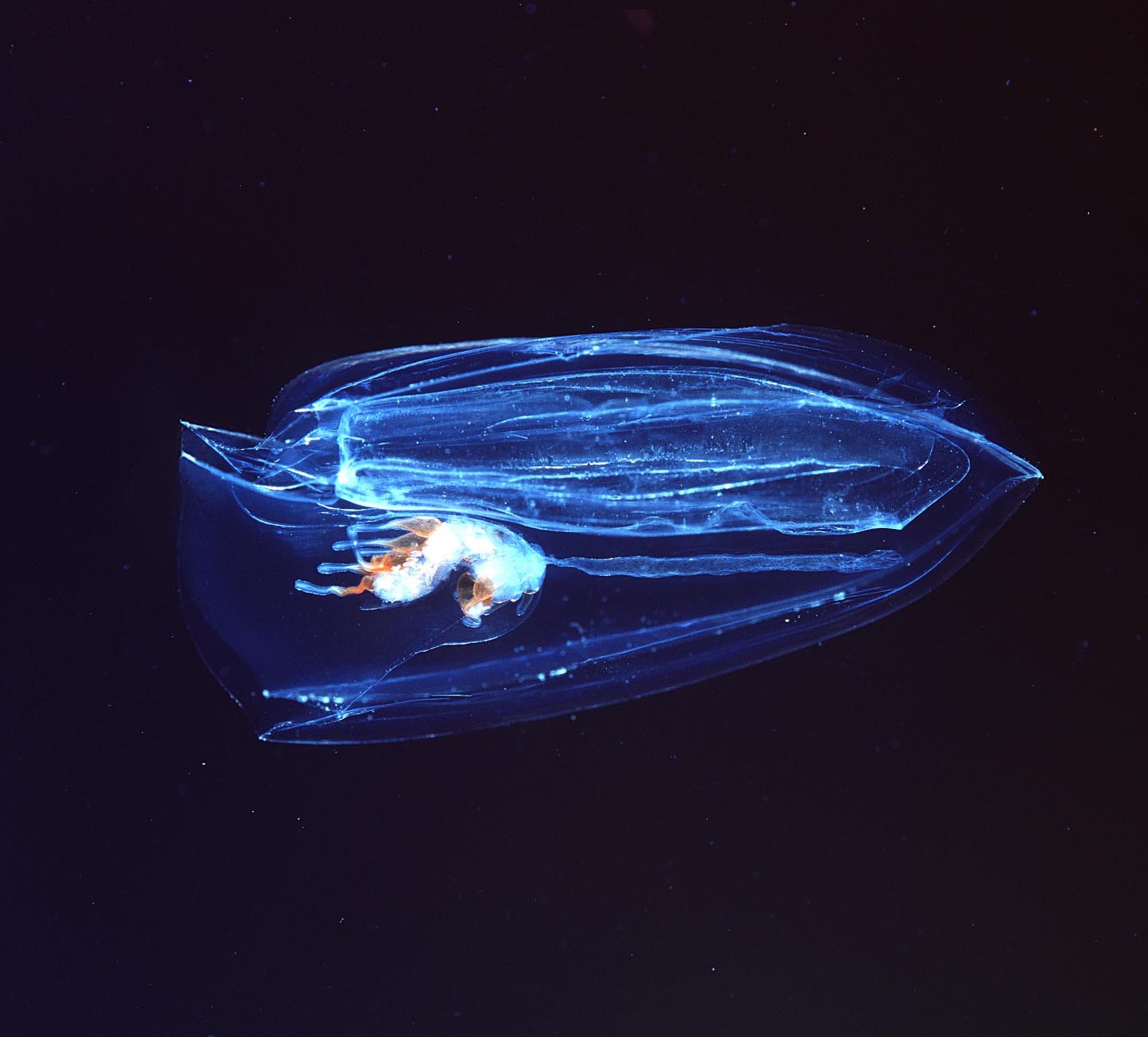

In looking at the genes connecting marine jellies (ctenophora), sponges (porifera), and the group of all other animals (yes, it’s a giant group), they found most of the key genetic relationships supported a closer link between sponges and the ‘everything else’ group than between marine jellies and everything else. That makes jellies the outlier. And in a phylogenetic tree, the outlier is the early-comer. As the animal kingdom evolved from a common ancestor, ctenophora branched off to do its own thing first, then later sponges branched off from the remaining group.

All this means that even though jellies have rudimentary nervous and digestive systems that sponges lack, we’re more closely related to those squishy tubes that stick to rocks and feed by flushing water through their combination mouth-anuses. Happy Monday!