Whether you’ve been chased by a goose or witnessed an ostrich run at top speed, you know birds can sometimes be terrifying. At the top of the list is the cassowary—a demon bird that clocks in between 4 and 5.6 feet tall. It can run up to 31 miles per hour on its powerful legs, each tipped with three dagger-like toes, and can leap almost 7 feet up in the air.

The three modern species of cassowaries reside on various Pacific islands, including New Guinea, where they’re prized for their meat, feathers, and bones. But how did ancient communities ever wrangle the fierce animals?

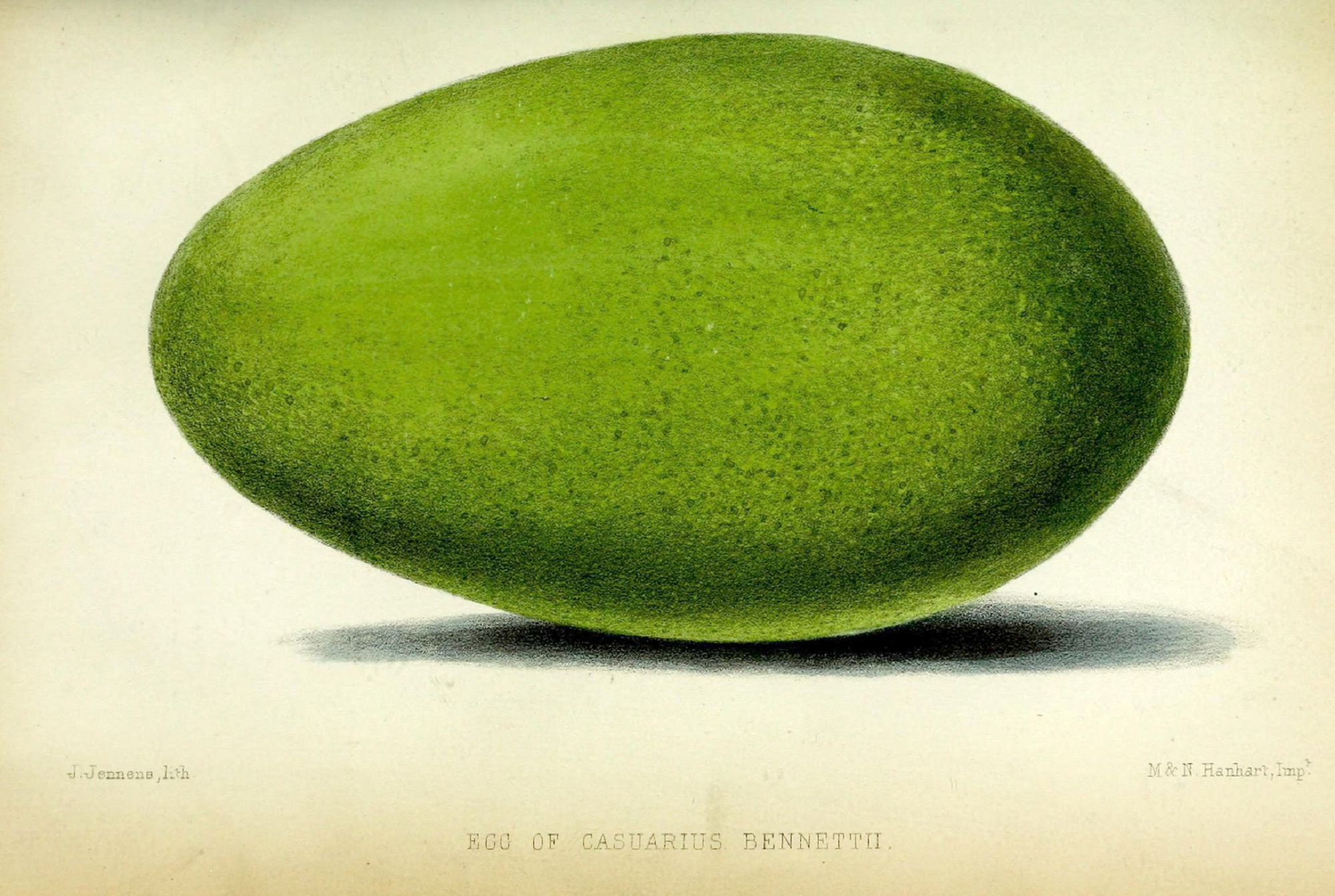

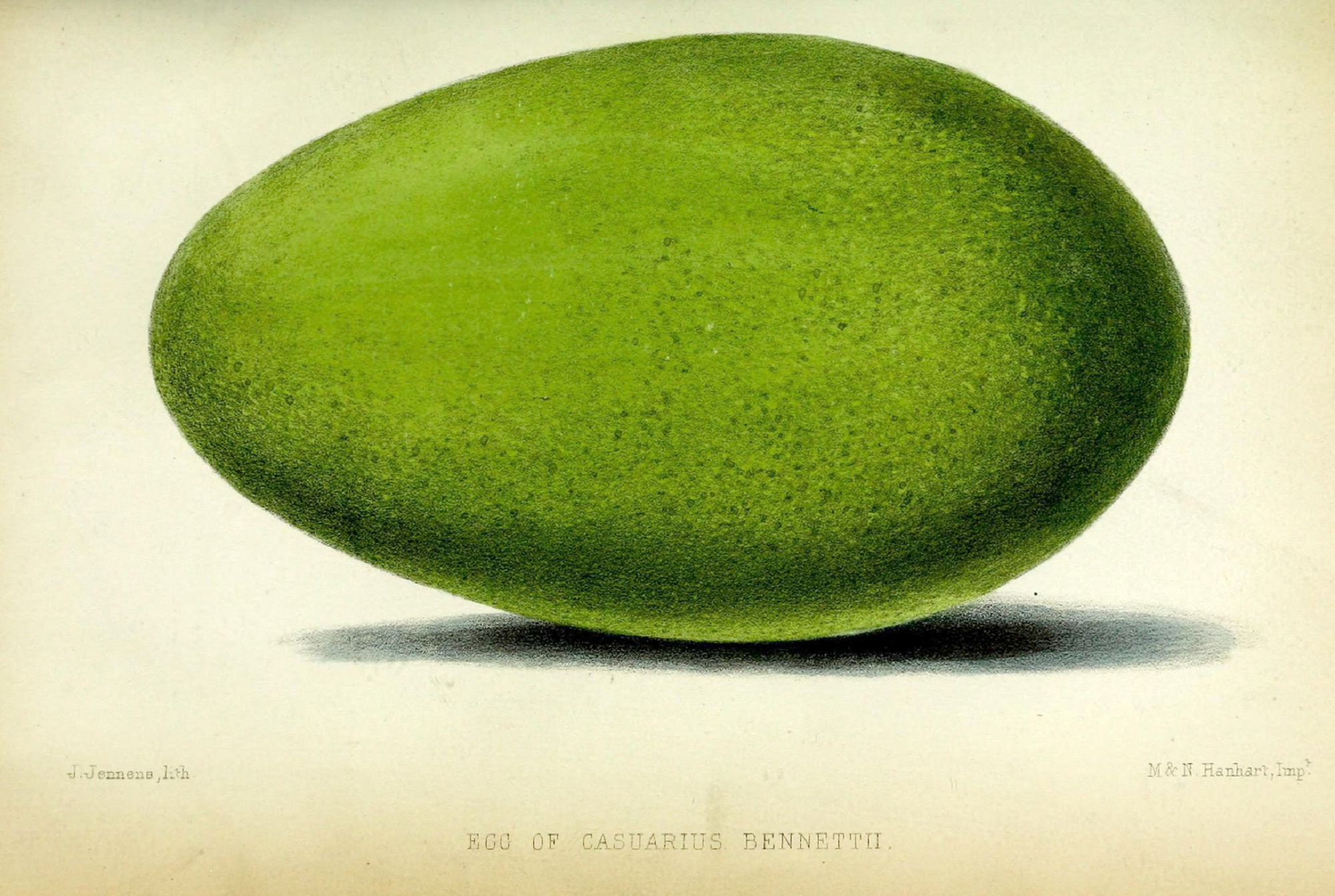

Turns out, they may have brought them home with them. There are clues that as early as 18,000 years ago, humans in New Guinea were systematically harvesting cassowary eggs, new research shows. The paper, published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, details how a team of anthropologists from the US, Australia, and New Zealand used ancient eggshell fragments found at rock shelters and a combination of 3D imaging, modeling, and morphological descriptions to determine how old this practice was.

[Related: New Guinean singing dogs still roam the wilderness]

“The eggs were harvested very late in the developmental window of cassowary chicks,” says Penn State archaeologist Kristina Douglass, the study’s lead author. “The pattern that we found is not a random pattern—people were intentionally selecting them at that stage.”

There’s two hypotheses why: Collectors may have immediately consumed the contents of the egg, as evidenced by cooking burns on the shells, or they may have tried to hatch and rear these chicks themselves. Cassowaries are dangerous and difficult to hunt, and given that their chicks identify the first being they see as their parent (a process called imprinting), it’s much easier and safer to try to raise them in captivity.

While it was probably wise that people didn’t take cassowaries head on, they didn’t domesticate them either. Douglass says that domestication entails human intervention for a species’ survival. Instead, she describes the egg-harvesting system as a possible form of management, where island dwellers bred the birds for their own purposes. This meant they may have been raising some cassowary chicks—even as many of the birds roamed free in the wild—and weren’t training the captive animals to depend on people.

Analyzing eggshells is cool, but to Douglass, what’s more interesting is that a pre-agricultural society had developed this practice of systematically harvesting and breeding chicks. “People who live off of the land have really sophisticated knowledge of that land,” she says. “We tend to think that it’s only when agriculture or industrialization developed that humans become savvy and civilized. All of those words are really loaded.” Calling hunter-gatherers and foragers primitive underestimates their level of knowledge.

[Related: Ancient hunter-gatherers didn’t all eat paleo]

Douglass and her team will continue to search for and analyze eggshells from all regions of New Guinea. The ecologically diverse island could yield different patterns at highlands zones versus at lowlands, potentially because cassowary development varied depending on region.

While cassowaries are still culturally important throughout New Guinea, Douglass says there’s no way to trace back one present-day group of people to the eggshells she analyzed because there have been so many migrations to and from the island in the past 18,000 years. Even so, it’s clear that this fierce creature’s esteem has persisted for millennia, rightfully earning it the title of “the world’s most dangerous bird.”